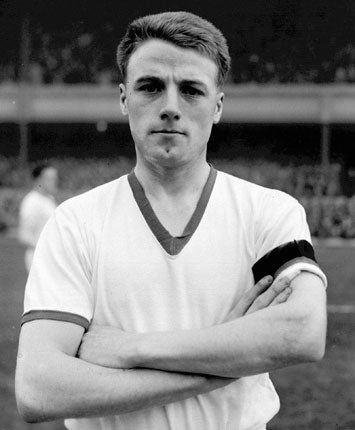

James Lawton: Sad end for a troubled survivor

Albert Scanlon, who died this week, lived through the Munich air crash. But part of the Busby Babe never recovered

Albert Scanlon survived Munich, at least in a manner of speaking he did. He spoke out of the corner of his mouth, like the heroes in the gangster films he so admired. No one ever heard him say that the horror of the plane crash had broken him, but many suspected in the long-run it had.

It had taken the best of his football talent. That emerged in the two seasons that followed his amazing recovery from a fractured skull and serious kidney damage.

And when they said it had indeed removed the best of the footballing skill it was saying a lot because if Munich hadn't happened there was a strong chance that he would have signed for another power in English football, Arsenal.

It was a gradual process, the slide from all that he might have been and for a little while it seemed that he had indeed taken the blows to both his body and his spirit and was able to remake himself. He left the Rechts der Isar Hospital with astonished doctors saying that he could indeed be physically whole again, within a year their improbable prognosis was proving correct.

He attacked along the left-wing with such bite and pure speed that he scored 16 goals in 1958-59, the season that followed the one which saw the team decimated, and he was a major reason why Manchester United confounded what was seen as a grimly inevitable decline with second place in the First Division. Not only did he appear to have survived, he was also flourishing.

But what the world did not see so clearly then was that something inside had indeed been broken.

Down the years it became increasingly apparent, though Scanlon, a wry and worldly product of the tough Manchester district of Hulme, never confessed to his pain or his sense that both his horizons and his circumstances had been terribly diminished.

This was the special poignancy that came with Scanlon's death this week, when he passed away at the age of 74 from the effects of kidney illness.

On the obituary pages of this newspaper, the details of a career that might have been something quite else, and which if it had unfolded in this decade would surely have left him in hugely better circumstances than the ones that accompanied his death, are traced thoroughly.

Yet the experience of Scanlon, his willingness to live with disappointment while not being consumed by bitterness, is in a way an account of a whole generation who never assumed the talent they had would ever be translated into a life of fabulous riches.

It meant that a man like Scanlon was obliged to live largely on his memories of how he was when he had reason to believe that his glory as a footballer stretched without foreseeable limits.

When he played his last game on British soil before Munich he was indeed occupying the centre of the football universe it seemed. He was the star of a United team which won a game 5-4 at Arsenal with such flair and exuberance the crowd at Highbury delivered a thunderous ovation that stretched into minutes, Scanlon had stolen the attention from such giants as Duncan Edwards and Bobby Charlton, and at one point he turned to the latter and said, "This is easy, isn't it?" And then they flew to Munich and nothing would ever be so easy again.

In 1997, Scanlon was among the United veterans who were invited to Munich to watch the European Cup final between Borussia Dortmund and Juventus. Charlton, Dennis Viollet, Jackie Blanchflower, Ray Wood, Kenny Morgans and Scanlon suffered in their different ways that day.

They were pleased to be in the city, which had helped to nurse them back to life, but they were hurting too and no one was more anguished than Scanlon.

He rarely let down his guard. He was a man who believed that you had to deal with what had been given to you and his style reflected the tough streets of places like Hulme and Salford, where he spent so much of his life.

But he admitted in Munich that he had suffered terribly on the flight out, had felt disturbed by the sweat that covered his face and the memories that plagued him. He returned by train, after enjoying the game, talking with his old friends and going back to the hospital. But there were scars too and they were livid at times in those 48 hours which had brought back the past so vividly. Charlton has always said that the pain of Munich, its meaning and the effect it had on its victims could never be quite quantified. Above all, he had insisted there has been the guilt of being among those who survived.

Of course survival can be a matter of degree and when Albert Scanlon died this week we could be sure that his feelings were more complicated than anything as basic as guilt.

Charlton went on to a superb career with both United and England, and if what happened in Munich would always be a part of him, it was in some ways a driving force, a strength, providing a need to prove that the fallen of Munich would not be forgotten and when a great victory came, as it did 10 years after the tragedy in the European Cup final against Benfica it would be in their memory and honour.

Scanlon had no such uplift, no such crusade, he had that one brilliant post-Munich season, he went to Newcastle and failed and then he played out his days in places like Lincoln and Mansfield.

Then there was a lifetime to imagine how everything might have been so different. That he spent it with humour and grace, that he never railed against the accident of time that had worked against him, left him impecunious while another generation of sometimes quite modest players were given a life of riches, is partly a tribute to his nature, partly a statement about how it was when a footballer was part of a world which more easily recognised that there were no guarantees, whatever your talent and your ambition.

As was a footballer whose best hopes were broken on one random, snow-filled night. But he was also a man who was ready to accept whatever was his fate. His epitaph is one shared by so many of his breed.

Albert Scanlon: Life and times

*Born in Hulme, Lancashire, in October 1935, Scanlon came through the Manchester United youth system, making his debut in 1954. He helped the club to titles in 1956 and 1957.

*At 22, he suffered a fractured skull and a broken leg in the Munich air disaster on 6 February 1958, but made a full recovery and was back in action in 1958-59, scoring 16 goals.

*After six seasons at United, he left to join Newcastle, and also represented Lincoln, Mansfield and Newport.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments