The Big Question: Is Cyprus on the brink of bridging Europe's last great political divide?

Why are we asking this now?

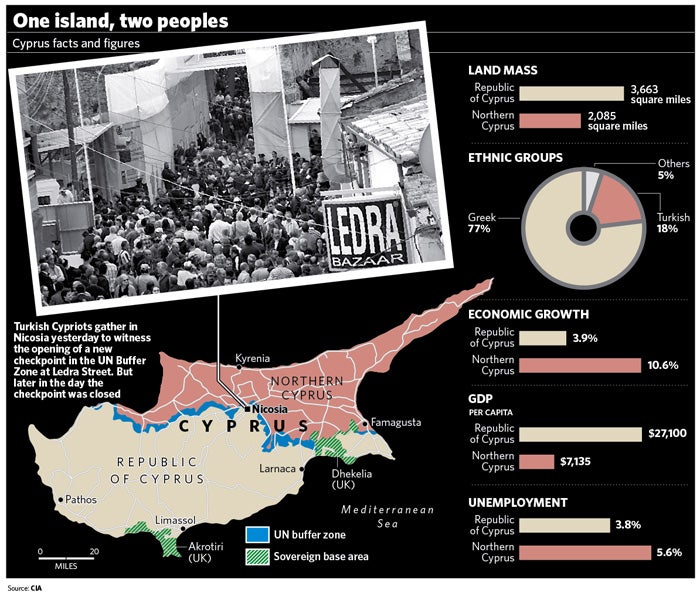

In a highly symbolic gesture, barricades that have divided Ledra Street – a shopping street in Nicosia – between Greek and Turkish communities in Cyprus for nearly 50 years, were removed yesterday, only to be closed again a few hours later following a dispute over policing.

Who removed the barricades?

Members of both communities, with the warm support of the European Union and the United Nations. So for a brief moment at least, everybody was singing from the same hymn sheet.

Haven't we been here before?

We have: back in 2004 hopes were high that the magic of EU accession would do its work and the two communities would enter the European Union as members of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation – the solution first agreed upon back in the 1970s. But it all went horribly wrong. Turkish Cypriots, who had long demanded secession to Turkey, voted for unification, but the Greek Cypriots, whose community has long advocated reunification, went the other way. Because the Greeks constitute an overwhelming majority (about 77 per cent) they had their way and Cyprus entered the EU as a divided island – an embarrassment both to Brussels and the UN.

What has happened since 2004 to change people's minds?

Large amounts of international pressure on the Greek Cypriot side, for one thing; the EU having found itself stuck with a highly unsatisfactory new member. By acceding to the EU with its divisions intact, the island's Greek Cypriot government obtained a veto over Turkey's relations with Europe. The island's unresolved status also complicated other issues – from co-operation with Nato in Afghanistan to Chinese shoe imports.

Outside pressure aside, the Greek Cypriot community has begun to realise that the status quo that works so much in their favour may not last. In the absence of a mutually agreed settlement – largely along the lines of the 9,500-page epic drafted by the UN under Kofi Annan – the island could move to formal and permanent partition, leading to the permanent loss of land that Greek Cypriots claim as theirs, the possible acceleration of a building boom on that land, and the arrival of more Turkish settlers. So in February they elected the communist Demetris Christofias as president, with a mandate for change.

Isn't this all Britain's fault?

Britain obtained a lease on this highly strategic foothold in the eastern Mediterranean in 1878, as a reward from the crumbling Ottoman Empire for supporting it in its war against Russia. When the empire entered the First World War on the side of the Central Powers, Britain annexed Cyprus and held it until 1960.

Independence came after a military campaign by the Greek Cypriot nationalist organisation EOKA, but the complex agreement depended on guarantees from both Greece and Turkey as well as the UK, which retained military bases in the island. It was never going to be a recipe for harmony and, sure enough, disputes erupted almost at once, leading to intercommunal violence across the island in 1963 and the dispatching of a UN peacekeeping force – still there today – the following year.

So when did the Turkish Cypriots get their own statelet?

That happened in 1983. Cyprus's basic problem is that many people on both sides feel much more allegiance to their "motherland" than to the island itself – the Cypriot sense of identity is chronically weak and the urge to secede to one "motherland" or the other keeps re-surfacing. In 1974 right-wing Greek nationalists who favoured the island's union with Greece fomented a coup, which failed in its aim but succeeded in provoking Turkey into a full-scale air and sea invasion. The attack led to the administrative division of the island between the two sides and the eviction of more than 200,000 people from their homes.

The island has lived in the shadow of those events ever since. In 1983, Turkish Cypriots cemented the invasion by declaring their part of the island the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. But the United Nations said the new state was illegal, and Turkey remains the only state to recognise it.

What happened after that?

The two states settled down uneasily to pursue their separate destinies. The Greek south enjoyed a long-running tourist boom, which has made many people very rich but which has also resulted in the blighting of the island's beauty by hundreds of thousands of holiday chalets, and the despoliation of the coast by ribbon hotel development.

The Turkish side has failed to match the economic growth of the south and is still heavily dependent on subsidies from Ankara. One central reason for the shifting of Turkish Cypriot views over reunification is because they see how their Greek neighbours have profited from the rape of their side of the island, and are impatient to begin doing likewise.

If you want to see how one of the last corners of Mediterranean wilderness looks, now is your chance, before a final settlement is reached and the bulldozers get to work on the north side of the island, too.

So when will the two sides begin talking again?

At a meeting in Nicosia two weeks ago, the UN representative Michael Moller said they would begin in three months. The two sides have already agreed to set up committees and working groups to prepare for them. But, given the calamitous failure of Mr Annan's initiative in 2004, no-one is making rash predictions just yet.

Could there be any other victims of a settlement to the dispute?

There certainly could be – and quite a lot of them British. Our troops have carried out the lion's share of UN duties since the 1974 invasion, and pretty cushy duties they have been – in an agreeable climate with cheap beer and friendly girls.

Meanwhile, the failure of Turkish Cyprus to secure friends other than Ankara has not deterred thousands of British sun-seekers from sinking their savings in northern Turkish properties, some of which could look decidedly perilous if an island-wide settlement of property claims is part of a final settlement.

So can the two sides look forward to a shared future?

Yes...

*The Greek Cypriot President Demetris Christofias has the authority to keep his community behind unification

*Greek Cypriots could be ready to give up their commitment to a centralised state solution

*Turkish Cypriots extended a welcome to Greek Cypriots on Ledra Street yesterday – a sign of things to come

No...

*Enmity between the two communities goes back a very long way, and suspicion could rise to the surface again

*Both sides have reason to believe that permanent partition is the safer option for the future of the island

*The EU and the UN risk acting with insufficient energy and imagination to keep negotiations on track

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies