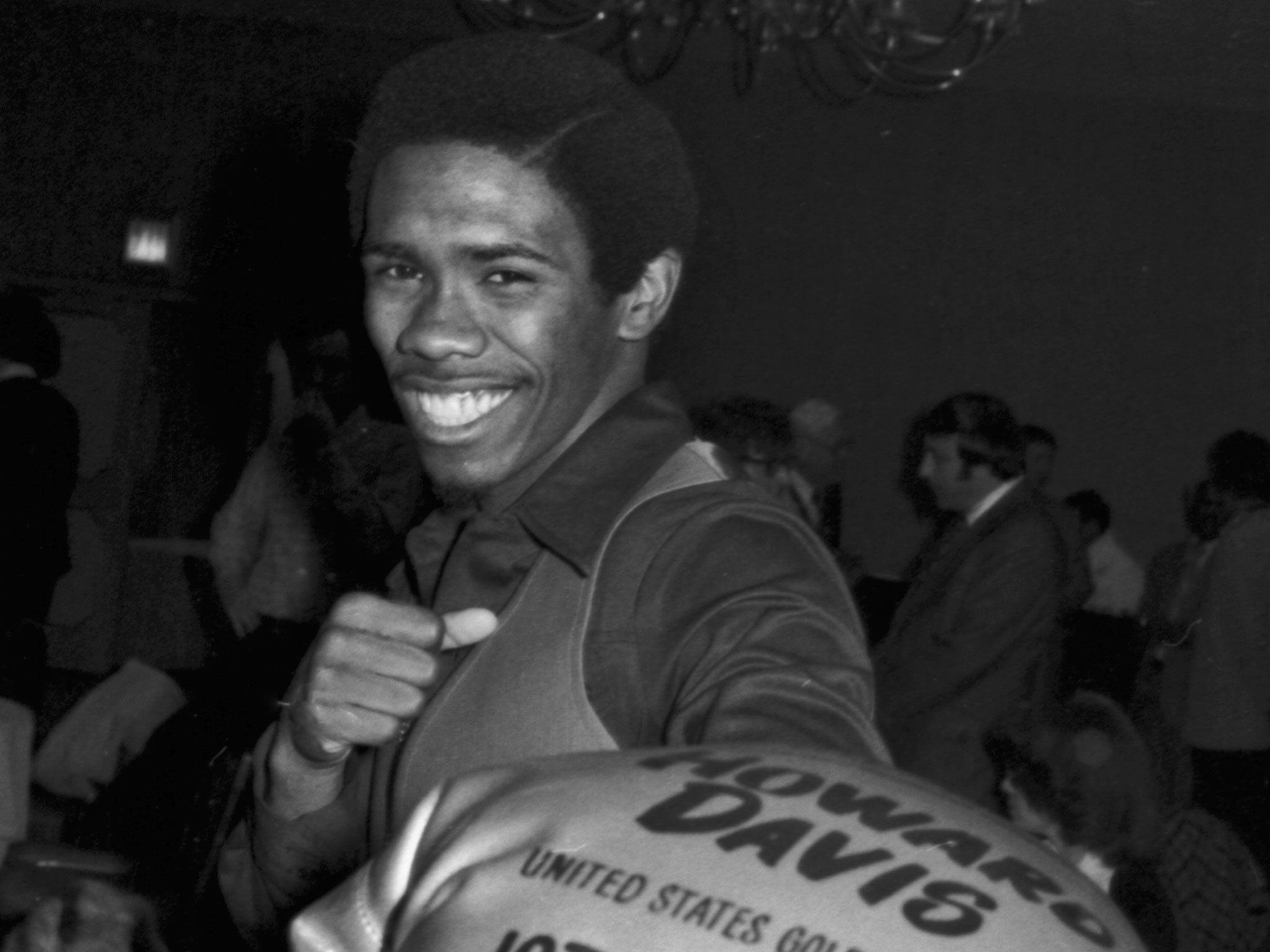

Howard Davis Jnr: Olympic gold medallist who was arguably the best ever US amateur boxer

The dazzling boy with the broken heart from the 1976 Olympics would miss out on a professional world title

Howard Davis Jnr was the breathless kid at the 1976 Olympics with the sad eyes, the beautiful hand speed and a head full of memories of his mother who had died three days before he started fighting for gold. Davis won the Val Barker trophy that summer in Montreal – an award for the finest boxer at the Olympics – and needed his friends Sugar Ray Leonard, Michael and Leon Spinks to persuade him not to leave the Olympic village when news of his mother’s death arrived. He was a commentator’s dream in Montreal, the dazzling boy with the broken heart, when the American boxers gained savage revenge over the Cubans and Soviets.

“I had no interest in boxing, I just ran and kept running,” admitted Davis, who was 20 at the Olympics but looked 12. “I just wanted to get away when I found out. They talked me into boxing, talked me into winning the gold for my mum.” Catherine Davis was 37 when her heart stopped; Howard was the eldest of her 10 children.

After the Olympics Davis signed a television deal that was better than any secured by either Leonard or the Spinks boys and their greedy handlers and advisers. Davis was being paid $185,000 for each of his fights, more than any gold medallist from London 2012 received. He was the star, not Leonard, not “Neon” Leon, and certainly not the shy Michael.

Mike Rappaport and Mike Jones, the men who managed Davis and were known as “the Wacko Twins” for their excesses, drafted in a boxing fixer called Johnny Bos to find suitable opponents for their man to fight. “He [Davis] never had a hard fight on the way up,” claimed Bos. “I had my orders: the opponents needed a pulse, but not much of a pulse.” Bos was the best in the business for protecting fighters.

In 1980, after 13 fights without loss, Davis was forced to travel to Glasgow to fight Jim Watt, a Rangers fan, at Ibrox in the wet and wind in front of just over 12,000 diehards for the WBC’s lightweight title. Watt retained over 15 dour rounds and Davis was criticised for his performance, which seems harsh considering how tough Watt was, how inexperienced Davis was, the location and the bad conditions.

“I would have beaten him if I had the right attitude,” said Davis. “I was depressed. I just didn’t want to be there.” He kept on winning fights, but by 1982 he had been overtaken by Leonard, the Spinks boys and even the fifth American gold medal winner, Leo Randolph. The quartet that he once led had all won professional world titles. In 1982 Davis was in dispute with Rappaport and Jones and his gold medal had been stolen; he was accused of walking away from lucrative fights or refusing fights and his future was in doubt. “He doesn’t want to fight. Howard never really wanted to fight,” Rappaport said at the time.

That is possibly true, but he was also brilliant to watch, a study in smart boxing, and he was, arguably, the best American amateur ever. He lost just five times in 130 amateur fights and in 1974 won the lightweight title at the inaugural world amateur championships in Havana, beating the feared Cubans and Soviets.

His critics were not as kind and David Wolf, the manager of potential opponent Ray Mancini, said: “Davis is a spoiled brat. He acts like a fool and handles his money like a moron.” Davis had made over $2m dollars by 1982, but had to ask his estranged managers for a loan of $5,000 that fateful year.

In 1984 he fought for the WBC world lightweight title again and this time he went to the truly hostile backyard of the unbeaten Edwin Rosario in Puerto Rico. Davis lost a split decision and would fight just once more for a world title, a brutal encounter one night in 1988 at the Felt Forum, the basement bearpit at Madison Square Garden. It was a brief and savage end to the high life for Davis and he was stopped by Buddy McGirt in round one.

“I came into boxing with the enthusiasm to conquer the world,” he recalled. “I told myself that I couldn’t die, I’m inhuman and I’m Superman. But you have to experience the disappointments. There’s no way to prepare for it.” In February 2015 Davis, who had moved from his native New York to Florida to run a boxing and mixed martial arts gym, was diagnosed with incurable late-stage lung cancer. He never smoked, never drank and never ate red meat. He received his terminal prognosis and started alternative therapy; he was an original thinker, and that is not always easy in the boxing business.

“It’s not about getting hit, it’s about not getting hit,” said Davis about the sport at which he became a reluctant genius. The sad-eyed boy from the glorious Montreal Olympics never had a lot of luck in the ring, or outside it. He was just a smart boxer, a dazzling technician and a fighter with more brain than brawn.

Howard Davis, boxer: born New York 14 February 1956; died 30 December 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies