Fake antiquities flood out of Syria as smugglers fail to steal masterpieces amid the chaos of war

In the first of a four-part series from Damascus, Patrick Cockburn finds that while much of Syria’s cultural heritage has been saved from being destroyed by Isis, workshops are taking advantage of the civil war to turn out imitations that are sold to the West

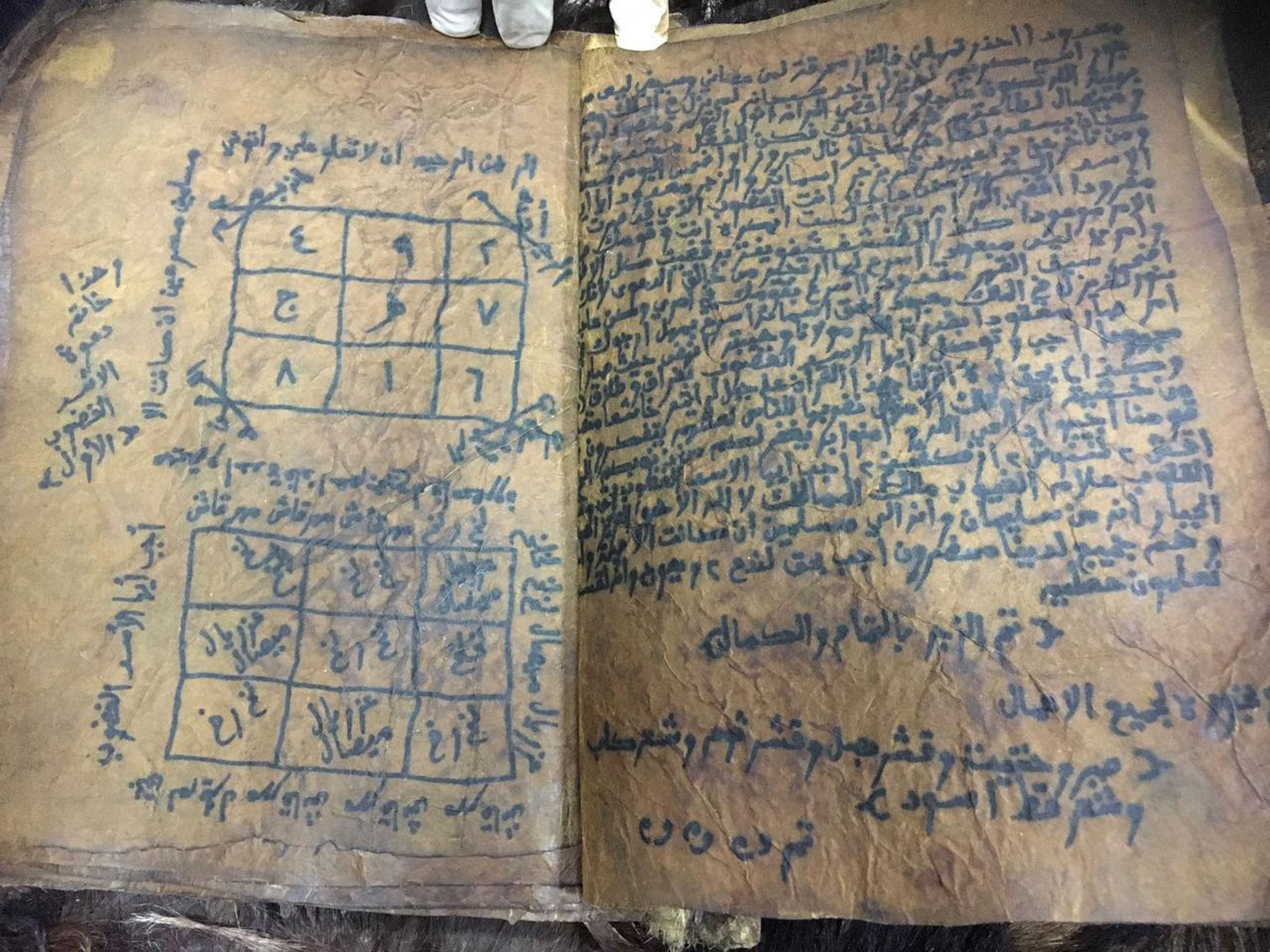

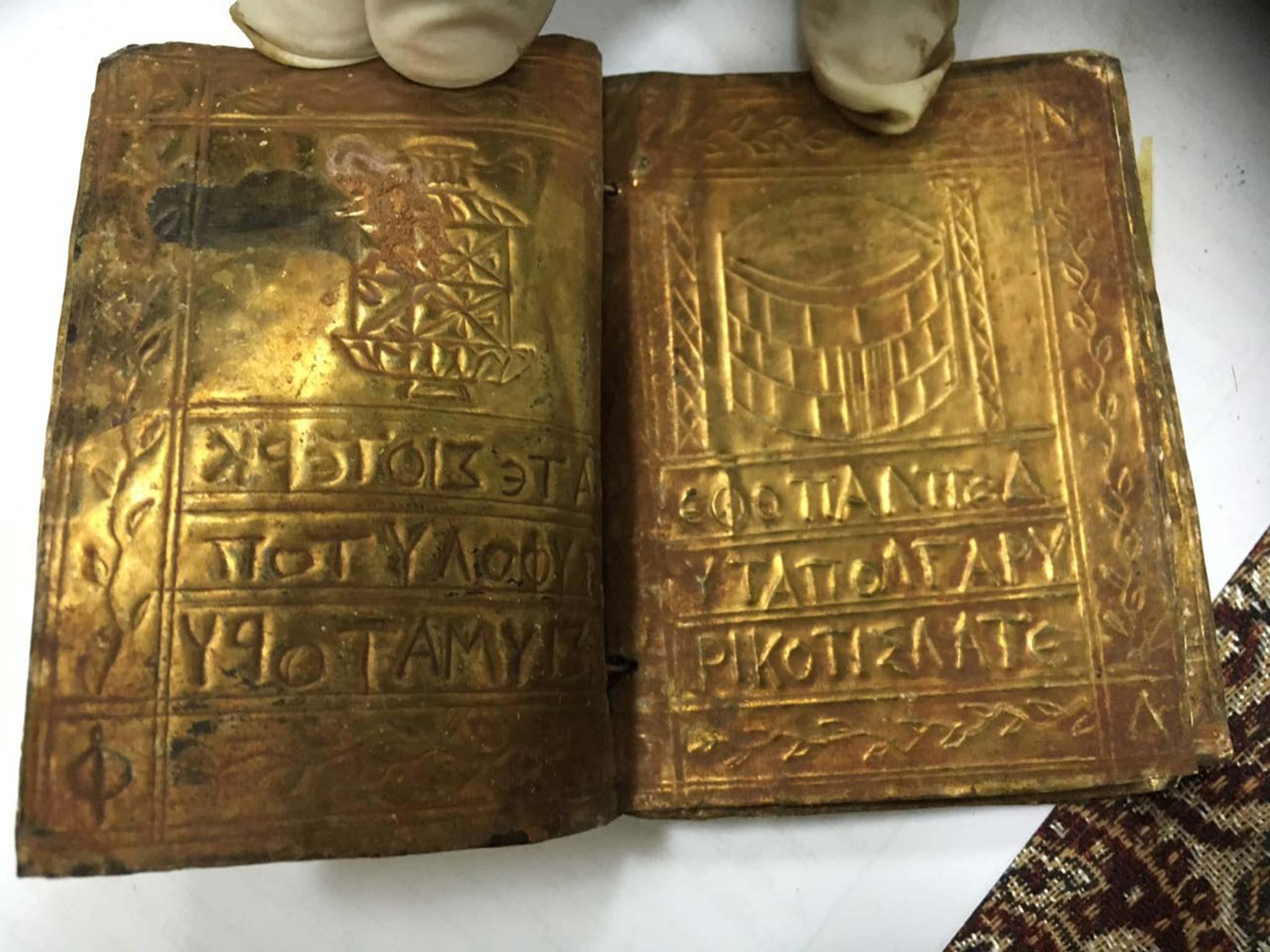

In the National Museum of Damascus are antique books of black magic or witchcraft listing curses and spells designed to dumbfound or destroy whatever enemy is targeted by the user. Alongside these tattered works lie a bible made out of copper, religious works from the Crusader period and, elsewhere in the museum, a striking stone statue of a falcon.

These look like impressive survivals from Syria’s past, but in reality all are fakes confiscated from smugglers on their way out of the country for sale to foreign customers and dealers. Expertly manufactured in workshops in Damascus and Aleppo or elsewhere in Syria, these fraudulent antiquities are flooding a market full of unwary or unscrupulous buyers who find it easy to believe that great masterpieces are being daily looted in Syria in the midst of the chaos and war. “It started happening in 2015,” says Dr Maamoun AbdulKarim, the general director of antiquities and museums in Damascus. “The looters had attacked all the ancient sites in 2013-14, but they did not find as much as they wanted, so they switched to making fakes.”

There is a strong tradition of craftsmanship in Syria and, in addition, though Dr AbdulKarim does not say so, many unemployed archaeologists and antiquarians are prepared to give expert advice to fakers. The results are often magnificently convincing and come from both government and rebel held areas. In rebel-controlled Idlib province the speciality is making Roman and Greek mosaics, which may be then reburied in ancient sites to reinforce belief in their authenticity and so the buyer can be shown persuasive film of them being excavated.

The smugglers are able to take advantage of the dangers of war which ensure that few potential purchasers will risk entering Syria in the middle of a conflict to check exactly what they are buying. They suppose that they can get a bargain because Isis and other iconoclastic Islamic movements are stripping ancient sites for ideological reasons and to raise funds – which is true, but not on the scale they imagine (It is not only fake artefacts from antiquity that are for sale, but modern documents bought by the foreign media that supposedly come from Isis but whose provenance and significance are dubious or exaggerated).

Some of the fake antiquities can be swiftly detected as such by specialists, but others are so expertly made that only laboratory analysis can prove that they are of modern manufacture. Sometimes the real and fake are mixed to make detection more difficult. In the National Museum, its director, Yacoub Abdullah, scoops out of a bowl Abbasid, Roman and Byzantine coins and rapidly sorts them into two piles, muttering “fake-real; fake-real” as he does so. Some items, such as the black magic or witchcraft books made from the skin of bulls, are seized by the police without the museum staff knowing where they came from.

Dr Abdulkarim says that 80 per cent of supposed antiquities being smuggled out of Syria into Lebanon are fakes, compared to about 30 per cent a couple of years ago according to the Lebanese authorities. He adds that the smugglers know that if they are caught by the Syrian police they will get reduced sentences because they can show that they were not –though for entirely self-interested reasons – robbing Syria’s heritage.

Smugglers benefit from Syria being the cradle of civilisation, containing many of the earliest agricultural settlements and cities in the world. Some sites are famous, such as the great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus with its wonderful 8th century mosaics showing scenes of daily life at the time of the Arab conquest, or Dura-Europos, the Hellenistic city called “the Pompeii of the Syrian desert”, famous for the frescoes in the early Jewish synagogue, fortunately removed long ago to Damascus. Unluckily, thousands of important sites are in the most war-torn parts of the country such Ebla in Idlib province, a Bronze Age city from the second and third millennium BC. Others, such as Mari from the third millennium BC, are on Isis-controlled territory and are vulnerable to systematic destruction, looting and neglect. Pictures show deep holes dug by looters every few yards.

Many wars throughout human history have led to the loss of ancient masterpieces of art and architecture or the archaeological remains of past civilisations. The causes of destruction have usually been threefold: damage due to fighting, looting for profit, and ideological objections to certain types of art such as the representation of divinities or religious themes. Europe has seen all these forms of depredation, notable examples being the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries and the area bombing of cities in the Second World War.

The five-year-long Syrian civil war has combined these three causes in a uniquely destructive manner: there is warfare reaching every part of the country; a prolonged break down of law and order opening the door to looting; and the rule over much of eastern Syria of a religious cult in the shape of Isis that targets ancient remains as polytheistic in a way that may have no parallel in history.

The impact of all this has been devastating: Aleppo and Homs have been shelled and bombed for years at a time. Dr AbdulKarim warns that “if Aleppo goes on being a battlefield it will become like Warsaw in 1944”. The al-Madina Souk, which had over 700 traditional shops, was burned out and the Grand Mosque damaged. Damascus, Aleppo and Homs – the three largest Syrian cities – are full of “ghost districts” where every building is shattered and walls still standing are pitted with holes made by bullets and shrapnel. In Palmyra, Isis infamously blew up the Temple of Bel and vandalised or destroyed other buildings and statues.

This tale of destruction and violence might lead on to think that the story of the attempt to preserve Syria’s heritage is one more depressing story of failure in the face of greed and fanaticism. So, to some extent, it is, but the stereotypical media picture of unstoppable triumph of evil in Syria is, on present evidence, not really true. The news is not all bad and, when it comes to Syria’s past, far more is being saved than has been lost. “We should not be pessimists,” says Dr Abdulkarim, who was appointed director general of antiquities and museums in 2013, a job for which he takes no pay and who regards himself as politically neutral. Of Armenian-Kurdish origin – his father was a survivor of the Armenian genocide in 1915 who was adopted by a Kurdish family – he revels in Syria’s ethnic and cultural diversity and wants to do what he can to preserve it. He and his 2,500 staff, some of them in rebel-held areas, keep in touch with local communities who are often protective of archaeological remains in areas where they live.

Devastating though the losses have been, no major museum in Syria has lost its contents through looting or destruction, though some have come frighteningly close to disaster. Trucks carrying items from the museum in Palmyra left for Damascus three hours before Isis captured the city in 2015. Some 24,000 objects were moved to safety from Aleppo and 30,000 flown out of Deir Ezzor on the Euphrates in the east of the country, including 24,000 cuneiform tablets. “I thought Isis were going to take the city at any moment,” says Dr Abdulkarim. “I could not sleep for nights.”

He adds that when he became an archaeologist he hoped he would spend his career “discovering treasures, but in the last three years I have spent all my time hiding them”. Once rescued artefacts reach Damascus, they are placed in secret vaults, along with the contents of the National Museum, which is long closed. In its empty rooms are today stacked with old army ammunition boxes filled with broken sculptures from Palmyra, some shattered by Isis beyond repair but others in fragments that have all survived and can be painstakingly pieced together again.

Destruction of the antiquities of Syria has not been anything like as total as was once feared. It has been resisted by Syrian archaeologists and communities alike. Khaled Assa’ad, the 82-year-old ex-director of Palmyra and Antiquities, was publicly beheaded by Isis in the city last August as a leading intellectual and because he would not tell them where treasures were to be found – though there may have been nothing to tell since they had been evacuated. The very fact that the great majority of antiquities being smuggled out of Syria today are fakes is backhanded evidence that the smugglers and their employers have failed to plunder as many original and irreplaceable artefacts as they wanted. The Syrian past, like the Syrian present, may be more durable than it looks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments