Amy Jenkins: There's a fine line between the rebellious and the farcical

Living on the edge

I spent much of my youth in seedy nightclubs. I'm a child of the sexual revolution. It's not really that easy to shock me. Yet the other day I saw a photograph that was so outrageously unsettling I found it very hard to get it out of my mind.

I was in my kitchen making a shepherd's pie, or something equally wholesome, when a friend showed me a photo on his phone that he'd been sent by Sebastian Horsley. The picture was of Horsley in Amsterdam. He was grinning at the camera, naked – with a prominent erection, and a prostitute splayed out underneath him. Run-of-the-mill stuff for Horsley. What made it worth the photo was the fact that the prostitute was a quadruple amputee.

Horsley's trip – apparently a Christmas present from his on/off girlfriend and ex-Page 3 girl Rachel Garley – had turned into a bender. Now, just as a play of his life opens, Horsley has been found dead, it seems from a heroin overdose. Did he really think – as he hinted – that now he'd seen his "doppelgänger" on stage it was time to "get his coat"? Was this the timely exit of a flamboyant character who'd attempted to live life as one long performance? Or was it the usual – a squalid junkie death following a misjudged overdose?

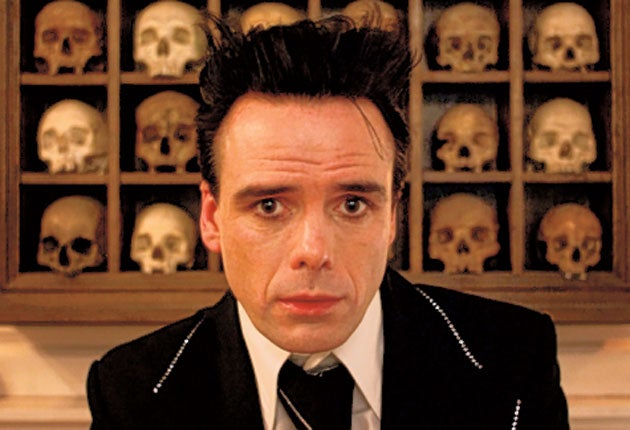

Sebastian Horsley liked to think of himself as Byronic; "mad, bad and dangerous to know", although his origins were a little more prosaic. The son of the Northern Foods chairman, Nicholas Horsley, Sebastian dedicated his life to repudiating the convenient and over-lit world of the supermarket. He longed for squalor and seaminess. He sought out pain, and famously had himself crucified. He was most gratified when America denied him entry for "moral turpitude". He saw himself as an artist but, not having any particular talent beyond the gift of the gab, Horsley made a work of his life.

The trouble was, the element of farce about it all ended up undercutting the Byronesque feel. When being crucified, his footrest slipped and he fell off the cross, which would have been funny if it hadn't been so gruesome. (His hands were ripped.) A friend says that the thing about Horsley was that he tried too hard. There was an air of desperation about him. He said his life was his art, but he didn't himself believe it. He was a self-loather who really thought himself a fake. In that sense, this wasn't farce but tragedy.

Which brings us to the prosaic truth behind Horsley's tireless performance. He made no secret of the fact that he was the child of alcoholic parents. "Clearly everyone in my life who should have been vertical was horizontal," he quipped. His mother was a self-confessed drinker, saying: "I don't think his father, Nicholas, ever went to bed sober and I was always in a fog." It's no wonder Horsley grew up an addict and, although he was in and out of remission thanks to 12-step programmes, he never really shook off heroin. It's almost impossible to fulfil your potential as a full-blown addict and however much Horsley liked to think of his life as an act of defiance, and a work of art, it was always mired in the realities of this painful (and terminal) disease.

To those who knew him, it was his addiction and the associated narcissism that comes with a damaging childhood which drove his need for attention and ultimately made his life seem more fundamentally sad than fundamentally inspiring. All of which is a shame, really. We need people to live differently and to challenge the normal way of things. We need rebels and renegades. Here's Horsley on his financial arrangements: "I invested 90 per cent of my money in prostitutes, the rest in class A drugs, the remainder I squandered." We like the fantasy that rules can be successfully flouted and that death can be metaphorically defied.

"Despite everything, he was essentially a kind, funny man," says his artist friend, Simon Tyszko. "I'd like to honour him with a minute's silence. The trouble is, that wouldn't be enough for Sebastian; he'd want an hour." He suggests fellow addicts could just "keep him in mind for the next 60 minutes".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks