Scientists find leftovers from the universe’s very first stars

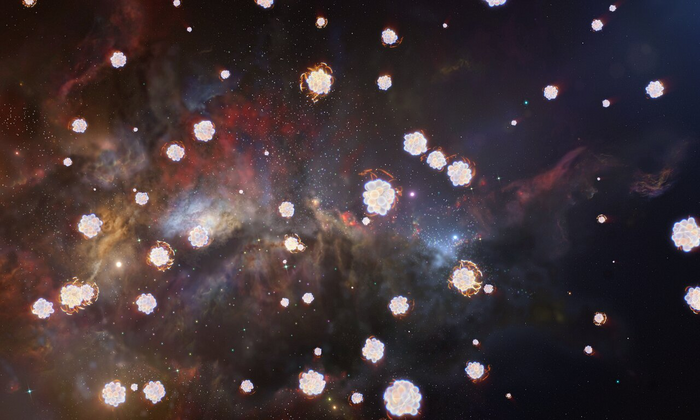

Astronomers have found the “fingerprints” of the explosions of the universe’s first stars.

The findings could give researchers a better view of what happened when the first stars formed after the Big Bang.

“For the first time ever, we were able to identify the chemical traces of the explosions of the first stars in very distant gas clouds,” said Andrea Saccardi, who led the study.

Scientists believe that when the first stars formed, 13.5 billion years ago, they would have been very different to those that surround us now. They were more simple, made of hydrogen and helium, and maybe hundreds of times bigger than our Sun.

Soon after they were born, they were thought to have died off in huge explosions named supernovae. That would have sent out heavier elements into the gas that surrounded them, which in turn would have gone on to create new stars and eject yet more heavy elements.

That process was key to creating the universe that surrounds us today. But scientists struggle to learn about them, since they have died off.

But researchers are able to better understand them by finding the chemical elements that were left behind when they died. Now, using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, researchers have done exactly that.

The three distant gas clouds seen by astronomers were around when the universe was just 10 or 15 per cent of its current age. They appear to be the leftovers of those ancient stars, scientists believe, based on the chemical fingerprint they left behind.

They spotted them by looking for quasars, bright emissions of light that are powered by supermassive black holes. As they travel through the universe they pick up signatures of the gases they have moved through, and scientists can see them using equipment on Earth.

Scientists hope the data on those leftovers can be used to better understand the first stars, and so give us a picture of how the universe went from simple elements to the powerful, complex stars that surround us today.

The findings are described in a new study, ‘Evidence of first stars-enriched gas in high-redshift absorbers’, published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks