Experiment fails to stand test of time

A triangular tournament held in England 100 years ago does not augur well for the ICC Championship

Test cricket is dying a slow death. The full, happy houses in England, as witnessed again this summer, are merely laughing in the face of disaster. Everyone connected with the game knows this and have solemnly pledged to do something about it.

Pledging and doing are different things, of course, and the favoured course of action, the World Test Championship, has been postponed by the International Cricket Council until 2017. Then, it has been pledged, solemnly, it will definitely take place. Time will tell.

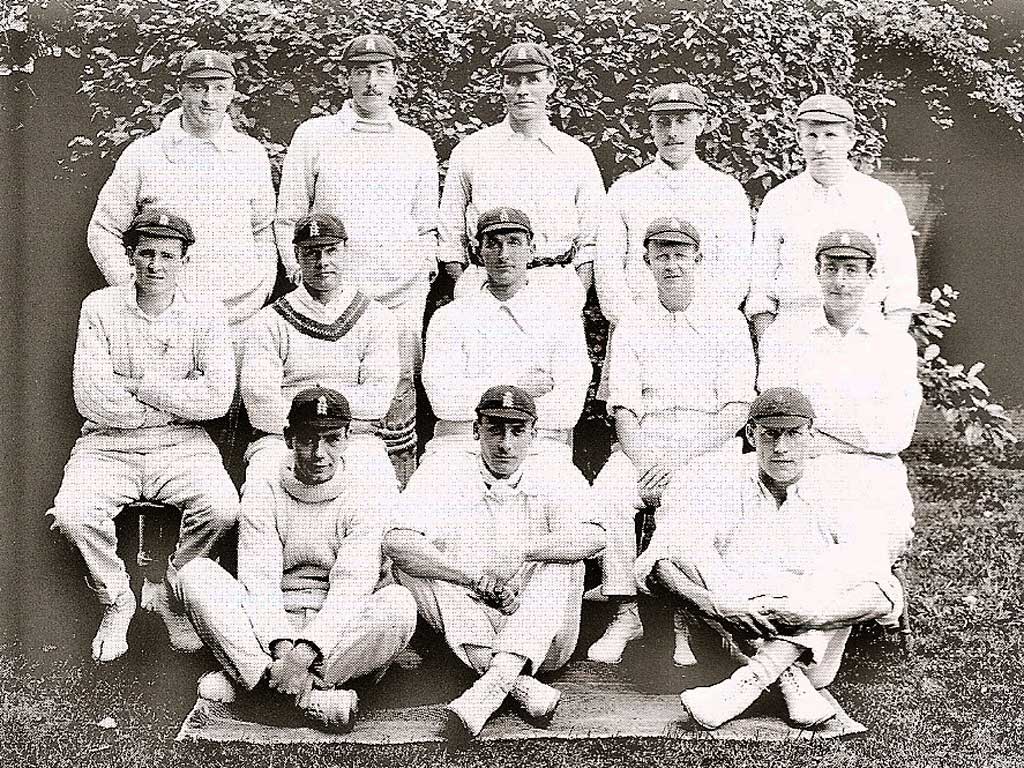

It may not, in any case, provide the succour that is so fervently desired. One hundred years ago today the first and so far only Triangular Test Tournament began in England. Australia played South Africa at Old Trafford. It had been five years in the making but here it was, at last, featuring the only teams that played Test cricket at the time, England, Australia and South Africa.

The tournament was the brainchild of a South African millionaire called Abe Bailey, a pioneering property magnate who was a henchman of the great Empire builder Cecil Rhodes. Bailey was cricket daft and had the money to do something about it, a forerunner of men such as Kerry Packer and Allen Stanford.

He first proposed the idea on a trip to England in 1907, stating: "Inter-rivalry within the Empire cannot fail to draw together in closer friendly interest all those many thousands of our kinsmen who regard cricket as our national sport, while secondly it would probably give a direct stimulus to amateurism."

It was immediately embraced by MCC, who were then lords of all they surveyed, and 1909 was the first year designated for it. But the administrators could not agree and by the time 1912 was alighted on, world cricket was in conflict.

The story of what transpired has been painstakingly assembled in Before the Lights Went Out by Patrick Ferriday. Somewhat inappositely, it was published last year but the lessons to be gleaned are timeless.

Nowhere was the turbulence in cricket at the start of 1912 more apparent than in Australia, where the board were involved in a power struggle with the players. It was to result in six of their leading cricketers not playing in the tournament.

The dispute was not helped by Australia being given the runaround by England in the 1911-12 series. With the conflict at its height the captain, Clem Hill, and his fellow selector Peter McAlister came to blows. "You've been looking for a bloody punch in the jaw all night," said the mild-mannered Hill, "and I'll give you one." There ensued a brawl lasting 20 minutes, after which they tended their injuries and sat down to pick a team. But there was no rapprochement and Australia sent a weakened side.

In South Africa there were also problems about availability. Abe Bailey might have resolved them with the flourish of a chequebook but as is the wont of rich men sometimes he kept it in his back pocket. It meant a South African team already past its brief peak sailed without its blue riband bowler, Ernie Vogler, a leg-break and googly merchant, and its preferred captain, Percy Sherwell, who claimed business commitments.

English cricket was run on autocratic lines then and CB Fry, without much recent form, was appointed as captain for the series because Lord Harris said he should be. Fry and the selectors met once before the series and not again for the whole summer.

Despite such a gestation period there were a few oversights in the organisation, not least how the winner should be arrived at. When at last it began on 27 May, it was to be blighted by bad weather throughout. South Africa turned out to be woeful.

The first Test on Whit Monday had a first-day attendance of 8,609, fewer than would have attended a county match. Yet the second day contained a unique feat. The Australia leg-spinner Jimmy Matthews took two hat-tricks 90 minutes apart, one in each of South Africa's innings.

But the competition failed to engage the public; South Africa managed only one draw in a rain-ravaged match and five defeats; England at least won the ninth and final Test against Australia when Fry was booed by the crowds at The Oval.

The total receipts were little more than £12,000, the touring players earning much less than they had in the golden age only a few years previously. Bailey said nothing. It was generally considered an abject failure.

The 100th anniversary of the Triangular Tournament coincides with the Test at Trent Bridge and the Indian Premier League Twenty20 final. It is not difficult to foretell, if gloomily and if we do not act quickly, where the future really lies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks