Campaign against Isis: Is there any hope for military success?

Britain's policy in Syria and Iraq depends on two partners on the ground: the Iraqi army and the moderate Syrian opposition to Assad and Isis. But the former is weak and the latter barely exists. Patrick Cockburn reports

British planes may soon be bombing Isis in Syria as well as Iraq, but so far the British Government has produced a picture of political conditions in both countries that hovers somewhere between wishful thinking and fantasy.

The Government agrees that air strikes must be conducted in close partnership with ground forces, if they are to have a decisive impact. But the partners it has in mind are the Iraqi regular army, which is still a wreck after its defeats in 2014 and earlier this year, and the “moderate” armed opposition in Syria, which is so feeble that it barely exists. When the US tried to create one it ended up with just four “moderate” fighters – individual fighters – in Syria at a cost of $500m.

Yet the Defence Secretary Michael Fallon was this week claiming that our allies on the ground are going to be “moderate opposition forces in Syria who have been fighting the regime in Syria and resisting Isil [Isis]”. He did not identify these elusive moderates, but the Syrian armed opposition is dominated by three extreme Islamic fundamentalist groups, of which the most powerful is Isis, followed by the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham, a hard-line Sunni movement. The one place where moderate and secular rebel groups had some strength was in southern Syria between Damascus and the Jordanian border. But they are in disarray since they launched an offensive in June called “Southern Storm”, which was beaten back by the Syrian army.

In Iraq, Fallon says that we are cooperating with the regular Iraqi army, which he claims is very different from the one that ran away last year. He says that at the time in June 2014, when 3,000 Isis fighters defeated at least 20,000 Iraqi army soldiers and captured Mosul, the Prime Minister of Iraq was Nouri al-Maliki, who ran a highly sectarian Shia-dominated regime. Fallon is encouraged by the fact that he has been replaced by a more inclusive government under Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. But inside Iraq this new government is seen as even weaker and more dysfunctional than its predecessor. Its main source of authority is its control of Iraq's diminished oil revenues, but otherwise it has little power outside Baghdad. Though heavily supported by US air strikes, its best military units fled Ramadi on 17 May. General Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, commented caustically that “Iraqi forces weren't 'driven out' of Ramadi, they drove out on their own”.

We have been here before: in 2003 in Iraq and again in 2006 in Afghanistan, Britain committed troops to conflicts which it made little effort to understand. The primary aim was to remain America's closest ally, regardless of the risks or the real situation on the ground. The outcome was humiliating failure for British forces based in and around Basra, Iraq's second largest city, who ended up being penned into their camp at the airport and ceding power to the Shia militias inside Basra.

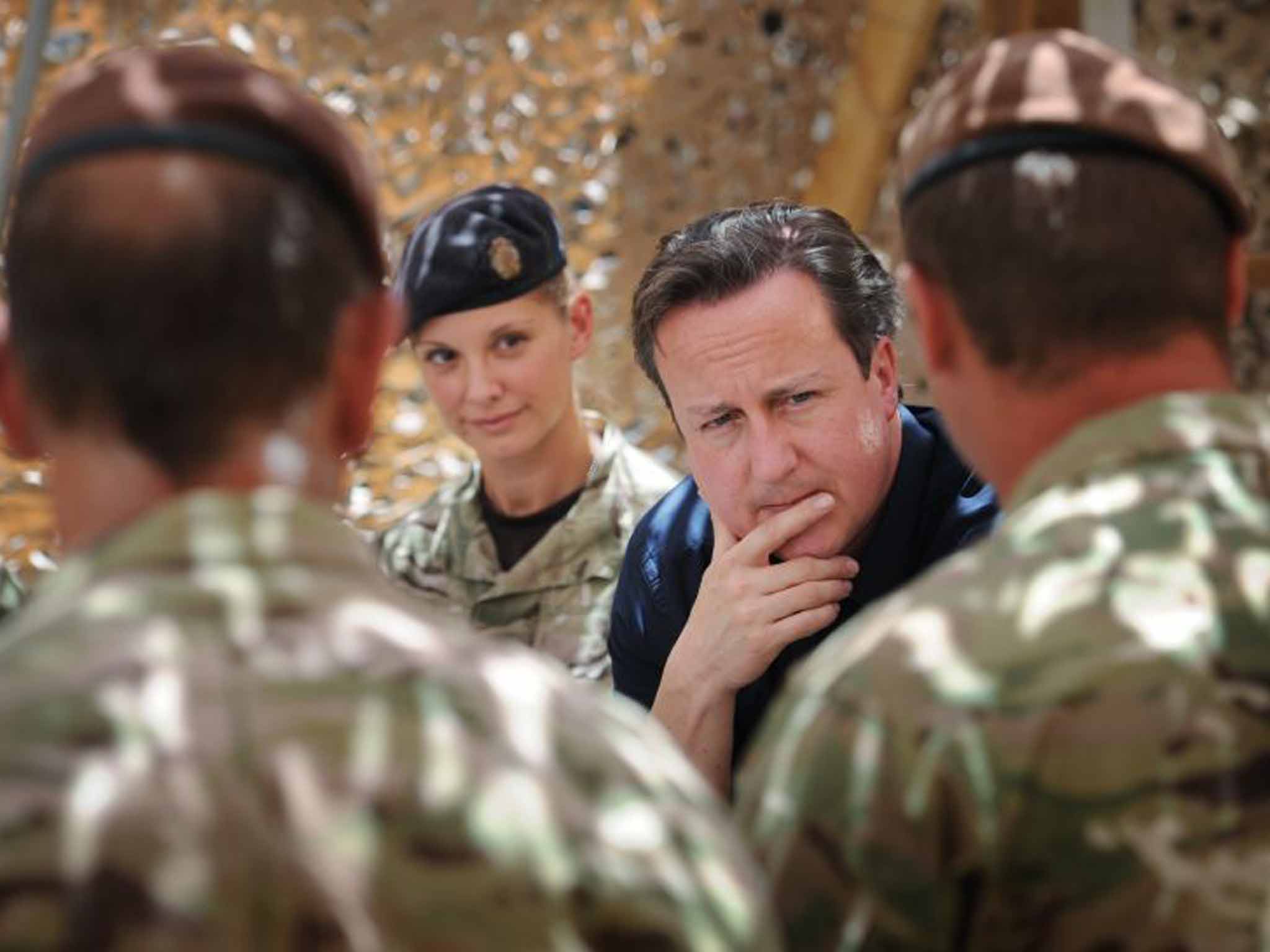

Redeployment of units to Helmand in Afghanistan in 2006, with complete disregard for the politics of the province, was even more disastrous and led to 456 British service personnel being killed for no particular purpose. In Libya in 2011, Britain joined a Nato air campaign, supposedly to save the people of Benghazi, which turned into a war to overthrow Muammar Gaddafi as Libyan leader. Trumpeted as a success by David Cameron at the time, four years later Libya has disintegrated, devastated by war and ruled by rival warlords who plunder the country. Libya's collapse has helped destabilise much of North Africa, leading to hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees cramming into unseaworthy boats in desperate attempts to reach Europe. In Syria, the downing of a Russian plane by Turkey yesterday shows the danger of unforeseen events.

There is a pattern here, which Britain may be about to repeat by extending its air strikes to Syria and stepping up its war against Isis. It will be the fourth campaign Britain has launched in the wider Middle East over the past 12 years and all have ended badly. The biggest failure has been political rather than military. Yet, in the days since Isis attacked Paris on 13 November, all the talk in Britain has been about more money for the Army and security personnel, and not for the Foreign Office.

But the most striking feature of Britain's response to the growth of Isis over the past three years has been that it did not know it was happening. When Isis captured Mosul, the political section of the British embassy in Baghdad was manned by just three short-term diplomats, according a report by the House of Commons Defence Committee. For in all four of these campaigns, the over-riding purpose has been to be seen as a great power and, above all else, fight whoever the Americans are fighting.

This carelessness about political consequences carries the seeds of military defeat and would have astonished British diplomats of an earlier generation. “Political and strategic preparations must go hand in hand,” wrote Sir Eyre Crowe, a famed Foreign Office Permanent Secretary more than a century ago. “Failure of such harmony must lead either to military disaster or political retreat.”

It could be argued that British air strikes in Iraq, and potentially in Syria, will be limited in scope and therefore the impact on Britain will be small. But it is always dangerous to dabble in war – and that is just what Britain did in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya – because the response of the other side is unpredictable and may be disproportionate.

In the case of attacking Isis, it is important to take on board that its leaders see the slaughter in Paris as a great success. At the cost of losing between eight and ten suicide bombers and gunmen and spending $100,000, its name has echoed around the world. It may be execrated, but it has shown its strength as it did when it destroyed the Russian aircraft over Sinai on 30 October. This makes it all the more likely that British people will be the target of retaliation, with tourists being the easiest victims as they were in Tunisia. This is not a reason for modifying future policy, but it is worth keeping in mind that Isis is committed to retaliating against its enemies with suicide squads instructed to kill as many civilians as possible.

There is a further point to keep in mind about the American-led air campaign against Isis: it has demonstrably failed in terms of its original intention, which was to contain and if possible eliminate Isis. There have been 8,289 air strikes by the US-led coalition in Iraq and Syria in what is officially called “Operation Inherent Resolve”, of which 6,471 have been conducted by the US. Regional allies such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, whose participation was much publicised when strikes on Syria started, have almost entirely disappeared from the scene and their planes are largely engaged in bombing Yemen. There have been 57,301 sorties in Iraq and Syria, indicating that most of the time pilots do not find a target and return without using their weapons.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt US commanders fervently believed at first that airpower alone could prevent Isis repeating its blitzkrieg victories of 2014. Unlike many wars, the exact moment this policy fell apart can be precisely dated: on 15 May this year, Brigadier General Thomas Weidley, chief of staff for Operation Inherent Resolve, gave a press briefing in which his message was upbeat.

He said: “We firmly believe Daesh [Isis] is on the defensive throughout Iraq and Syria, attempting to hold previous gains, while conducting small-scale, localised harassing attacks, occasionally complex or high-profile attacks, in order to feed their information and propaganda apparatus.” They were words he soon came to regret: even as Weidley was speaking, Isis fighters fought their way into the last government-held positions in Ramadi and the city fell two days later – on 17 May – to be followed by the Syrian city of Palmyra five days after that.

It is worth looking a little more closely into the reasons for the loss of Ramadi, because Isis is essentially an Iraqi organisation that expanded into Syria in 2011. It holds big cities in Iraq such as Mosul, Ramadi and Fallujah, while in Syria much of its vast territory there is desert or semi-desert, and the only city it holds of any size is Raqqa.

At the time of the loss of Ramadi, the Iraqi army was reckoned by informed observers to have only about 12,000 combat troops which could be used in battle, though it had thousands more who could man checkpoints or plunder the civilian population (the al-Abadi government had admitted to 50,000 “ghost solders” whose salaries were being paid to none-existent officers and defence ministry officials. According to Lieutenant General Mick Bednarek, the senior US military officer in Iraq from 2013 to July this year, speaking in an interview with Reuters, the army now has five depleted divisions whose fighting capacity is between 60 and 65 per cent.

In an interesting sidelight on the Iraqi army rout at Ramadi, he says that the flight of government forces started when an officer in the Iraqi Special Forces withdrew his men because he was anxious about missing out on an official trip abroad. The sudden and unexpected departure of his unit led to a panic among other Iraqi soldiers who fled en masse, enabling Isis to capture the city.

Supposing the Iraqi army now has 50,000 soldiers, though this is probably an exaggeration, it is smaller than the Shia paramilitary forces that claim 100,000. The three biggest militias are Badr Organisation, Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq and Ketaeb Hezbollah, all under Iranian influence, but well-trained and highly motivated. They are very popular among the Shia majority and find it easier to get recruits than the regular army, dogged by its reputation for corruption and failure. Moreover, there is no clean division between the army and the militias, since the latter largely control the Interior Ministry and at least one army division is said to report direct to militia commanders and not to the Defence Ministry.

In Iraq, Britain will therefore be acting in cooperation with an army that is no longer the strongest military force in Iraq. In Syria, by way of contrast, the British will be refusing to cooperate with the Syrian army, which is the largest military force in the country, and which is now backed by Russian air power. The Syrian opposition has always pretended that the Syrian army was not fighting Isis, though this is demonstrably untrue and the Syrian army suffered a string of defeats near Raqqa last year and again at Palmyra this May. But it was losing ground this year up to the moment when it was rescued by Russian air strikes and greater Iranian and Lebanese Hezbollah intervention on the ground. It has been taking back territory lost to Isis in the east and al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham in the north. And on 10 November, it broke Isis's siege of Kweiris military airbase, freeing some 2,000 Syrian troops trapped there in its greatest success for two years.

But it is by no means clear that greater Russian and Iranian military involvement will do more than restore the situation to what it was before the opposition's offensives earlier in the year. Russian intervention is, in fact, somewhat less effective than the Russians claim and their critics denounce. The Russians say that they had 50 aircraft – though many will be helicopters – active in Syria and these were reinforced by a further 37 aircraft last week, though some of these are bombers based in Russia. This is probably not enough to break the long-term stalemate on the battlefield or to capture the rebel-held half of Aleppo. Likewise, much is made of greater Iranian involvement, but General Joseph Dunford, the new chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, says that Iran has fewer than 2,000 troops in Syria and 1,000 in Iraq. As with the Russians, both the Iranians and their enemies exaggerate the extent of Iranian commitment to Syria.

There are other forces involved in Syria and Iraq. The Syrian Kurds have become the US air force's favourite ally over the past year and have maybe 25,000 well-organised fighters. They have taken half the frontier with Turkey, robbing Isis of entry and exit points. But the Kurds do not want to be used as cannon fodder by the US and Turkey is adamant that it will not allow them to advance west of the Euphrates. The Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga have also recaptured Sinjar in a well-publicised attack supported by heavy US air raids, but Isis had decided not to fight to the last man there.

Britain is becoming committed to a military campaign of exactly the kind that Eyre Crowe, the Foreign Office mandarin, warned against. Political and military preparations have not gone hand-in-hand, but have entirely failed to complement each other. In Iraq, Britain is seeking to cooperate with an army that is weak and defeated, while in Syria it will refuse to cooperate with the army which is the most powerful military force in the country. In the recent past such disharmony has produced failure and defeat. It could well do so again in Syria.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments