John Lichfield: Holidaying en masse: What France can teach us about the Big Society

The French love to do their own thing so long as everyone else is doing roughly the same. They love to break rules, but they expectthe state to clean up the mess

Most countries like to have 12 months in the year. Not the French. The official French year lasts for 11 months. It begins in September and ends in July. August is not just, as in Britain, a time for holidays. It is a time of mass exodus from reality; a hiatus; a pause in the immutable rhythms of normal life; a time to leave home and go and sponge on Grand-mère in her house in the country.

We are therefore approaching the annual Niagara Falls of the French year: the time when normality falls off a cliff.

For President Nicolas Sarkozy, the end of the month cannot come too soon. He hopes that, by the end of August, when France reopens for business, the country will have had its hard disk wiped clean by chilled rosé wine, suntan cream, cheap novels, byzantine family quarrels and dense traffic jams. The French will return to their ordinary lives with only a vague memory of the "Affaire Bettencourt" and its wonderfully convoluted suggestions of hypocrisy and greed and envelopes stuffed with cash in high places.

In France, September is not just called septembre. It is also called la rentrée, or the great return: the true start of the year.

There is a rentrée politique, when politicians and bureaucrats, like the inhabitants of Sleeping Beauty's castle, awaken in the hostile poses in which they fell asleep in July. There is a rentrée sociale, in which the trades unions revive all the grievances that they had agreed not to pursue in the late spring and early summer.

One of the reasons why the May 1968 student-worker revolt failed, according to French sociological lore, is that it happened at the wrong time. The protests petered out as students and workers drifted away on holiday. The proper time to mount a revolt in modern France is la rentrée, when you have at least three clear months of marching and striking before Christmas. (The revolt programmed, by common consent, for the rentrée this year is a protest against Mr Sarkozy's plan to raise the normal retirement age from 60 to 62.)

There is also the rentrée littéraire, when more than 600 new French novels – over half of all the novels published in the year – are tipped on to the bookshop shelves in a couple of weeks in early September. Most disappear without trace. Others are the subject of heavy promotion, and manipulation, by the big publishing houses as they compete, and connive, for the three or four big literary prizes awarded in the late autumn.

Worst of all, there is the rentrée scolaire (the return to school), a period of mental torture for children and more so for their parents.

Adults with small children return from holiday to a sadistic examination, set by teachers. The exam paper takes the form of an extensive and abstruse list of fournitures scolaires (school equipment), which Hortense or Guillaume or Mohammed must possess on the first day of school or face teacherly rage.

The parents must supply exercise books (of precisely stated dimensions and characteristics) plastic exercise-book covers (in specified colours), ink, paper, sticky tape, rolls of wire, paper plates, shoeboxes, scissors, paintbrushes, paint, painting paper, tracing paper, paper hankies and glue. Lots of glue. French teachers are addicted to glue.

The rentrée is, above all, a time to "get serious". My wife once committed the social faux pas of appearing on the streets of Paris on a sweltering day in September in sandals. The Parisians, and especially the Parisiennes, looked at her in horror, as if she were wearing a bathing suit on the Champs-Elysées. This was, after all, la rentrée. Sandals were "so August".

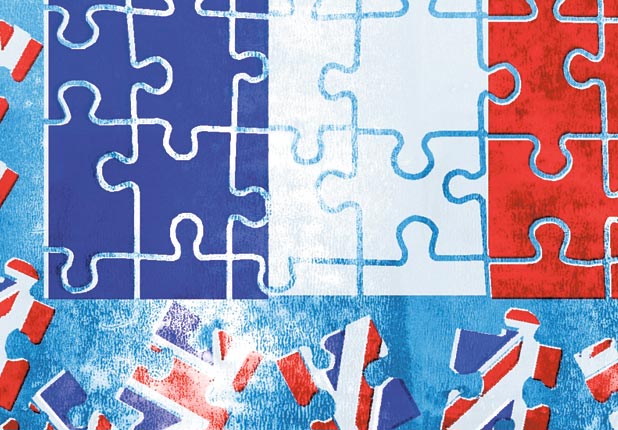

France is a country of self-absorbed conformists: a country of individualism en masse. The French love to do their own thing so long as everyone else is doing roughly the same. Punk styles have never worked in France. A few young French people try blue spiky hair and razor blades but they always look fundamentally French: too clean and instinctively well dressed.

This is, I believe, connected to another French conundrum: the ambivalent, almost teenaged French attitude to the state. French individualism is different from British individualism and very different from American individualism.

The French are as jealous in their own way of their individual rights, and fundamental privacy, as any nation. They love to break rules, when they can get away with it, even more perhaps than other nations. (Ask Thierry Henry.) But they also expect the state to be there to clean up the mess.

Teenagers want to be left alone; they want to be permanently in revolt from the household authorities; they also expect their washing to be done for them. Many, not all, French people – both on the political left and the right – live in a state of constant contempt for the state but constant expectation that the state should decide and provide.

In so far as I can understand it, David Cameron's Big Society programme is based on the notion that we should all do more for ourselves because a) it is good for us and b) the state can no longer afford to do so much. This may, or may not, make sense in Britain. There is already a flourishing voluntary sector in the UK. There are already fully private schools and hospitals and railways.

A "Big Society" approach in France would be truly revolutionary. Even so-called private schools and private medicine are partly funded by, and therefore partly controlled by, the French state. Almost all the sporting and community activities which would be run by well-meaning busybodies in the UK – from local football teams to village fêtes – are run, or largely funded, by some manifestation of la République in France.

My adopted village in Normandy will hold its annual fête tomorrow, a festival of sausage-grilling and pony jumping and a chance for everyone to clear the rubbish from their attics and replace it with the rubbish from other people's attics. In Britain, such an event would be privately or church run. In France, it is the clear, political responsibility of the village mayor and his seven councillors, the local, elected representatives of the state.

President Sarkozy was elected three years ago promising to, among other things, mess with the collective mind of the French: to make them more enterprising, more can-do, less tradition bound, less dependent on the state, less troubled by invisible barriers to advancement. He has, predictably, proved to be as ambivalent as the rest of France, an odd mixture of libéralisme, monarchisme and étatisme, with, it would appear, a typically flexible French attitude to rules.

After almost 14 years in France, I find myself equally torn between exasperation and admiration for the French way of doing things. Is Sarkozy's reluctance to cut into the bone of the French state cowardice or common sense? Do French savoir-vivre and qualité de vie exist despite, or because of, the many ritualised French hypocrisies?

Bof. Je m'en fous. Time enough to think about that in the rentrée.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments