Rupert Cornwell: Never have hopes been higher – and never has the job been tougher

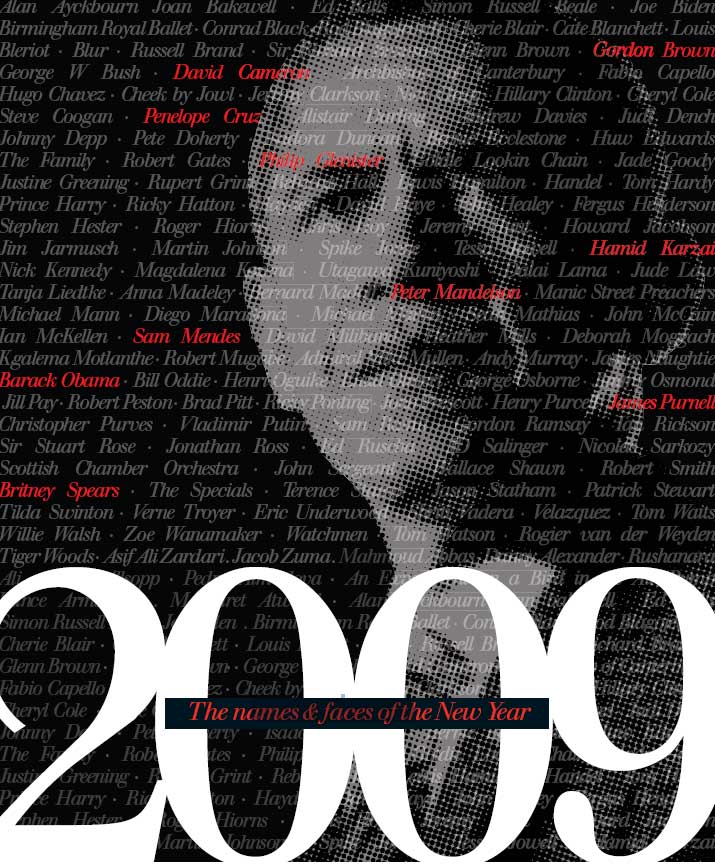

On 20 January, Barack Obama will become President of the United States. His preparation has been faultless. Soon, we will learn if all the optimism is justified

Barack Obama had it right. Postpone the first candidates' debate, John McCain was urging last September at the height of the presidential campaign, as the White House convened an urgent summit on its bank bailout plan, a day or two before the two White House rivals were to lock horns at the University of Mississippi.

The financial collapse, McCain argued, rendered everything else superfluous. But the Democrat was unmoved: "It's going to be part of the president's job to deal with more than one thing at a time." Those words of Obama are contender for 2008's understatement of the year. Never has an incoming President been confronted by as daunting an array of problems as the untried former Senator from Illinois.

Others have been put to stern test. Abraham Lincoln faced looming civil war when he took office in March 1861. In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt had to drag the country out of the Great Depression, an economic crisis worse even than the one Obama must deal with now. But for the 44th President, 2009 will be the year of multi-tasking. The unfinished business of two wars, and a dislocating economic downturn, are only the first items on his agenda. Around the globe, especially in the Middle East and South Asia, other crises simmer.

Hardly less pressing is the need to tackle the ever more glaring inadequacies of the United States's health and education systems, and at last to set about reducing the country's ruinous and unsustainable addiction to imported oil. But even these vast domestic challenges pale beside the global challenges – among them global warming, and the gulf between the world's rich and poor, that the economic downturn will only widen. In each case, action is essential, and soon.

Multi-tasking, in short, is putting it mildly. A better metaphor for the incoming Obama is the chess grandmaster as he plays a dozen games at once. And there's one other complication: all the matches are inter-connected. A wrong move on one board might spell disaster on another. Making the stakes even higher is the weight of expectation on our grandmaster's shoulders. Everyone expects him to win every match, and pretty much without breaking sweat. A Washington Post poll before Christmas found almost 70 per cent of Americans to be "optimistic" about Obama's policies over the next 12 months.

Whatever else, Obama's warm-up game has been well nigh faultless. Most transitions are either messy or slow. His has been extraordinarily focused and productive, and – barring the scandal over his home state governor, Rod Blagojevich – thus far without embarrassment. There is no true preparation for being President of the United States. But Obama has come as close as anyone could reasonably demand. A week before Christmas, when Bill Clinton was still waffling, Obama had already completed his cabinet. His might still be a shadow administration, but for a month now it has been quietly formulating policy – aided, it must be said, by a remarkable degree of co-operation from the outgoing Bush team.

Obama's voting record in the Senate might have been unequivocally liberal, but his appointments bespeak a pragmatic, non-ideological approach to America's and the world's problems. He has had the self-confidence to appoint his fiercest competitor for the nomination, Hillary Clinton, as Secretary of State, and to retain a successful Republican, Robert Gates, as his Secretary of Defence. His economic team comprises some of the mightiest intellects and reputations in the land. If Obama fails, it will not be through lack of talent at his disposal.

So what precisely awaits in the undoubtedly grim year that lies ahead? The most important change may be the easiest to achieve. The mere fact that Obama is not George W Bush has already burnished America's image in the world. His opposition from the outset to the Iraq war, the moderation of his pronouncements, his willingness to talk with Iran and other foes of the US, his multi-ethnic and multicultural background – all provide him a fund of goodwill none of his predecessors has enjoyed. Rightly or wrongly, people expect this first black President, the first born to a non-American father, to understand how the rest of the world sees America, and to act accordingly.

Some early steps are already clear. Within days of his inauguration on 20 January, Obama is expected to sign a mammoth economic stimulus bill, worth a total $800bn (£540bn) or more, in tax cuts and new government spending, much of it on infrastructure projects that create jobs and put money in consumers' pockets.

Shortly thereafter, he may announce a firm plan for the closure of Guantanamo Bay (though Obama, with his grasp of issues, realises that with Guantanamo, the devil is in the detail). It is likely he will make an early visit to a Muslim country – why not to Indonesia, where he lived as a child? – to symbolise his determination to rebuild America's broken relations with the Islamic world. By the same token, the term "war on terror" will probably vanish from his administration's vocabulary. Possibly, he may begin to dismantle the futile, half century-old US embargo against Cuba.

Speed is of the essence. Almost every president enjoys a honeymoon, and, barring uncharacteristic blunders, Obama will enjoy a longer one than most. He also has unassailable Democratic majorities in both House and Senate to turn his proposals into law. But the importance of a president's "first 100 days" cannot be overestimated. In those three months or so his influence is at its utmost. Patterns are set, and impetus is generated. It would be astonishing if Obama did not try to make progress on all fronts in this crucial early phase. That is, if he's allowed to.

Joe Biden, the Vice-President elect, was held to have committed a gaffe during the campaign when he noted that Obama would be "tested" by a foreign crisis within a few months of coming into office – maybe even in those talismanic first 100 days. In fact, the loquacious Biden was merely stating the obvious. The only question is where the crisis will erupt.

One possibility is a major terrorist attack against the US, or a tempting US target abroad. More likely is some new flare-up along the "arc of crisis" that stretches from North Africa through the Middle East and Iran and down into the Indian subcontinent. Scenarios abound; from breakdown in Pakistan to turmoil engulfing a key US ally like Saudi Arabia or Egypt, to renewed bloody confrontation between Israel and the Palestinians. None looms larger, of course, than a showdown with Iran, arising from either the irretrievable breakdown of diplomatic negotiations over Tehran's suspected nuclear arms programme or, worst of all, an Israeli strike on Iranian nuclear installations that plunges the region into chaos.

Two factors magnify the perils. The first is the deepening economic slump, which could easily dislocate already fragile balances, both within countries and between them. Rising unemployment and poverty are not only a threat to internal social stability. As history shows, only too often they lead to war. Reflexively, the world will look to America to resolve a crisis. In 2009, however, the US may have neither the resources nor – given its own economic mess – the will to get involved.

That mess may not (or at least not yet) match that of the 1930s. But the recession is the worst since the Second World War, and no one expects a glimmer of recovery until the second half of 2009. By then unemployment could have risen to 8 or 8.5 per cent of the workforce, compared to 6 per cent now. The budget deficit, some forecasters say, will hit $1 trillion, or 8 per cent of GDP. Thus the second danger, that the world expects more of Obama than he can deliver.

In 2009, the US may be less able to exert its power – at the very moment that power has never been more essential. As Zbigniew Brzezinski, once national security adviser to President Jimmy Carter, put it in a lecture at Chatham House in London, "no state or combination of states can replace the lynchpin role America plays in the international system". Similarly, the world economy will not recover until the US economy recovers. Thus "the only alternative to a constructive American role is global chaos".

The global interest in the 2008 election, and the outpouring of hope stirred by Obama's victory, merely underline Brzezinski's point. Alas, the hope may be excessive. Like any politician anywhere, Obama will put his own country's interest first – however much the 200,000 who turned out to see him last July in Berlin, and hundreds of millions more around the world, might wish otherwise.

Hope, neverthless, is preferable to despair. As that Washington Post poll showed, America is a country of inveterate optimists. Barack Obama's qualities as a statesman remain to be seen, but Barack Obama the symbol has already turned much of the rest of the world into optimists too. The question is, will we be feeling the same way at the start of 2010?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments