Christina Patterson: What one very expensive faulty wire can teach us about right and wrong

It must have been quite a day.

It must have been one of those days when you go home and pour yourself a big glass of wine, even though you know, because you've just seen a programme about middle-class drinking, that you shouldn't. It must have been a really big glass of wine, because quite a lot of us pour ourselves quite big glasses of wine, even when all we've done is get through the day. But it must have been a really, really big glass of wine that Antonio Ereditato poured himself when he came home and told his girlfriend, or boyfriend, or mother, or whoever it is he lives with, if he lives with anyone, that he'd proved Einstein wrong.

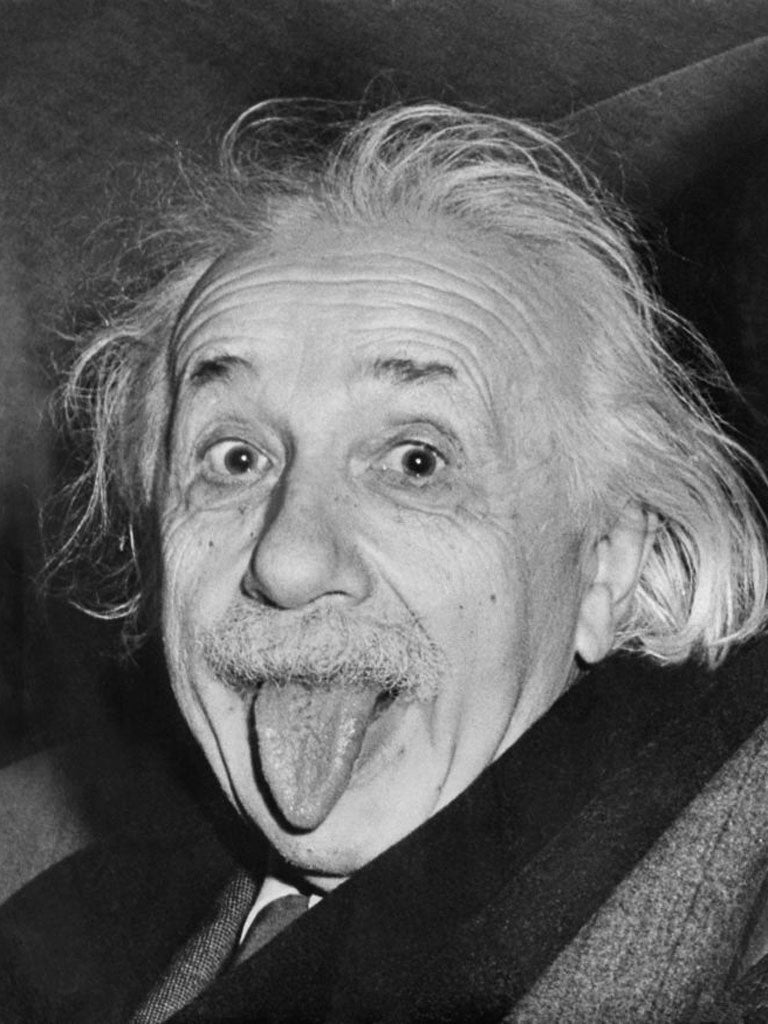

It must have been quite exciting to explain to her, or him, that he and his colleagues had been working on a project called "Opera", which wasn't the kind of project where people on a stage sang that their tiny hand was frozen, but the kind of project where tiny particles travelled through rock. And that those particles, which were called "neutrinos", which was a name that was easier to remember than the "Oscillation Project with Emulsion-Racking Apparatus", had travelled faster than the speed of light. Which meant that what you had just done, to get your glass of wine, was change the laws of physics.

But it can't have been quite such fun to go home, and tell your girlfriend, or boyfriend, or mother, as Antonio Ereditato must have done this week, that now it didn't look as though you had. That it looked as though what you'd done was run a very, very, very expensive experiment, and cocked it up.

It must have been quite embarrassing to remember that you had told the world that you had "checked and rechecked" for anything that could have "distorted the measurements", and that you'd done that for more than three years, and that you had "high confidence" in your results. And then to have to tell them that you thought there might be a problem with the "oscillator", which isn't the same as a carburettor, and with an "optical fibre connection", which other people might call a faulty wire. It must have been quite difficult to say that you were "looking forward" to "performing a new measurement of the neutrino velocity" when what you meant was that you never wanted to hear the word "neutrino" ever again.

You must have wanted to say, to all those people who were laughing about the faulty wire, that science was a lot more difficult than it looked. That you couldn't just have an idea and tell everyone you knew it was true. You had to follow a set of rules called the "scientific method". You had to follow them because people tended to see what they wanted to see, even in scientific experiments, and so you had to think of ways of testing your idea that you could repeat, in exactly the same conditions, and that other scientists could repeat, too. You couldn't change the tests to get different results, even though you might really want to. You just had, even when it was embarrassing, to stick to the results you'd got.

You must have wanted to tell the people who were laughing that almost everything they could see, unless they were sitting in the middle of a field, was there because scientists had looked at things, and tested them, and tested them again, and then again. You might have wanted to remind them that the lights they had on, and the heating they had on, and the phones they were using, and the computers they were using, were all there because scientists had done experiments which had sometimes gone wrong. And that you would never find out anything new, if you didn't sometimes get things wrong.

You might have wanted to tell the people who were laughing, who thought they were right about so many things, that there was a very, very big difference between having an idea, or view, and thinking it was a good idea, or view, and proving it was good in a way that no one could dispute. You might, for example, want to say to the people who said that the way to deal with an economy in debt was to cut a lot of spending that it might be, but we didn't know, and to the people who said that the way to deal with it was to borrow more, to spend more, that their guess was as good as yours.

You might want to say to these people that even if their approach looked as if it was working, since you couldn't "control" for other factors, you couldn't be sure. And that this applied to almost everything that politicians said, and to almost everything that anyone else said, and that what they were saying they were so sure about was just a view that hadn't been tested, and a view wasn't the kind of thing that anybody could say was "right" or "wrong".

While you were drinking the glass of wine you poured yourself, because you were feeling so embarrassed, you might think that it was strange that people who could never know if they were right seemed to think that they had used scientific methods to prove that other people were wrong. You might want to remind them that the important thing in science, and also in life, was that you had to keep looking, and you had to keep thinking, and that sometimes what you had to do, which was nothing to be ashamed of, was change your mind.

It's official - I'm now middle-aged

It starts with the A-Z. The little black marks in the index, that used to be names of streets you could look up, suddenly look like the tiny script you see on ancient tablets. You find yourself crouching by the headlamps of your car, and thinking that you now can't read small print in poor light, and then thinking that all light now seems to be poor. In the end, you crack, and get your eyes tested, and get told, but not in quite those words, that you're officially middle-aged. You try on lots of glasses, which all make you look like a marketing executive planning a murder, and which all cost, though you can't quite believe it, hundreds of pounds. And then you nip to Boots and decide that what you really want to look like, for just a few quid, is a very fierce librarian.

Twitter warnings from its boss

I had never, until yesterday, heard of Christopher Stone, but I think I like him. He's the co-founder of Twitter, and he has just told its 500 million users to turn it off, and do something else. "I like," he said, "the kind of engagement where you go to the website and you leave because you found what you are looking for, or you found something very interesting." And not, he didn't add, but might have, the kind of engagement where you tell your "followers" every single thing you do, all bloody day. I like Twitter, in tiny doses, but I'm with its boss. It's a tool. Get a life.

c.patterson@independent.co.uk // twitter.com/queenchristina_

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies