The Big Question: Why is tension rising in Turkey, and is the country turning Islamist?

Why are we asking this now?

For Turkey's more radical secularists, there is a war going on between the defenders of Kemalism – the mix of authoritarian secularism, statism and nationalism that is still Turkey's official ideology – and a government intent on imposing Islam on the country. The AKP government insists the struggle is between democrats and defenders of an outdated authoritarian political vision. Cynics see a battle between two sides linked by their obsession with controlling the state apparatus and their cavalier attitude to democracy.

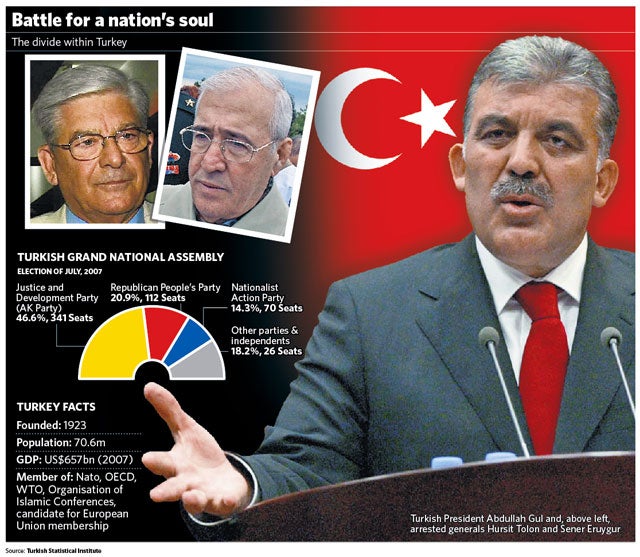

Since March, eight months after it swept to victory at general elections with 47 per cent of the vote, AKP has been facing closure on charges of anti-secular activities. The prosecutor who opened the case called for five-year political bans for 71 AKP members including the prime minister and the president.

Tensions soared again last week when police – for the first time in Turkey's history – arrested two retired top generals suspected of planning a coup attempt just two hours before the prosecutor pleaded for AKP's closure in court. Secularists insist the arrests were the AKP's revenge for the closure case.

What are the generals accused of?

Turkish newspapers said yesterday that the two generals will be charged with "leading an armed gang." For months, Turkey's press has reported that the 60-odd people in custody were planning a series of assassinations to destabilise society and force military intervention. One of the generals, however, is implicated in a different affair – two aborted coup attempts against the AKP in 2003 and 2004. The trigger for the plots was the Cyprus issue, not AKP's alleged threat to secularism. Many in the state apparatus saw the government's support for a UN-sponsored plan to reunite the divided Mediterranean island as a betrayal of Turkey's strategic interests.

Why do secularism and the military go hand-in-hand?

A soldier himself, Turkey's founder Kemal Ataturk repeatedly warned that "politics and soldiering have no place together." His secularist descendants ignored him, increasingly turning to the army to make up for their weakness at the polling booth. And the army, after each of the three coups and new constitutions Turkey has lived through since 1960, has more and more firmly cemented its position at the heart of the country's politics. Today, it has a constitutional duty to protect the Republic and its values. That doesn't just mean secularism. The enemy No.1 has changed over the years. It was leftists in the 1970s, and Kurds – a threat to Turkey's "indivisible unity" – in the 1980s and 1990s. Political Islam only topped the danger list in the mid-1990s.

So is Turkey really turning Islamist?

In power since 2002, AKP spent its first three years pushing through some of the most radical reforms in Turkey's history, including a rewriting of the Civil Code that won the plaudits of many secular-minded feminists.

Since 2004, though, reforms have ground to a halt. Reformist rhetoric has increasingly given way to authoritarian talk about "the will of the people" typical of right-wing Turkish parties drunk on power. AKP continues to insist it supports rights for all. But its ill-conceived efforts this February to end a headscarf ban in universities made it clear it saw some rights as more important than others.

What other signs of secularist fear is there?

Secularists' fears tend to crystalise around what they see as AKP's efforts to cram the state with its appointees. They are undoubtedly right. Secular-minded newspapers, meanwhile, are full of stories about efforts to ban alcohol on TV, force bars beyond city limits, and impose a conservative morality on the country. (Prime Minister Erdogan raised a stink recently, for example, when he called on all women to have "at least three children.") Above all, there is the widespread conviction – not backed up by most surveys – that more women are wearing headscarves than in the past.

So what does Erdogan represent?

The former dauphin of an Islamist politician whose career was ended in 1997, Erdogan grew up steeped in the Islamist counter-culture of the 1970s and 80s: anti-democratic and anti-western. Since his break with Necmettin Erbakan late in the 90s, though, he has changed tack radically. A mishmash of former Islamists, traditional right-wingers and nationalists, the party he formed in 2001 has espoused pro-European, pro-western policies since the outset.

While his enthusiasm for the EU seems to have waned since 2004 – in large part because of the sometimes hypocritical stance of anti-Turks in Europe – he is still Turkey's most pro-European politician of any stature.

Who does the West see as the good guys?

Unsurprisingly, western politicians tend to incline towards the AKP. But they sometimes go too far. Earlier this year, the European commissioner for enlargement opined that the struggle in Turkey was between "authoritarian secularists" and "democratic Muslims." This is naive, although understandable from a politician who appears to use Orhan Pamuk's novel Snow as a political Baedekers.

AKP may be more approachable than the secularist opposition, but all parties in Turkey eat at the same authoritarian trough. There's no clearer symbol of that than a party law which permits leaders to act like petty despots. Apparently at the request of the Chief-of-Staff, Erdogan last year got rid of nearly half the MPs in his former government without even asking his closest advisers.

Where does Turkey go from here?

Analysts see three possible outcomes from today's crisis. The least likely is that Turkey reverts to full-on authoritarianism. Much more likely is that an uneasy truce will be signed between AKP and the state, almost certainly putting an end to hopes of reform in the near future. Liberals, meanwhile, hope AKP will realise that the freedoms it wants can only be guaranteed if it guarantees freedoms it doesn't want.

What Turkey needs, they argue, is a new democratic constitution to replace the one imposed on the Turkish people after the last military coup, and an end to a legal system which puts defending the state above defending the rights of its citizens. The chances of that are slim. In today's polarised atmosphere, it is difficult to see how anybody can create the consensus needed to rewrite Turkish politics completely.

Is Turkey's secularism under threat?

Yes...

* Turkey's secularism has weak roots, "like an odourless lily floating on water", to paraphrase the philosopher Ahmet Arslan

* Erdogan appears not to have understood what secularism is about, repeatedly insisting it is for states, not individuals

* Secular Turkey has long forced Sunni Islam upon all citizens, via the school curriculum and the state body for religion

No...

* Barely 10 per cent of Turks support Islamic law, and that number is decreasing

* Most Turks voted for AKP because it promised prosperity – if it fails to deliver they will kick it out

* With trade booming, Turkey's conservative heartlands are closer to the West than ever before

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments