A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: The Turkish holocaust begins

3-24 April 1915: The overnight arrest in Constantinople of hundreds of intellectuals was the first public act of the war’s most terrible crime. Robert Fisk on the Armenian genocide

“About 50,000 Armenian refugees were flooding down the road… It was an amazing and tragic sight,” British Army medical officer Alan Glenn wrote years after he saw the survivors of the greatest war crime of the First World War. “There were old men and women and children… Now and then, we passed at the roadside a dying person, or one already dead and half-eaten by dogs… We could do nothing for them… Craig told me later that he attended an old refugee in the road who, before he died, gave him a leather belt full of sovereigns, which he asked him to spend to help the refugees.”

Greater love hath no man. Glenn’s memoirs of Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, his manuscript difficult to read on the fading, typewritten paper lying among his widow’s papers when she died in 1984, were published by his sons only last year. Thus we can now read another precious, independently witnessed, albeit tiny, fragment of the vilest act of the 1914-18 war – the annihilation in 1915 of 1.5 million Armenian Christians by the Ottoman Turks and their “special units” of mass murderers. Glenn was watching the Armenians die in north-west Persia more than three years after their genocide began, an event which prefigured the Jewish Holocaust and one which was almost formally instituted with the overnight arrest in Constantinople (now Istanbul) on 23 to 24 April 1915 of 235 Armenian academics, politicians, lawyers and journalists. Another 600 were later detained.

All were sent to Anatolia, most of them slaughtered. The Armenians, the government declared, were traitors; they were in league with the Allies, especially Tsarist Russia, against the Ottoman Empire. They were stabbing the empire in the back. The Nazis would use the same routine in their rise to power a few years later.

Then began the rape, pillage, torture and mass murder of the Christian men, women and children of Turkish Armenia. So awful were the killing fields that stretched from Turkey into the deserts of Syria that entire rivers changed their course because the mountains of Armenian corpses thrown into them blocked the waters of the Euphrates.

Unlike the Nazi genocide of the Jews, the West knew of the Armenian mass slaughter within days because Western missionaries and international diplomats – the United States was still neutral – witnessed the death marches and the piles of bodies at first hand. The Allies warned the Turks that this was a war crime of unparalleled proportions. They were right. The Bryce report, published by the British Foreign Office in 1916, faltered only when it came to describing in detail the mass rape of Armenian girls.

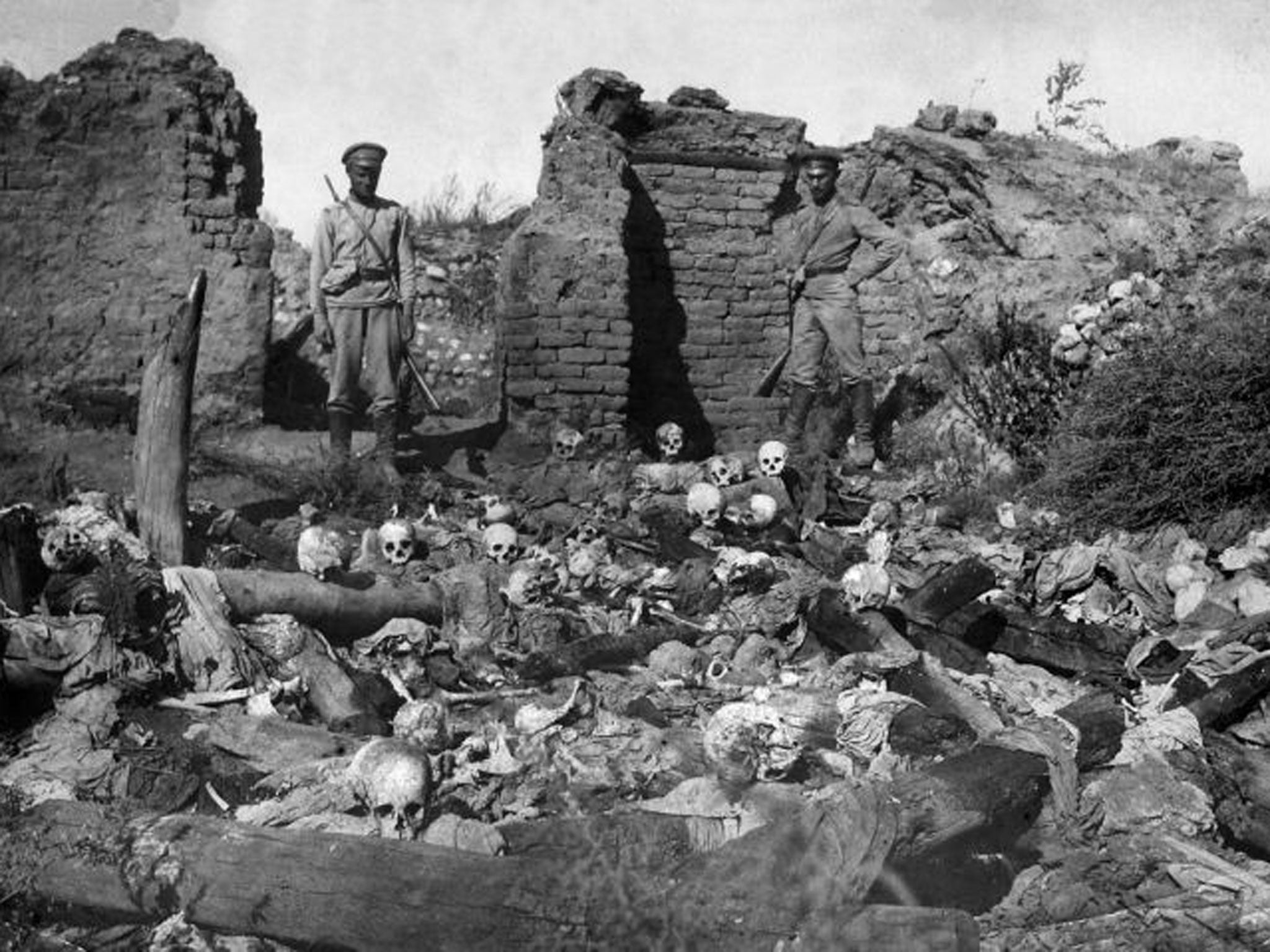

But save for a few hangings after the war, the Armenians were later abandoned. They never received the status of nation state which the 1919 Treaty of Versailles was to have awarded them. To this day, and to its immense shame, Turkey officially denies that its Ottoman ancestors committed an act of genocide. And also to its shame, the Israeli state denies that this terrible crime was a genocide – even though individual German officers training the Turkish army at the time and who witnessed the deportation and executions of Armenians (in one case posing next to the skeletons of the dead) later performed precisely the same acts of mass murder against the Jews of the occupied Soviet Union in the Second World War. Fearful of upsetting modern-day Turkey, Tony Blair colluded at a “genocide day” in London to which the Armenians were not originally invited. A confidential Foreign Office briefing in 2007 mendaciously concluded that “it has proved extremely difficult to disentangle the truth” about the Armenian genocide.

Against such grand lies the Armenians still gather up, jackdaw-like, every scrap of evidence of their people’s First World War persecution, every forgotten account – such as Glenn’s – and every fearfully snatched snapshot of the doomed, every recording of the few survivors, every buried document (especially foreign and thus more undeniable to Turkey’s holocaust deniers) in every archive. For Armenians, the denial of their Holocaust is as evil as it would be if Europe denied the Jewish Holocaust. The genocide of the Armenians remains the one blood-boltered event of the First World War which is still – to this day – denied by those who committed this monstrous crime. German atrocities against Belgian civilians or the Austro-Hungarian mass slaughter of Serbs pale beside the Armenian calvary.

So here are a few, largely unpublished memories of those who knew the Armenian genocide was real. Read them, and think of another genocide, just a quarter of a century later, in Nazi-occupied Poland and Nazi-occupied Belarus and Ukraine and Russia. Here, for example, is Sam Kadorian from Harpoot, only seven or eight when his family were sent on the death march:

“Some time later, Turkish gendarmes came over and grabbed all the boys from five to 10 years old… They grabbed me too. They threw us all into a pile on the sandy beach and started jabbing us with their swords and bayonets. I must’ve been in the centre because only one sword got me… nipped my cheek… here, my cheek. When it was getting dark, my grandmother found me… It hurt so much. I was crying and she put me on her shoulder and walked around. Then some of the other parents came looking for their children. They mostly found dead bodies. The river bank there was very sandy. Some of them dug graves with their bare hands – shallow graves – and tried to bury their children in them. Others just pushed them into the river, they pushed them into the Euphrates. Their little bodies floated away.”

And here is Astrid Aghajanian, who died in England only last year, talking to me in the final years of her life:

“At a village one night, my father, who had been deported with us, came to see us. He told my mother that he thought he was being allowed to say goodbye, that he would be shot with the other men. I remember my mother told me that my father’s last words were: ‘The only way to remember me is to look after Astrid.’ We never saw him again… It was a long march and the Turks and Kurds came to carry off girls for rape… My other grandmother died along the way. So did my newly born brother, Vartkes. We had to leave him by the roadside. One day, the Turks said they wanted to collect all the young children and look after them. Some women, who couldn’t feed their children, let them go. Then my mother saw them piling the children on top of each other and setting them on fire. My mother pushed me under another pile of corpses… My mother saved me from the fire. She used to tell me afterwards that when she heard the screams of the children and saw the flames, it was as if their souls were going up to Heaven.”

The Iranian writer Mohammad Jamalzadeh was travelling from Aleppo to Constantinople in 1915:

“Right at the beginning of our journey we witnessed unbelievably and unspeakably shocking and extraordinary scenes: we saw numerous groups of Armenians who were being escorted by armed mounted Turkish soldiers being driven to their death, towards annihilation… At first, it was very shocking to us. However, later it became so common that we would not look at them. Hundreds of Armenian women and men along with their children in a miserable condition were being driven along on foot, under the blows of whips and guns… whipping them along like flocks of sheep.”

An Austrian architect and engineer called Litzmayer – we do not know his first name, but he was working for the German government on the Baghdad railway – saw a large army moving towards him north of Ras al-Ain. He thought it was a Turkish army heading for Mesopotamia. In the words of Armenian priest Grigoris Balakian:

“As the crowd came closer, however, [Litzmayer] realised that it was not an army but a huge caravan of women, moving forward under the supervision of soldiers. They numbered… as many as forty thousand… They had known hopelessness and physical hardship, starvation, filth, abduction by Kurdish and Circassian mobs, pillage, and so on… They were mere skeletons enveloped in rags, with skin that had turned leathery, burnt from the sun, cold, and wind … When these wretched women met the Austrian engineer… they surrounded him and begged him to give them each a piece of bread. Litzmayer made every effort.”

When Sarah Aaronsohn arrived in Palestine by rail from Turkey in December 1915, she was in a state of shock. Her brother was to describe how “she saw the bodies of hundreds of Armenian men, women and children lying on both sides of the railway… Dogs were observed feeding on the bodies. There were hundreds of bleached skeletons.” Sarah’s train, according to the historian Scott Anderson, was besieged by thousands of starving Armenians. In the stampede, “dozens fell beneath the wheels of the train, much to the delight of its conductor”. Because she expressed her horror at the scene, Sarah, who came from Ottoman Palestine and was Jewish, was condemned by Turkish officers on the train for her “lack of patriotism”.

Winston Churchill was the first to call the Armenian genocide a “holocaust” – in fact, he called it an “administrative holocaust”, emphasising its organised and industrial nature – and many hundreds of thousands of Israelis, unlike their pusillanimous government, today acknowledge the Armenian genocide. “There is no reasonable doubt that this crime was planned and executed for political reasons,” Churchill wrote. “The opportunity presented itself for clearing Turkish soil of a Christian race opposed to all Turkish ambitions, cherishing national ambitions which could be satisfied only at the expense of Turkey.” The atrocities, Churchill was to write, “stirred the ire of simple and chivalrous men and women spread widely about the English-speaking world”. Not for long.

For when Turkey commemorates the 1915 battles at Gallipoli next year – joined by the British, Australians, New Zealanders and French – it will take the opportunity to smother further the memory of the gorgon crime which it carried out against the Armenians during the First World War, a people-killing that began at almost the hour of the first Anzac landings. Guests from Britain and Australia and New Zealand and France will not mention the fate of the Armenians which began the day their own soldiers stormed ashore at Gallipoli.

On the Somme, more than a million men were killed or wounded. They were all soldiers. But a million-and-a-half civilians were killed in Armenia’s Somme. And we – our representatives, our diplomats – will ignore them when we meet the Turkish genocide deniers at Gallipoli next year. And thus, so say the Armenians, we will help to kill the dead of their First World War Holocaust all over again.

Tomorrow: Bloodbath at Anzac Cove

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks