James Lawton: The Cup Final on Saturday night? We'd be better off putting the grand old thing out of its misery

Crawley Town, God bless them, have their date with football history today at Old Trafford and tomorrow Orient and Notts County go against the class and the wealth (as always, they are not necessarily the same thing) of Arsenal and Manchester City.

Who knows, we might just get an echo or two from the past, the kind of deathless glory that came to the likes of Yeovil Town, Walthamstow Avenue and Hereford United back in earlier football ages.

We might have a 24-hour sensation, something to nudge the bellyaching reflections of some disenchanted superstar off the back pages. We might have another version of the giant-killer's story, the one that so enrages some old pros who ask why the little guys are allowed to get so uppity on the rare days they do something right.

Sadly, though, we should not be deluded enough to believe that the FA Cup's long decline is anything but a terminal condition.

A bout of remission here, a flash of defiance there, sure, but the big picture is so full of the detail of human fecklessness it might have been painted by Hieronymus Bosch.

It portrays the indisputable and irredeemable fact that the FA Cup, which stood for so much that was fundamental to the joy of sport, has been diminished systematically by a combination of greed and indifference.

The latest threats, which understandably enough are filling the Football Association with foreboding about what is left of the future of what used to be their flagship property, are proposals to stage the final on the same day as a potentially key Premier League game – and for the benefit entirely of the paymaster TV and its viewing figures, on a Saturday night.

This is a nice plump little morsel to occupy time normally devoted to pre-lottery quiz games and the banalities of celebrity ballroom dancing but whatever else we feel about the fate of the old Cup in a changing world and evolving priorities we can surely say it deserves a hell of lot better than this.

It should either be respected for all that it has contributed to the national life, and preserved a little more fastidiously, or lined up against the wall and put out of its misery.

Another plan – because of the sheer weight of the Premier League and European schedules – is to dispense with replays – one of the absolutely pivotal aspects of the great tournament's appeal. The powerbrokers of football have decided that the idea of a replay – like the one in which Ronnie Radford dredged up the dreadnought shot from the muddy field of Edgar Street, Hereford, to knock out Newcastle United – can simply no longer be accommodated. A replay, however beautifully poised, however life-sustaining for the finances of a Burton or a Yeading or a Stevenage, is simply not worth the trouble. It is too time-consuming, too inconvenient and, when you look at recent crowd figures, not enough guaranteed financial reward.

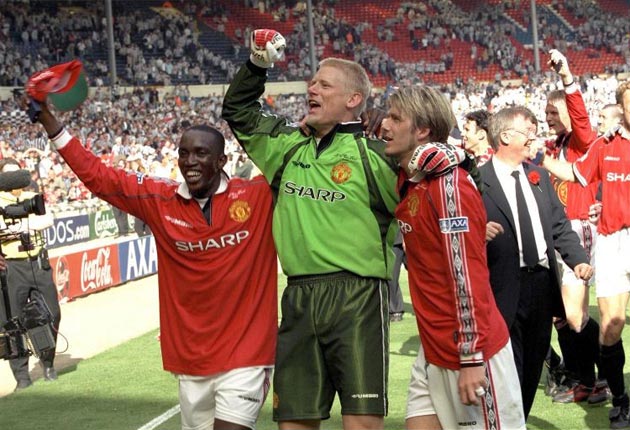

The landmarks of the Cup's death as a potent national institution are easy enough to chart. Far and away the most symbolic is the one of 2000, when Manchester United shamefully acceded to suggestions from the FA and the then sports minister that they should not defend the trophy that was the third string of their historic treble of 1999.

The message was that by instead supporting Fifa's cockamamy, catch-penny world club championship in South America they would be striking a big blow for England's failing campaign to stage the 2006 World Cup. In some quarters this initiative was seen as good, even statesmanlike politics. It was of course nothing less than an abject betrayal of a cornerstone of the national game.

That was not the first example as teamsheets for FA Cup games increasingly reflected the convenience of the big clubs still involved in the tournament. If they were out of title or European contention, and not desperate to avoid relegation, of course they would field strong teams. It wasn't so much the pursuit of glory but a payment on an insurance policy that might just pay out.

Arsène Wenger was no doubt expressing a blunt truth when he declared that winning the FA Cup was no longer as important as finishing fourth in the league and qualifying for Europe. But the decision of United not to defend made the new status of the FA Cup official. It had changed from a staple of the English game to a take-it-or-leave it luxury and if there was any doubt about this it was confirmed when United won their eleventh final – more than any rivals – by beating Millwall 3-0 at the Millennium Stadium four years after their South American misadventure.

On their way to the final Millwall defeated Tranmere Rovers, who had been unlikely sixth-round opponents only if you hadn't noticed that on their way they had beaten Bolton Wanderers reserves.

Maybe we shouldn't be too officious in our pursuit of villains. Perhaps the lingering death of the FA Cup has been dictated as much by circumstances as malevolence. The Stanley Matthews final, arguably one of the most compellingly suspenseful events in the history of English football, happened in another age, as did the Hereford eruption two decades later, and maybe we should accept the inevitability of changing values and interest.

Yet there is one legitimate point of anger. It is not so much in the demotion of the Cup in football's pecking order but the way it is from time to time dragged out, like some battered family heirloom, and dressed up as something it used to be.

It isn't. Shortly, we understand, it is likely to be Saturday night TV fodder, down there with the dance moves of Ann Widdecombe and John Sergeant. The old Cup that used to cheer deserves a finer interment.

Profit over people for Olympics and Champions League

No doubt £176 for a Champions League final ticket at Wembley sails into the gouging category but then the London Olympics have not exactly struck an unequivocal blow for accessible sport for ordinary people.

It will cost up to £725 to see Usain Bolt hit his ultimate stride for appreciably less than 10 seconds and if you want an intimate view of the opening ceremony pageantry you have to part with more than £2,000.

Lord Coe patiently explains that a Solomonesque compromise has been reached. Ticket sales are designed both to make the Games open to the men and women in the street, including the financially embattled ones who live around the East End Olympic Park, and provide a vital revenue stream.

We can be sure, though, of two things. If there is ever a conflict of motivation in modern sport the one of profit will always sail through. The Olympics, like the World Cup which in South Africa last summer priced out so many of the local population, are supremely about money. It just means that when you get to stage one you have to pay twice. Once in your tax – and then when you want to see something more riveting than beach volleyball.

No shame in saying sorry to Arsène

Yesterday it was suggested here that Arsenal manager Arsène Wenger had declared that Barcelona, his team's victims in a superb Champions League game on Wednesday, were the best team in football history. This was not correct, he merely, if rather coyly, said they were the best team that he had faced in his career.

Since Wenger's career as one of football's foremost intellectuals probably started in his toddling days, and that he was 21 when the fabulous Brazil won the 1970 World Cup and much older when the Milan teams of Baresi, Gullit and Van Basten were on the march to three European titles, some may feel his statement was a little disingenuous.

However, I was wrong and it is no hardship apologising to a great football man.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies