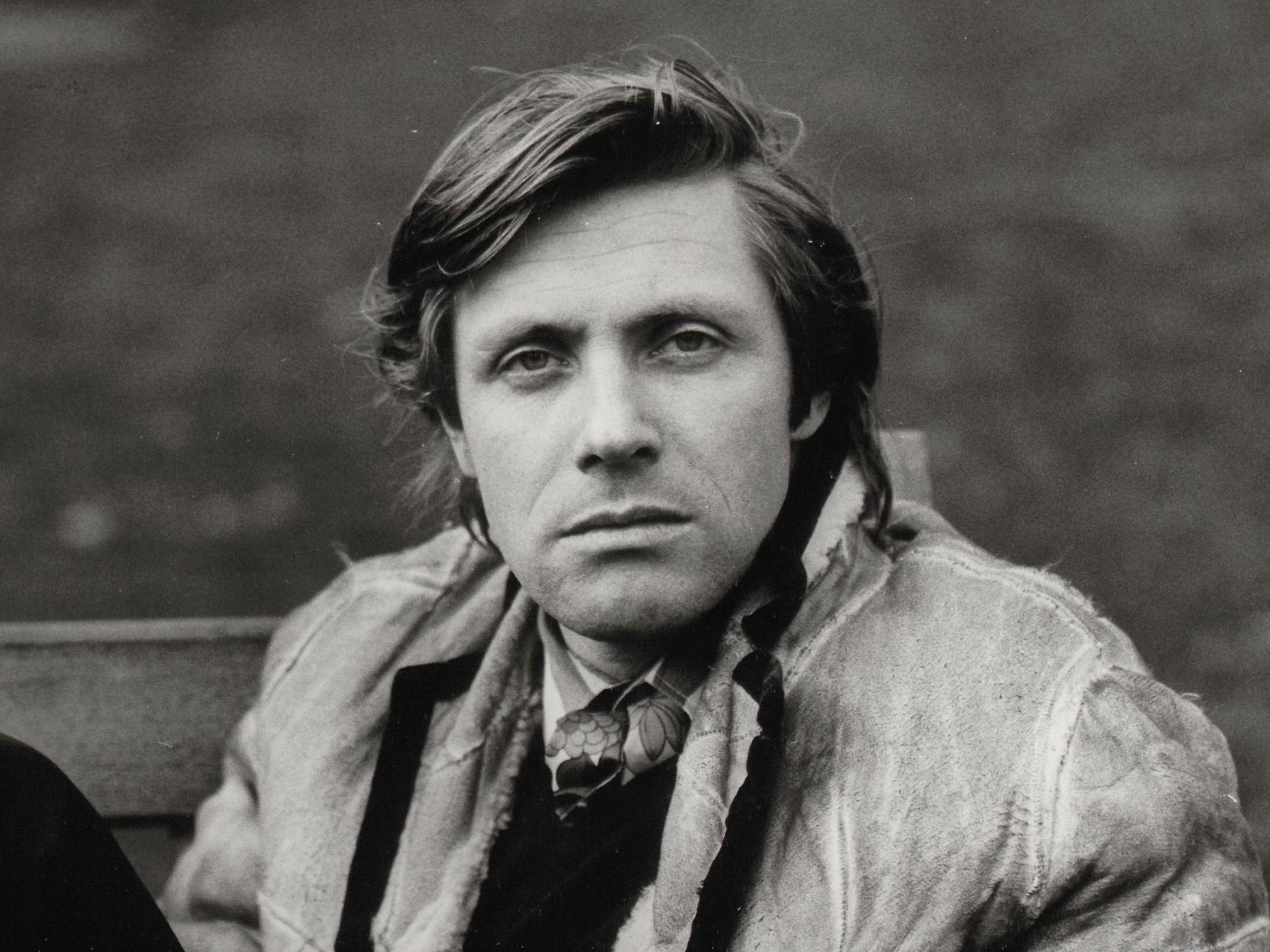

Peter Whitehead: Filmmaker who captured the countercultural drift of Swinging London

His work with the Rolling Stones made his name but he also covered poetry, protest and a society in flux

Peter Whitehead was a British film director who perhaps more than any other captured the raw, hedonistic rush that characterised Swinging London of the mid-1960s.

Although preferring classical music to pop, Whitehead, who has died aged 82, found himself at the epicentre of the city’s burgeoning rock scene and is best known for directing the first documentary on the Rolling Stones, 1966’s Charlie Is My Darling, 1967’s Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London and several pioneering pop promos for the likes of Nico, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, PP Arnold and the Small Faces.

Handsome and charming, Whitehead was a raffish Flashman of the counterculture, taking celebrated beauties as lovers and fathering eight children, on first-name terms with famous musicians, actors, poets and directors, before settling in the Middle East as a falconer. While Whitehead’s films never experienced any commercial success – and many of his projects were cursed with problems – he lived a charmed life.

Whitehead was the only child born to a working-class family in Liverpool and, after his father returned from serving in the Second World War, the family shifted to London where they lived in considerable poverty.

His father died from cancer as Whitehead won a scholarship to Ashville College, an elite Yorkshire public school. Here he transformed himself into “a gentleman” and demonstrated his many talents, from captaining the school rugby team to playing organ in the chapel. His academic performance gained him a scholarship to Peterhouse College, Cambridge to study physics and maths.

Disillusioned by science and increasingly fascinated by mysticism, Egyptology and the arts, Whitehead enrolled at the Slade School of Art in 1963 as a painting student but quickly gravitated towards the film department. He left Slade to work as a freelance filmmaker and established Lorrimer Books, dedicated mainly to publishing scripts by contemporary European directors, particularly Jean-Luc Godard.

He took his camera to the festival of Beat poetry at the Royal Festival Hall in summer 1965 and so shot his first short film, 1966’s Wholly Communion. Andrew Loog Oldham, the manager of the Rolling Stones, employed Whitehead to make a documentary of the Stones’ 1965 Irish tour – Charlie Is my Darling (1966) – and a number of promotional films for his Immediate record label, one reason that Whitehead is now considered a founding father of the pop video.

The Rolling Stones through the years

Show all 30Charlie Is My Darling is a remarkable slice of cinema verite, capturing the Stones at their raucous, charming, pop star peak, yet due to a dispute between Oldham and Alan Klein (the American who Oldham went into partnership with to manage the Stones) the film was never officially released and considered lost until 2012 when it was issued on DVD and finally screened on the BBC. Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967) was a more ambitious, if cynical, documentary about London’s rock and movie stars and beautiful people.

That same year his documentary Benefit Of The Doubt, focused on the Peter Brook staging of the anti-Vietnam war play US with the Royal Shakespeare Company. In 1968 he shifted to New York to film The Fall, an ambitious documentary of student protests and a society in flux, but during the filming he suffered a nervous breakdown.

In 1970 he was back in London and filming Led Zeppelin in concert at the Royal Albert Hall. He co-directed with French sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle the rarely seen 1973 feature Daddy. He directed 1976’s Fire In The Water, starring his then partner Nathalie Delon (with cameos from John Lennon and David Hockney), a film few have seen.

Having struggled with the limits of film making since The Fall, Whitehead cited an existential crisis that lead to him leaving the UK and dedicated the next 15 years to falconry, eventually building the world’s largest falconry for the Saudi royal family.

In 1980 Whitehead married Dido Goldsmith, the niece of Sir James Goldsmith, fathering four daughters – the eldest, Robyn, died of a drug overdose in 2010 (the rock musician Peter Doherty would subsequently be jailed for his role in supplying Robyn with cocaine).

The Gulf War put an end to Whitehead’s sojourn in Saudi Arabia and, returning to the UK in 1991, he focused on writing and self-publishing mystical novels. He suffered a serious heart attack in 1996 and this forms a centrepiece for The Falconer, Iain Sinclair and Chris Petit’s controversial, fictionalised documentary on Whitehead.

Paul Cronin’s two-part documentary In The Beginning Was the Image: Conversations with Peter Whitehead, mixed new and archive interviews and helped revive interest in Whitehead’s films. Based on his 2007 novel of the same name, 2009’s Terrorism Considered as One of the Fine Arts, was Whitehead’s last film. He and Goldsmith divorced in 2002 and a subsequent marriage to Liza Kareninam ended in divorce. He is survived by six daughters and one son.

Peter Whitehead, filmmaker, born 8 January 1937, died 10 June 2019

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies