Julian Baggini: Which of us can say we wouldn't avoid tax, given half a chance?

More important than the fairness of any particular law is the fairness which says we all need to obey it

Do you want to pay less tax? It's totally legal. Faced with such an offer, I doubt many of us would turn round and say, "No, thank you."

Jimmy Carr didn't when his financial adviser put exactly this suggestion to him. Even when tax evasion is illegal but easy, I'd like to know how many readers can honestly say that they have bypassed the opportunity for any reason other than fear of being caught. Given the choice between paying a builder £1,000 cash or a properly invoiced £1,200 plus VAT, I think most would opt for the lower figure.

Yet, according to David Cameron, Carr was "morally wrong", and public opinion agrees. So it seems that the vast majority would both pay less tax if they could and condemn Carr for doing exactly that. Call me misanthropic but I strongly suspect that the difference between Carr and most of the rest of us is not principle or integrity but lack of opportunity.

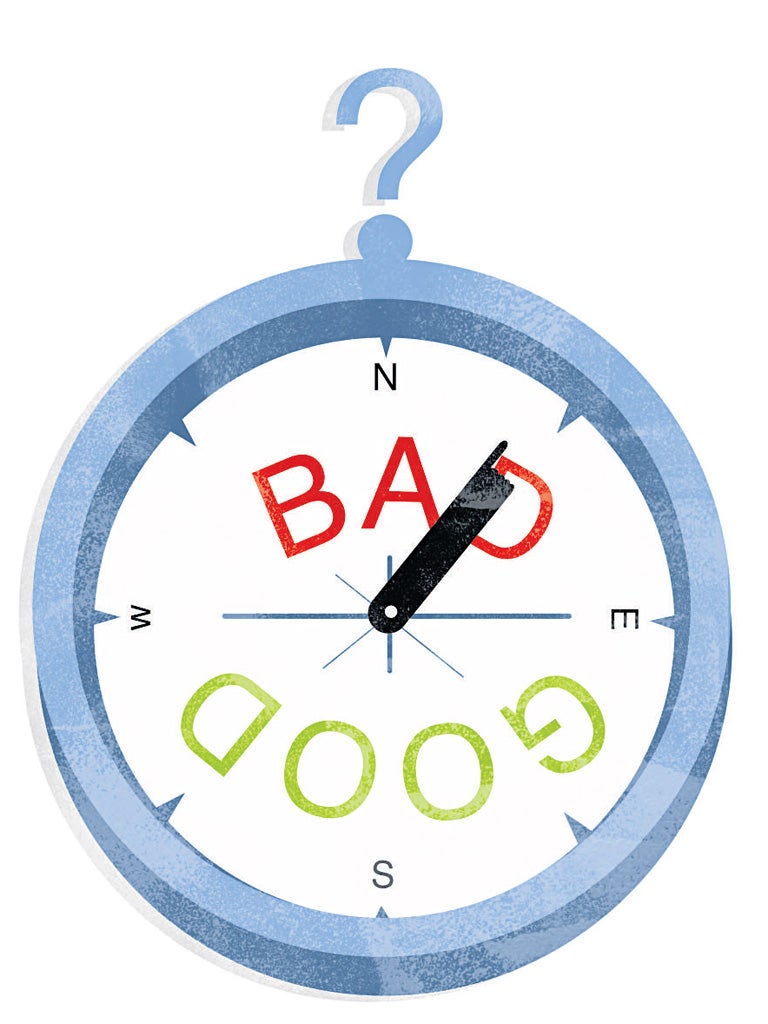

The point of thinking about this is not that there is a moral equivalence between reducing the tax bill on a massive income to around 1 per cent and being paid – or paying – a bit of cash in hand. The scale of avoidance routinely practised by the majority of millionaires is much more serious than occasional small-scale cheating. The value of the mirror that Carr's case holds up is not that it exposes our hypocrisy, but that it reflects a much deeper malaise: the way in which we exploit the difference between what is morally right and what is legal to suit our own ends.

The most obvious example of this is exemplified in the mantra which became ubiquitous during the MPs' expenses scandal in 2009: "I broke no rules." We heard it again from Baroness Warsi, whose expenses are currently under investigation but which she insists were "in accordance with the law". We've heard it from some of those identified by last week's reports by this paper into the undisclosed interests of Lords, with Lord Boateng saying, "I am not currently required by the House rules to list my professional clients", insisting that "any work for them is completely separate from my work in the House" and that he is "careful to avoid any actual or perceived conflict of interest".

To be fair to Warsi, she added that she also adhered to "the spirit of the rules", tacitly acknowledging that following the letter of the law is not good enough. This is important, because rules are not the same as principles, and from an ethical point of view, principles matter more. Rules are needed to fashion fundamental principles of justice and fairness into clear guidelines for action. But if the rules end up having the opposite effect, or permitting unjust action, we recognise that they are wrong and change them. So anyone who is concerned with no more than abiding by the rules is at the very least unconcerned with examining principles, and at worst keen to find ways around them.

At the same time as we often act as though rules and principles were the same thing as an excuse for being unprincipled, we are also perfectly capable of recognising the distinction between legality and morality to justify breaking the rules when it suits. It has been one of our better British traditions that we despise jobsworths who insist that "rules are rules" even when common sense suggests some flexibility is in order. But this admirable lack of rigidity can easily descend into moral contortion. If no one is harmed, if I have generally been more law-abiding than many others, if I deserve a bit of a break, then what is wrong with breaking the law on this one little occasion? To go back to the VAT-free builder's bill, the very fact the offer is on the table proves that plenty of other people are playing the avoidance game. So who wants to be the one mug who pays more? It's always possible to find a reason why it would not be wrong for us to break the rules just this once.

But it is vital to uphold the law, even when it is not just. More important than the fairness of any particular law is the fairness which says we all need to obey it. As Aristotle argued, respect for the rule of law is even more critical for a just society than democracy. After all, in a democracy, the majority can tyrannise the minority, but where there is a true rule of law, no one is above the law and everyone has the same rights. Bad laws should be changed, not flouted. There is, of course, always a place for civil disobedience, but only when other avenues for change have proved ineffective, and to work it always needs a public to act, not sneakily getting around the rules for our own benefit.

The much-valued British pragmatism does have its place, but there is a difference between applying rules with sensitivity to others and interpreting them liberally to suit ourselves. The former is a kind of compassion to others, the latter mere self-serving convenience. And even leniency to others needs to be handled with care. Much as we might value a police force that is prepared to let some unimportant transgressions go with a simple "just don't do it again", we unfortunately know that such flexibility has historically been selectively applied. Good old common sense turns out often to mean letting people with the right accents, clothes or skin pigmentation off and cracking down on these with the wrong ones.

So it is true that legality is not morality, and sticking to the law is necessary for good citizenship, but it is not sufficient. Unfortunately, be it MPs' expenses, abuse of privilege by the Lords or tax avoidance by the rich, we are all too adept at using the mismatch between law and morality to justify our own self-serving actions. We are not helped by a culture that is increasingly litigious, and which encourages us to sue or claim compensation if we have a technical case, whether or not the person or body we're trying to extract money from has actually behaved immorally.

The culture of litigation is simply the most evident sign of a disturbing shift in society from ethics to legality. We cannot know whether we would succumb to the same temptations that so outrage us in MPs, Lords and rich celebrities when we look on from outside their clubs. What we can know is whether in the situations we do face, we follow both the letter and spirit of the law, or whether we are willing to abandon either if it suits us.

Julian Baggini's latest book (with Antonia Macaro) is 'The Shrink and the Sage'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks