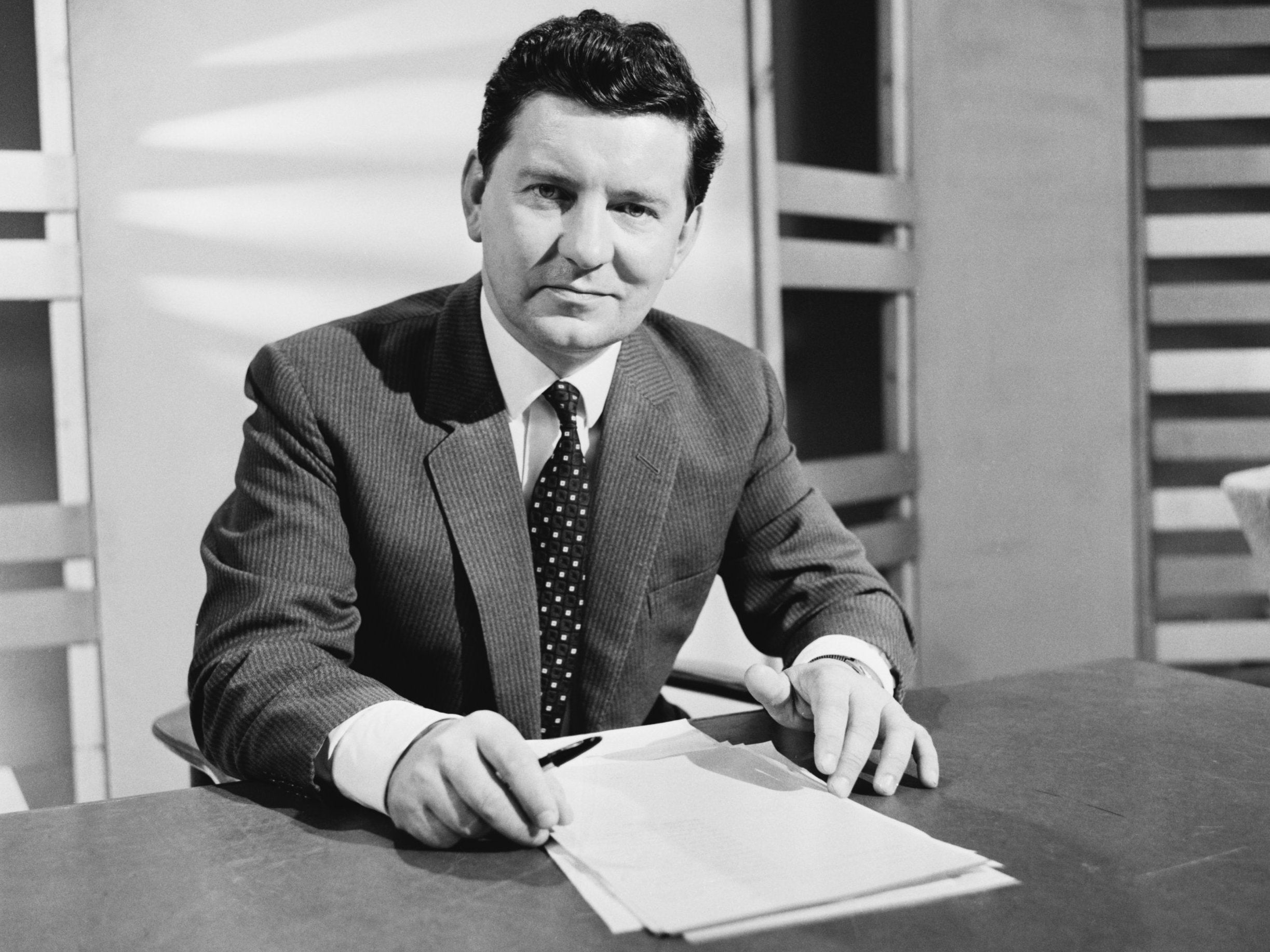

Richard Baker: newsreader who introduced first BBC television bulletin

His mellifluous, well-modulated voice and friendly face made him a comforting presence in the nation’s living rooms

The qualities required of a television newsreader are not easy to define. Richard Baker described his own approach in his 1966 memoir, Here is the News:

“I try to imagine two or three people sitting around the fire at home. What will get across to them will be the quiet communication of facts, the appearance of easy confidence... confidence without cockiness, restraint without frigidity, friendliness without being too cosy. Somewhere there that elusive balance lies.

“We belong to that strange race of television men who are paid simply to talk to other people. It ought not to be difficult. But the more you do it the more you realise it is. We are television non-personalities. It is a paradoxical craft.”

Yet to classify Richard Baker, who has died at the age of 93, simply as a newscaster is to undervalue his varied talents and his contribution to the nation’s cultural life. While he first made his mark as one of the two original faces of BBC News – a role he took up in 1954 and maintained for 28 years – his interests and abilities ranged wider, embracing naval history, the stage and classical music, of which he was a deeply knowledgeable devotee.

He wrote nine books and was a familiar voice on radio, where he presented numerous programmes about music and was for 17 years the host of Start the Week on Radio 4. A man of pride and spirit, he would respond sharply to any who sought to dismiss him as a dullard who simply read other people’s words off an autocue.

In 1976, by then a household name, he was lampooned by Atticus, the waspish columnist of The Sunday Times, in a regular feature entitled “Impersonalities”, devoted to poking fun at the famous in doggerel:

“His leaden wits defuddled by the clique

Of prating hacks, alleged to Start the Week:

An emptiness where bores and half-truths breed,

Supposing he can think, as well as read.”

The following week Baker responded with a rather wittier verse of his own:

“This rhymester, sir, upon your final page,

This callow castigator of the age –

When wanton crimes on every side grow worse,

Must he be paid to vandalise in verse?”

And after chastising his critic for inaccuracies, he concluded:

“Enough of this, my leaden wits collapse –

But even they can comprehend perhaps

This nameless fool’s pathetic fit of pique –

He’s never yet been asked to Start the Week.”

This is not to say that Start the Week was altogether free of Atticus’s “prating hacks” and “bores”, many promoting their latest books. Baker was aware, though, of the danger of allowing the them too easy a ride: “There is an endless supply of people with something to say but there is a risk of overdoing the plugs,” he once said. “So that’s the reason one adopted a slightly abrasive style.”

Richard Douglas James Baker was born in 1925 in Willesden, north London, the son of a plasterer from Lincolnshire. In his 1989 book Richard Baker’s London he revealed that as a child his interest in music and the theatre was encouraged by his parents and relatives. They took him to music halls, films and concerts, including one of the early Promenade Concerts in Queen’s Hall (destroyed in wartime bombing). Later the Proms were to play an important role in his career.

From Kilburn Grammar School he won an exhibition to study history at Peterhouse, Cambridge; but in 1943, on reaching 18, he joined the Royal Navy, with a view to completing his degree later. After training at Tobermory on the Isle of Mull, he served as assistant gunnery control officer and entertainments officer on HMS Peacock, a frigate performing escort duties on the western approaches. This meant accompanying convoys to and from the mid-Atlantic and Arctic, with the constant danger of attack by German U-boats.

The Navy made a lasting impression on him. In the 1970s he would write biographies of two senior officers who crossed his path. The Terror of Tobermory was about vice-admiral Sir Gilbert Stephenson, who had been in charge of his basic training, and Dry Ginger told the story of admiral of the fleet Sir Michael Le Fanu, who died of leukemia in 1970.

In 1946 Baker went up to Cambridge, where he indulged his enthusiasm for amateur dramatics to the extent that, after graduating, he joined a series of repertory companies and briefly featured in cabaret. “There is nothing I enjoy more than appearing in a stage entertainment,” he confessed in Richard Baker’s London; but he could not earn a living at it, and in 1949 he took a job teaching English at Wilson’s Grammar School in Camberwell.

“It seemed to me that teaching was among the most splendid of vocations,” he wrote in Here is the News. “It is also an extremely difficult job, as I was to discover.”

Still searching for his true vocation, he applied to the BBC and in 1950 was engaged as a trainee studio manager. After two years he was made an announcer on the Third Programme (now Radio 3), but only after taking compulsory elocution lessons.

“I went to a voice teacher and laboured to change my As and Os, which I was told sounded a bit cockney,” he recalled in 1977. The treatment clearly worked. His mellifluous, well-modulated voice, together with his friendly, slightly chubby face, would make him a comforting presence in the nation’s living rooms after 1954, when he moved into television news.

Although the TV service had been operating since before the war, the BBC had been chary about letting it compete with radio as an outlet for broadcast news. After an agonised debate it was decided to introduce an evening bulletin, but without at first exposing the newscasters to the cameras. This is how Baker described it:

“All I did in that first programme, at 7.30pm on 5 July 1954, was to announce, behind a filmed view of Nelson’s Column: ‘Here is an illustrated summary of the news. It will be followed by the latest film of happenings at home and abroad.’ We were not to be seen reading the news because it was feared we might sully the pure stream of truth with inappropriate facial expressions. Management relented in 1955 and allowed its television newsreaders to appear on screen. Kenneth Kendall and I were tried out on the late-night summaries, when it was hoped not too many people would be watching.”

As television found its feet and began to attract a mass audience, news coverage expanded, developing into an integral part of the daily schedule. Baker and his colleagues became familiar on-screen faces. As well as fronting the national news, they took it in turns to host the London regional current affairs programme Town and Around, while Baker presented a special Sunday evening bulletin for the deaf and hard of hearing.

This led to the first of his many awards, being chosen in 1964 by a charity for the deaf as television’s clearest speaker. In the 1970s he was thrice named Newscaster of the Year by the Radio Industries Club. Other forms of recognition were less flattering: he enjoyed recounting how, on a street in Glasgow, an inebriated man spotted him and cried out: “It’s wee fatty from the BBC!”

His 17-year stint on Start the Week began in 1970 and further enhanced his public profile. In his time the programme was a mixture of discussions with celebrity guests and some stunts more suited to television, as when he took on-air lessons in belly-dancing and when Esther Rantzen painted his feet red as part of an April Fool hoax. The revelation that this solemn purveyor of the world’s tribulations had a lighter side led to his guest appearances on programmes such as Monty Python’s Flying Circus and Morecambe and Wise.

In 1981 the BBC decided to rethink its approach to TV news bulletins. Hitherto many newscasters had been drawn, like Baker, from the ranks of aspiring actors. The new idea was to give the role to high-profile reporters, who would become more involved by conducting some interviews themselves. John Humphrys and John Simpson took over the main nine o’clock bulletin, while Baker was confined to the less prestigious six o’clock slot. After a few months he decided to give it up altogether.

His parallel career as a music presenter was, however, still thriving. From 1960 until 1995 he hosted the television coverage of the first and last nights of the Proms. He was also a regular on BBC2’s Face the Music, the polite, sotto voce musical quiz chaired by Joseph Cooper, with Joyce Grenfell and Bernard Levin among his fellow panellists. Over the years he presented many programmes of popular classics on Radio 2, 3 and 4. In his 1975 book The Magic of Music he wrote: “The snobbery that once divided ‘popular’ from ‘classical’ music is happily dying ... Music, in one form or another, is for every man.”

He was awarded the OBE in 1976 and in 1984 was named BBC Radio Personality of the Year by the Variety Club of Great Britain. In 1996 he was presented with the Sony Gold Award for a lifetime’s achievement in radio. The previous year he had switched to Classic FM but returned to the BBC, his natural home, in 1997 to present Melodies For You, Friday Night is Music Night and Your 100 Best Tunes – all on Radio 2 – continuing until he was over 80. Welcoming him back after his brief defection, the critic of The Sunday Times wrote: “Richard Baker’s face may have aged but his voice has not.”

Over the years he held a number of positions on prestigious musical bodies, including the Friends of Covent Garden and the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company. In 1961 he married Margaret Martin and they had two sons – to be seen as toddlers in several charming photographs in Here is the News.

In 2015, Baker and other veterans of the Arctic convoys received the Ushakov medal, awarded in recognition of the bravery of British sailors who assisted the Russian navy.

In his later years, Baker moved into a retirement home. Although he found it hard at first, he soon found an ingenious way of settling in. Each day he would select interesting headlines from the day’s newspapers and read them aloud to his fellow residents at six o’clock over dinner.

Baker’s son James said his father died on the morning of Saturday 17 November at the John Radcliffe hospital in Oxford.

Richard Douglas James Baker, newsreader and presenter, 15 June 1925, died 17 November 2018

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies