The case for a Bill of Rights

Criticised by many Tories, defended by the Liberal Democrats, the Human Rights Act is highly divisive within the coalition. In fact, it doesn't go far enough: if we care about liberty, we must create our own declaration, argues Geoffrey Robertson QC

This country has, in its history, law and literature, done more than any other to advance the liberty of the citizen against the State. Why, then, are we afraid of enshrining British freedoms in a written constitution or teaching them in any meaningful way to our children? The best New Labour could do was to adopt the European Convention on Human Rights, a Euro-prosaic expression of the freedoms that seemed in 1950 worth asserting against the threat of communism. Incredibly, it is this motherhood (really, grandmotherhood) document that has become the first bone of coalition contention: last month Nick Clegg was forced to defend it in hyperbolic terms against Tories who want to tear it up. It is a sad and silly dispute for parties which promised the electorate "real change" so as better to secure civil liberty.

This promise can only be achieved by moving on from the Euro Convention – building on it, but not abandoning it. The redneck conservatives who now want it ditched appear ignorant of the fact that it was their own legacy, supported at the time by Churchill's determination that the Council of Europe should provide some ideological bulwark against the blandishments of Stalinism. Indeed, after the Attlee government baulked at including rights to property, education and even democracy (because it hoped to nationalise banks and private schools, and was denying democracy to British colonies) these very rights were incorporated in the Convention by its first Protocol, ratified by Churchill in 1952.

Today, rights guaranteed by the Convention are not so much fundamental as elemental. The document was modelled on the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, designed by Eleanor Roosevelt's UN committee, after the Nuremberg trials, as a blueprint for preventing the future rise of fascist states. Today, the European Convention and its Strasbourg Court play a vital part in shaping the rule of law in 47 European states, promoting free speech, fair trial and human dignity, especially in Turkey, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet territories. For the UK to withdraw from this successful system would be unthinkable.

Repealing the 1998 Human Rights Act (which made the Convention a part of UK law) would be otiose – cases would still be bought, by way of petition, to the European Court in Strasbourg although the process would take years. This would still be the case were the Coalition then to re-enact the Human Rights Act shorn of those few provisions that its Tory critics dislike – such as its absolute ban on torture, which prevents the deportation of terror suspects to states where they are likely to be killed or maimed. This kind of "British" Bill of Rights would be perceived as a squalid document, and would not even serve its vicious purpose since the Strasbourg Court would still require the UK to abide by the Convention, which would remain as a treaty obligation. For these reasons, the European Convention is here to stay.

Nevertheless, supporters of civil liberties like Nick Clegg must not turn a blind eye to its serious defects. It was a wonder for its time, but that time was the 1950s, since when the concept of human rights has considerably widened. Today it is astonishing to have a Bill of Rights that says nothing about the rights of children or the physically or mentally disabled. It is regrettable that it was incorporated into British law with one nasty little 1950s hangover, permitting the government to "impose restrictions on the political activity of aliens" (Article 16). It is silent on the subject of social and economic rights – to health or welfare services, to social security in the event of unemployment, to the right to join trade unions or to other rights which may soon become relevant in respect to this Government's cutbacks. There is no mention of the right so close to Con-Lib hearts, and certainly worn on Con-Lib sleeves, namely the right to a pristine and healthy environment.

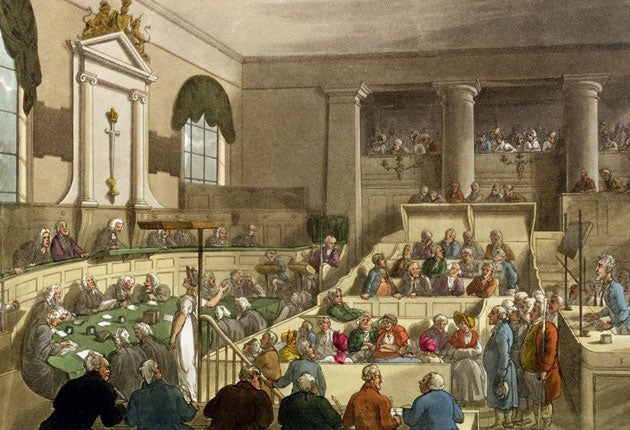

Another obvious defect is that the Convention only codifies rights that are "European". Thus, it offers no protection at all for trial by jury, abolished by Napoleon for most of the continent. It might be accounted the most basic constitutional right of a British citizen – and of an American and of citizens of many Commonwealth nations – not to be gaoled for more than a year without at least the option of being found "not guilty" by a jury of 12 good men and women and true. Yet for all the windy rhetoric we have invested in trial by jury ("the lamp that shows that freedom lives" – Lord Devlin) it has no protection from laws passed by panicked politicians: the first long prison sentences after a judge-only trial for armed robbery were imposed last month, and more non-jury trials for serious offences are in the pipeline.

The European Convention is, for the same Eurocentric reason, silent on rights achieved for Parliament by the civil war and the "glorious revolution" of 1689, such as absolute privilege for freedom of speech in parliamentary debates – infringed last year by the Trafigura "superinjunctions" and by the ignorant Speaker Martin when he permitted Scotland Yard to raid Damian Green's office in search of his source for statements made in the Commons. These and similar rights are fundamental to our concept of democracy and civil society, but they are missing from the European Convention. They need to be entrenched in a British Bill of Rights – not merely by a statute that can be overridden by later legislation, but in a written constitution which requires a referendum or at least a two-thirds majority in the Commons before its provisions can be altered. (Academics may say we have an "unwritten constitution" but this is a contradiction in terms: without an entrenched statute, no liberty in Britain is safe from the meddling of politicians.)

Another problem with the Euro Convention is that it was a compromise – a "lowest common denominator", where rights weakly protected in some countries had to be weakly protected in the Convention. Take, for example, the open justice principle – perhaps the greatest achievement of English common law, summed up by the aphorism that "justice must be seen to be done". Won by "Freeborn John" Lilburne at his treason trial in 1649, the rule was given philosophical shape by Bentham ("it keeps the judge, whilst trying, under trial") and practical force by Wigmore who pointed out how it deters perjury and encourages witnesses to come forward. In 1913 in Scott v Scott (the closest we have come to a constitutional case) the Law Lords declared that "every court in the land is open to every subject of the King". By 1950, under English law, only when justice could not be done at all was secrecy allowed – eg, to hide the identity of a blackmail victim. But the law in other European countries was very different: the Nazis in Germany prosecuted homosexuals and "moral defectives" in secret, and Scandinavian countries shielded defendants from publicity before – and sometimes after – their conviction. So the lowest common denominator compromise was chosen, hence the weasel words of Article 6 of the Euro Convention: "the press and public may be excluded from all or part of a trial in the interests of morals, public order ... or where the private life of the parties so requires." In 2005, the Law Lords disastrously decided the rule in Scott v Scott had been superseded by Article 6, and the result was an effervescence of anonymity orders, gag orders and secret proceedings. This is an example of how the Convention has damaged a freedom seen as fundamental and safe.

A further problem with the Convention is the weakness, in places, of its language. This can be illustrated by the plight of Gary McKinnon, the hacker with Asperger's, whose reckless genius enabled him to break into US Army computers to leave a message critical of Bush foreign policy – in the process he caused damage that he did not realise would amount to £350,000. Had he been prosecuted here, he would have been dealt with compassionately – probably by a suspended sentence. But the merciless elected State prosecutors of Virginia want to put him in prison to serve a sentence that our Courts estimate will be eight to 10 years. Such a punishment, for a man whose offence was driven by an undiagnosed mental disorder, would by our standards be described as "cruel and unusual" – contrary to the ban on disproportionate punishment in the 1689 Bill of Rights. But when parliament passed the Extradition Act in 2003, it rejected the language of the British Bill and chose instead to use the watered-down language of the European Convention: it gave the Home Secretary the power to stop extradition to the US only when the punishment would be "inhuman and degrading". Since American gaolers are not inhuman and their prisons are no more degrading than ours, the Courts have been unable to stop McKinnon's extradition for a punishment that does not fit the crime. The solution is not to alter the US/UK Extradition Treaty, but to make all such decisions amenable to the prerogative of mercy, whenever the end result would amount to cruelty. That would be part of a British Bill of Rights of which we could all be proud, rather than a weak-worded compromise.

The European Convention has been valuable in filling gaps in the common law, although its generalised, loose language has caused confusion and produced poorly reasoned judicial decisions from civil law judges in Strasbourg that have damaged freedom of speech in the UK. For example, the new Convention right to privacy has been useful in protecting from media exposure intimate personal details, eg, of medical treatment. But Strasbourg jurisprudence has become sprawling and incoherent on the subject of privacy, which it defines as "physical and psychological integrity ... there is a zone of interaction of a person with others, even in a public context, which may fall within the scope of private life". This psychobabble is now incorporated into our domestic law with the result that nobody writing a non-fiction book about the recent past can be safe from legal action if they reveal truthful details to which a public figure might take exception on the basis that it interferes with his psychological integrity or "zone of interaction with others".

Despite these inadequacies, there is ample evidence that the Human Rights Act has measurably improved the level of dignity and decency accorded by the state to its most-vulnerable citizens, and for that relief much thanks to the Blair government which enacted it with cross-party support in 1998. But it has not, as its proponents hoped, conduced to a "culture of liberty". They have blamed tabloid vilification, and timid and defensive Labour Ministers (Jack Straw's Green Paper last year about a "British Bill of Rights and Responsibilities" was pathetic and incoherent). But the main reason has been the continued perception that it is not rooted in the UK's history and experience. Its preamble is Euro-centric, Euro-prosaic, and Euro-dishonest, in the latter case by speaking of " countries which have a common heritage of political traditions, ideas, freedom and the rule of law". Should we recall common political traditions with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, or the ideals of Machiavelli, or the "freedom" left after lettres de cachet and the Code Napoleon, or the rule of law which prescribed torture as part of the continental legal process for centuries after it was abolished in England in 1641?

This is where the case for a British Bill of Rights becomes overwhelming. Not as an updated improvement on the Euro Convention but as a powerful symbol of British identity. A reminder to our children – and to our immigrants and indeed ourselves, of the struggles in this country to achieve democracy and its accoutrements – parliamentary sovereignty, judicial independence, press freedom, habeas corpus, trial by jury and so forth. We teach our children nothing about Lilburne and Milton and Wilkes, or about the Petition of Right or the 1689 Bill, or about Tom Paine and the brave booksellers who died in prison for selling The Age of Reason, or about Erskine and Bentham and the Tolpuddle Martyrs. The present GCSE syllabus pretends that the struggle for civil rights began in Mississippi in 1964, and not 320 years earlier at Naseby. What is needed is a Declaration that proudly recites our heritage and history of liberty, which will be immutable and enforceable.

David Cameron's offer of such a Bill was left out of the coalition compromise, and has now been referred to a committee. One that should include historians and authors and poets, as well as the inevitable lawyers and MPs. If they can put together a credible and inspiring draft, the Prime Minister should summon a national convention to debate it, followed by a referendum in which the people of this country could decide to entrench it as the first building block of a written constitution – unalterable except by a further referendum or a two-thirds vote in the Commons. If Messrs Clegg and Cameron can produce that kind of real change, they will truly have lived up to their campaign rhetoric.

Geoffrey Robertson QC is author of 'The Tyrannide Brief' and 'The Justice Game' (published by Vintage)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks