The politics of starvation: Syria’s civilians go hungry after months of sieges

From the enclave at Homs surrounded by President Assad’s forces to the Shia towns in rebel territory, deprivation pock-marks the map

“Bread is a dream for children inside Yarmouk Camp,” says Fuad, a Syrian Palestinian music teacher who tries to help bring food to the 20,000 Palestinians besieged inside Yarmouk. Standing by a barrier of sand and rubble that blocks an entrance to the camp in south Damascus, he adds that “people have been trapped in there for 185 days and are sick because they are eating weeds we used to feed our animals”.

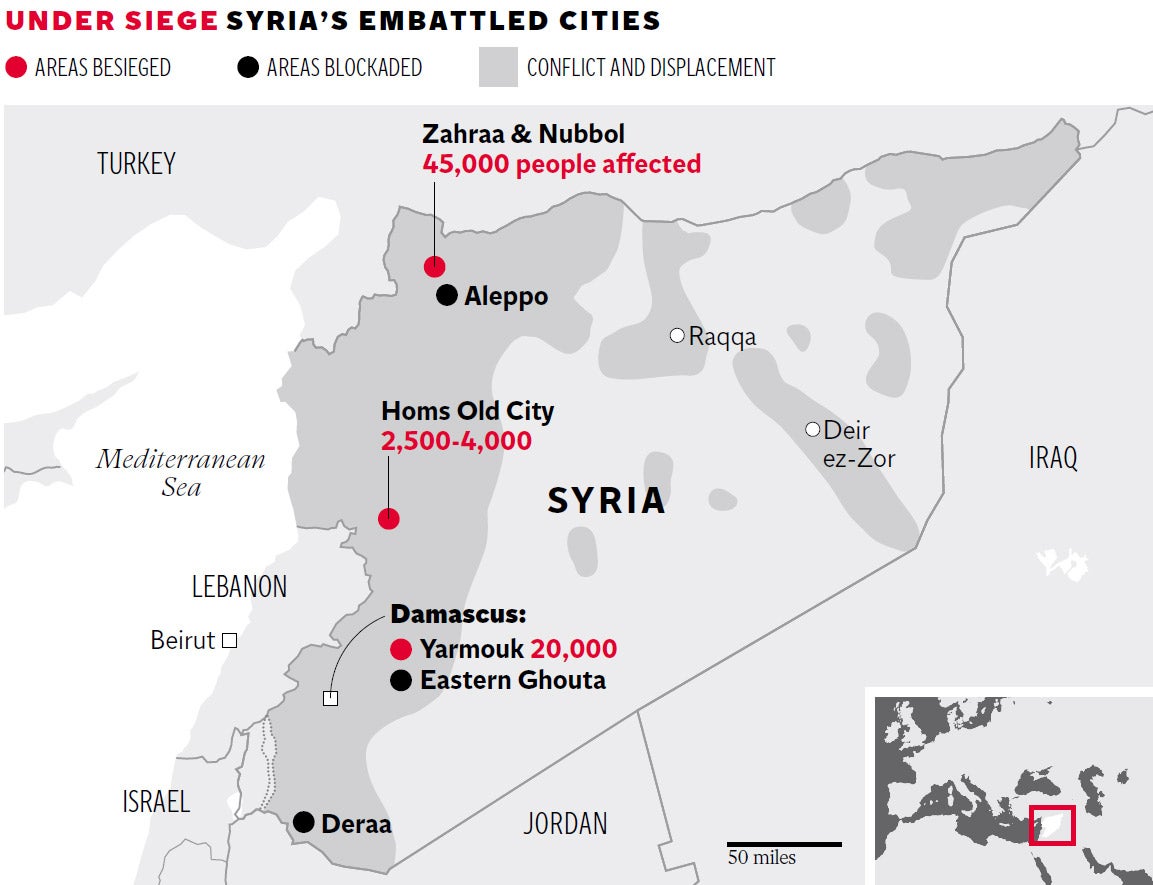

Syria is dotted with sieges and blockades of cities, towns and districts which in some cases are producing mass starvation. International attention is currently focused on the Old City of Homs where between 2,500 and 4,000 civilians are besieged along with several thousand rebel fighters.

A World Food Programme convoy waits for permission to enter from the Syrian government. It says it does not want the aid to go armed opposition fighters.

Unnoticed by the outside world, the largest single community currently besieged and on the edge of starvation in Syria lives in two Shia towns west if Aleppo, Zahraa and Nobl, with a combined population 45,000. In this case the besiegers are Sunni rebels who accuse the Shia townspeople of supporting the government of President Bashar al-Assad and are seeking to starve them into submission.

Zahraa and Nubl form an isolated Shia pocket in an area where most of the people are Sunni supporting the rebels. The towns have received no supplies from the outside apart from an occasional delivery by a government helicopter. Raul Rosende, the head of the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Syria said: “We are concerned about the situation in Zahraa and Nubl where 45,000 people are under siege.” A few Shia have escaped into Turkey and then crossed back into Kurdish-controlled north-east Syria.

The politics of starvation are complex in Syria and open to manipulation for propaganda purposes. The problem stems primarily from the government forces’ strategy of sealing off areas that have been captured by the armed opposition and not letting people or goods in or out.

Electricity and water is usually cut off, then the Syrian Army bombards the area with artillery and from the air, leading to a mass exodus of refugees. This approach has the advantage from the government point of view of avoiding house-to-house fighting in which their best troops would suffer heavy attrition.

Not all sieges are as tightly maintained as Homs Old City, Yarmouk, Zahraa and Nubl, but blockades still cause serious deprivation and intense suffering. People may not be dying in the streets but the very young, very old and very sick pass away earlier than would otherwise have happened. The biggest opposition-held area near Damascus is the Eastern Ghouta to the east of the capital, where 145,000 are estimated by the UN to be cut off from the outside world, but this rebel bastion is so large that it difficult to seal off entirely.

The Old City of Homs is a small part of a city, large parts of which were once held by rebel fighters, but these have gradually been squeezed out. Although the government has sought to seal off the Old City for a long time, its defenders were able to bring in supplies through a network of tunnels until last summer.

They also had a supply line running through the town of Qusayr to Lebanon, but this was lost after an assault by Syrian Army and the Lebanese paramilitary group Hezbollah in May and June of last year. An estimated 400,000 Sunni in Homs have taken refuge the al-Waar district in the west of the city where they are penned in but not completely confined by government checkpoints and barricades. But in the Old City, Mr Rosende says: “The situation is very bad and getting worse and worse, especially when it comes to food and medicines.”

In places like Homs where the two sides have been shooting at each other so long, UN agencies have to agree the exact minutiae of every movement by an aid convoy. Even where the Syrian Foreign Ministry has agreed that aid should be allowed through, local army commanders may be obdurate and uncooperative. Though Homs does not have many jihadis from al-Qa’ida-type organisations like Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State of Syria and the Levant (ISIS) as there are further north, the rebel leadership in the Old City is fragmented. As for the civilians, these are a mixture of fighters’ families, very poor people who have nowhere else to go and people who simply do not want to move.

Every siege and blockade in Syria involves suffering for the victims but otherwise every situation is distinct. The siege of Yarmouk, the Palestinian area in Damascus once called “Little Palestine” and home to 160,000 people, is only one element in the disaster that has hit the half-million Palestinians in Syria. Fuad, the music teacher who is trying to emigrate to Egypt, says “it is a second ‘al-Nakba’ for us”, the first al-Nakba or catastrophe being the Palestinian expulsion in 1948 from what became the state of Israel.

All the Palestinians in Syria are caught up in this new disaster because their camps after 1948 were usually built on the outskirts of cities such as Damascus and Aleppo. They were therefore right in the path of Syrian rebel forces advancing from the countryside in 2012 and five camps have some presence of the armed opposition.

Palestinians living in a swathe of camps in south Damascus fled first to Yarmouk and then fled again when the rebels took most of it over. Palestinians tend to be poorer than Syrians.

The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinians believes that “440,000 Palestinians need help and half of them are displaced within Syria.” Between 30,000 and 50,000 have become refugees in Lebanon. The network of schools and hospitals that was administered by the UNRelief and Works Agency A has collapsed.

There was not much fighting today around the northern end of Yamouk near the al-Majid mosque, though walls were pock-marked from past skirmishing.

The Syrian government, backed Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, has secured the far northern end of the Yarmouk, but beyond this a medley of opposition armed groups are in control. Here a kilo of rice cost $40 compared to $2 a kilo outside the besieged area. Dogs, cats and stray donkeys are being killed and eaten. There has been no electricity for nine months and only four hours of water every three days.

An UNRWA aid convoy was told by the government to use the southern rebel-controlled entrance to the camp – rather than the safer northern entrance – and found it was in the middle of a gun battle. In eight days, UNRWA was only able to distribute 138 parcels of food each weighing 30 kilo and miserably inadequate given the number of people to be fed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments