No-one likes them, they don't care ... why are Bayern hated so much?

Super successful but dogged by decades of jealousy and hostility, the European giants remain unapologetic because they are 'a club apart from Germany'

The newly wealthy blue half of Manchester is becoming fully accustomed to the disapproval of domestic rivals, but their opponents tonight, Bayern Munich, are past masters at carrying on, and succeeding, regardless of others' jealousy and hatred. By far the most widely supported club in Germany and easily the nation's most recognisable football brand, Bayern are light years away from the cuddly international reputation of the Bundesliga today; as a wallet-friendly fan utopia, a football carnival that is a triumph of fun ahead of finance. They are a club apart, and defiantly unapologetic for being so.

The reasoning behind Bayern's deep unpopularity outside their own support is complex, particularly when one considers that their extraordinary success in the past 40 years or so was not authored by a sugar daddy. Their first Bundesliga title was won as recently as 1969 and 20 more have followed since, but the first great Bayern sides were built on a base of locally-bred youngsters, such as Franz Beckenbauer, Paul Breitner and current club president Uli Hoeness. It is more than mere jealousy of success; their arch-rivals in the 1970s, Borussia Mönchengladbach, actually won four titles to Bayern's three while remaining the neutrals' choice during the decade that nevertheless helped to definitively shape enduring stereotypes.

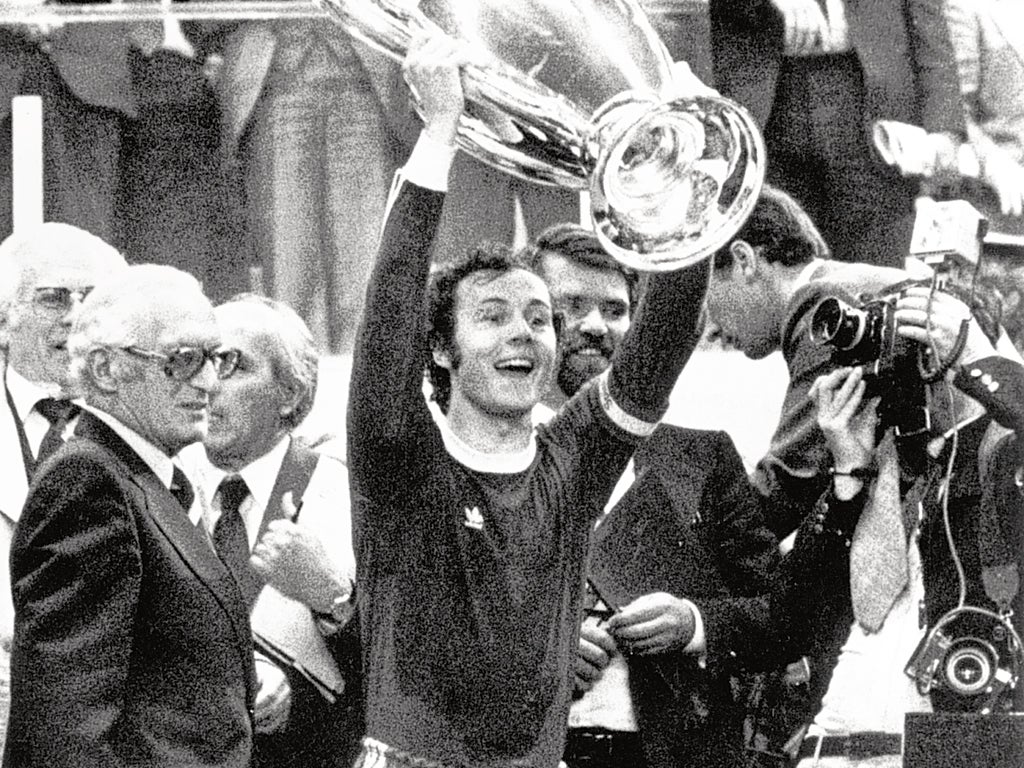

In Europe, the perception of a dastardly, unfathomable dark force was further perpetuated by the run of three consecutive European titles between 1974 and 1976. Hans-Georg Schwarzenbeck's equaliser in the final minute of extra-time saved the Germans from defeat to Atletico Madrid in Brussels in 1974, before they cantered home in the replay two days later. What appeared to be an opening goal for Leeds United's Peter Lorimer the following year in Paris was ruled out, after Beckenbauer persuaded referee Michel Kitabdjian to consult with his linesman for offside, leading to an outbreak of violence on the terraces. Bayern went on to win 2-0 after the ensuing stoppage. For the 1976 final in Glasgow, French champions St Etienne hit the woodwork twice (to this day, their fans lament the square goalposts and crossbar of Hampden Park) and Franz Roth hit the winner from a free-kick.

The balance of this prevailing image remains unaddressed, eliciting the considerable schadenfreude that met Bayern's dramatic cave-in to Manchester United in the closing minutes of the 1999 final. This was the middle one of three Bayern final chokes since their '70s heyday, sandwiched by the 1987 defeat by Porto in Vienna and 2010's loss to José Mourinho's Inter, though a fourth title was secured against Valencia, on penalties, in Milan in 2001. Bayern's success largely originates from prudent housekeeping, going back to the genesis of their most celebrated sides at the end of the 1960s, and continued into the following decade by the club's successful commercial exploitation of the 80,000-capacity Olympiastadion, built for the 1972 Olympics. If praise has been in short supply, it is at least partly because sensible financial management is not remotely sexy. In his book Tor! The Story of German Football, Uli Hesse wrote: "Put simply: Bayern were smart. And smart people who plan ahead, expect to be successful and have luck to boot, are seldom loved."

Still, City would give a fair portion of their considerable riches for a future Champions League record to mirror Bayern's. The four-time winners are second in Uefa's all-time European Champions Club's Cup ranking list, behind only Real Madrid. The shortcomings that saw Louis van Gaal's highly entertaining double winners eventually run aground in the 2010 final in the Spanish capital against Internazionale were neglected in the aftermath, and Bayern were outsmarted as well as outclassed by Jürgen Klopp's stylish league champions Borussia Dortmund last campaign, but things have changed under returning coach Jupp Heynckes, a stalwart of Mönchengladbach's own '70s glory years as a player.

Another enduring cliché, last season's notoriously haphazard backline, is being put to bed, with one goal being conceded in 11 competitive outings this season – to Mönchengladbach's Igor De Camargo in an opening-day defeat at the Allianz Arena. De Camargo's smash-and-grab winner followed a dreadful error by Bayern's Germany goalkeeper Manuel Neuer, signed from Schalke as a long-needed replacement for Oliver Kahn. Unfortunately, the 25-year-old had already antagonised a vocal proportion of Bayern's support having previously poked fun at the legendary Kahn, and was quickly issued with a list of "rules" by the Bayern ultras, which included not kissing the club badge or starting fan chants through a megaphone.

Neuer is now beginning to settle with the luxury of a much-improved unit in front of him and had little to do on a tense return to Schalke last week, as Bayern coasted home 2-0. Besides the installation of former City defender Jerome Boateng, the arrival of Brazilian right-back Rafinha has allowed skipper Philipp Lahm to cross back over to his preferred left-back slot. In turn, Lahm's repositioning has freed up the makeshift left-back of late last term, Luiz Gustavo, to return to his natural midfield role. From there, Gustavo scored the last-gasp winner at Wolfsburg in week two that got Bayern's season rolling. Further forward, the promotion of Toni Kroos has lessened Bayern's reliance on the sparkling but fragile pair of Arjen Robben and Franck Ribéry.

Ribéry puts his own return to form down to the return of Heynckes, which has "delighted" him. "It's no secret that Louis van Gaal and I didn't get on," he said. "I'm feeling mentally free again and really enjoying my football." His comeback from well-publicised personal problems and a catalogue of injuries has helped too. Bayern stood by the Frenchman, handed him a new contract, and finally appear to be getting their pay-off. Despite Heynckes recently hailing the "settled" Ribéry as "world-class", don't expect Bayern to get too touchy-feely – it's hardly a likely prospect under the power axis of Hoeness and chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge.

After driving a period of unprecedented commercial growth as general manager – culminating in the opening of the Allianz – Hoeness moved aside and into the presidency last year, to be replaced by the younger Christian Nerlinger. Chairman Rummenigge is also chairman of the European Club Association, and thus synonymous with the threat of an eventual European Super League, as the top clubs' discontent with Fifa grows. Bayern see themselves as an entity apart from the rest of Germany, and can accept any resulting hostility. Who needs love when you've got a masterplan?

Show us your medals

Bayern Munich are one of the most successful clubs in the history of the European Cup, more so than Manchester United, having won it four times.

* Real Madrid (9)

* Milan (7)

* Liverpool (5)

* Bayern Munich (4) Barcelona (4); Ajax (4)

* Internazionale (3); Man Utd (3)

* Benfica (2); Nottingham Forest (2); Porto (2); Juventus (2)

Bayern are one of the few clubs to have won the trophy three times in succession, dominating the mid-1970s, when Franz Beckenbauer ruled supreme. Only Real Madrid (1956-60) and Ajax (1971-73) have also won three consecutive European Cups

* Three of a kind for Bayern:

1974 Beat Atletico Madrid 4-0 in a replay after the first match ended 1-1.

1975 Beat Leeds United 2-0 in Paris.

1976 Beat Saint-Étienne 1-0 at Hampden Park.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments