Kevin Garside: St George's day will come only if England players learn to love the ball

The Ballon d’Or shortlist reflects the influence of Spain’s greatest export

Tomorrow a door opens on English football's future. The Football Association cuts the ribbon on its new headquarters at St George's Park. There will be no parachuting in of the Queen but the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge will be there to mark what we hope is a departure.

The national side is also in action on Friday in a World Cup qualifier against San Marino, to whom a representative side from the football dark ages, AKA the 1970s, could still administer defeat. Poland next Tuesday is a stiffer test and, like the Ukraine experience of last month, a better measure of England's standing than the Fifa ranking which has them at No 5 in the world.

The St George's Park initiative acknowledges the need for football's mother country to fall into step with best practice elsewhere. The deficit is felt most keenly in the standard of grassroots coaching, an area in which England have fallen way behind our continental counterparts. In number and method, coaching away from centres of excellence at elite professional clubs has not been a priority. As a nation we have trusted in the idea that talent will somehow make itself known, force its way to the forefront of the game.

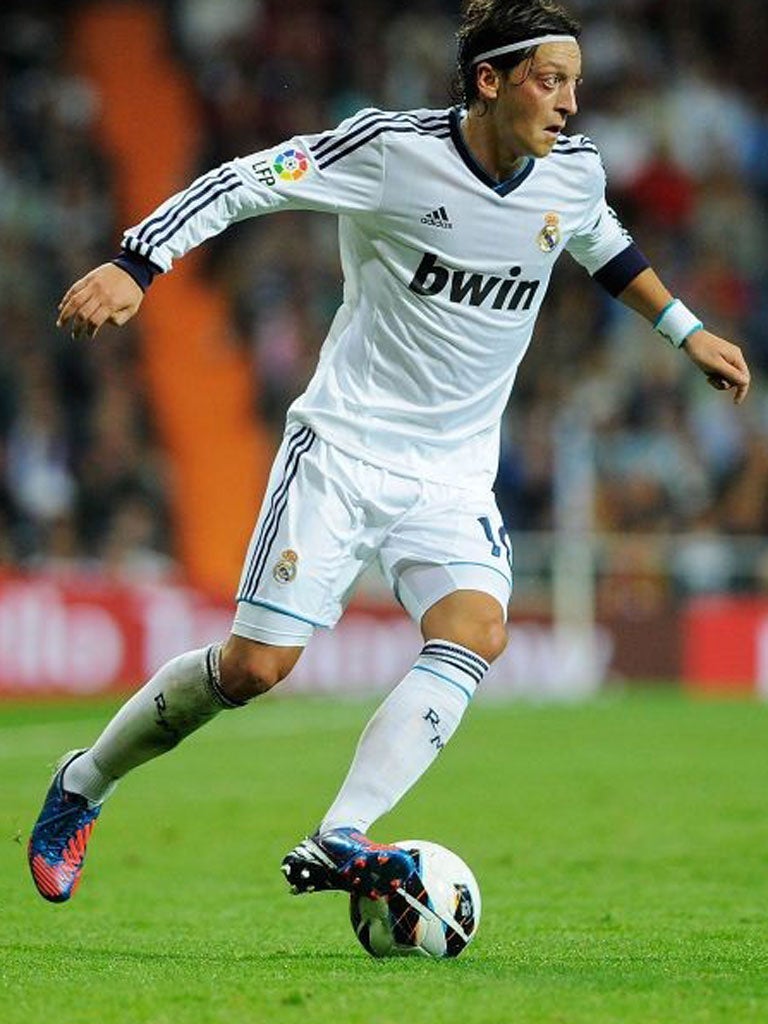

That idea is smashed by statistics revealed before the last World Cup in 2010 which showed a paltry 2,769 Uefa-licensed coaches at work in England servicing a playing public numbering more than 2 million. That is one coach per 812 kids. World and European champions Spain had 24,000 coaches, Italy 29,000-plus and perennial contenders Germany more than 34,000. The scales fall from the eyes, allowing us to make the link between grassroots footballing education and the emergence of skilful players of the calibre of Mezut Özil, Mario Götze, Marko Marin and Marco Reus in Germany and AN Other in Spain.

In three weeks' time, the shortlist for the Ballon d'Or is announced. The presence of Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, Xavi and Andres Iniesta is a given. All four shared the same pitch in the first Clasico of the season last night. The latter are Spanish, another, Messi, learned the game in Spain and the fourth, Ronaldo, grew up in Funchal immersed in the myth of Real Madrid. This Spanish eulogy reflects the growing influence of Spain's greatest export: its football. The domination of Barcelona and the attempts by Real Madrid to counter it are shaping the game, and not just in Spain.

No great team in history has dominated matches against other important clubs in the way Barcelona achieved under the Pep Guardiola regime. At the Barcelona finishing school, La Masia Academy, anything less than 70 per cent possession is punishable by a week's exile in Madrid reciting poetry in Castilian. This love of the ball and the trophies it yields has won an important argument. The most efficient way to beat the opposition in this method is by retaining the ball, which requires improved movement, greater positional fluidity, which in turn facilitates the rapid transfer of the ball – "quick ball" as they call it in rugby – between feet willing to receive it in any position.

A cursory glance across the Premier League demonstrates how this idea has already started to spread beyond the obvious powerhouses that traditionally contest the title. Everton have been transformed by the gradual retreat from the long-ball philosophy initially adopted by David Moyes, a former disciple of the damaging idea that Everton did not have the type of footballer capable of playing the Barcelona way. That notion is shredded by the present Goodison template that has thrust Everton not only up the league but higher in the table of aesthetics.

Sunderland were a revelation to these eyes despite losing to Manchester City on Saturday lunchtime. Martin O'Neill has frustrated in the past by adopting methods that bear an inverse relationship to his intelligent analysis. Though he is always a fantastic fireside companion with whom to discuss the finer virtues of the game, his teams have too often failed to reflect the subtlety of his thinking. His Aston Villa team was characterised by four big lads at the back and a big lump up front surrounded by nippy aides whose job it was to feed off scraps. In other words, the classic old-school template which sought to transfer the ball forwards as quickly as possible.

Route One was never the default response at the Etihad Stadium, even when under pressure. Sunderland kept the ball on the deck and, as a result, for much of the first half enjoyed chunks of possession that on another day might have produced a more profitable outcome. At Goodison Park and the Stadium of Light, at the Hawthorns and the Liberty Stadium (where Spanish golfer Sergio Garcia sat in the dugout on Saturday) the game appears to be engaged in a radical shift. They are a long way from being Barcelona, but that is not necessarily the goal. The point is to be the best they can be.

Keeping the ball is central to that. This requires a change in habits, particularly at grassroots level, which brings us to the doors of St George's Park, where the vision for a new England is enshrined tomorrow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments