There's help available for Kenny Sansom – but first he has to be ready to help himself

Kenny Sansom could put a date on the first time he got blind drunk: 30 May 1981, at the age of 22 and 18 caps into his England career. His errant father, George, had turned up out of the blue to watch him play for England against Switzerland in Basel and afterwards had thrust a glass of Buck’s Fizz into his son’s hand and then another and another.

That night in Basel he threw up in a taxi but even so, when he woke up the following morning, he decided that his days of ordering orange juice on team nights out were over. “When you play football and are surrounded by blokes who like to down pints of lager and laugh louder than their sober counterparts, it seems the right thing to do to join in the fun,” Sansom wrote in his 2007 autobiography. “It stops the feeling of being an outsider.”

It was an indication of how much his life changed at Arsenal that his nickname at the club became, for obvious reasons, “Mr Chablis”.

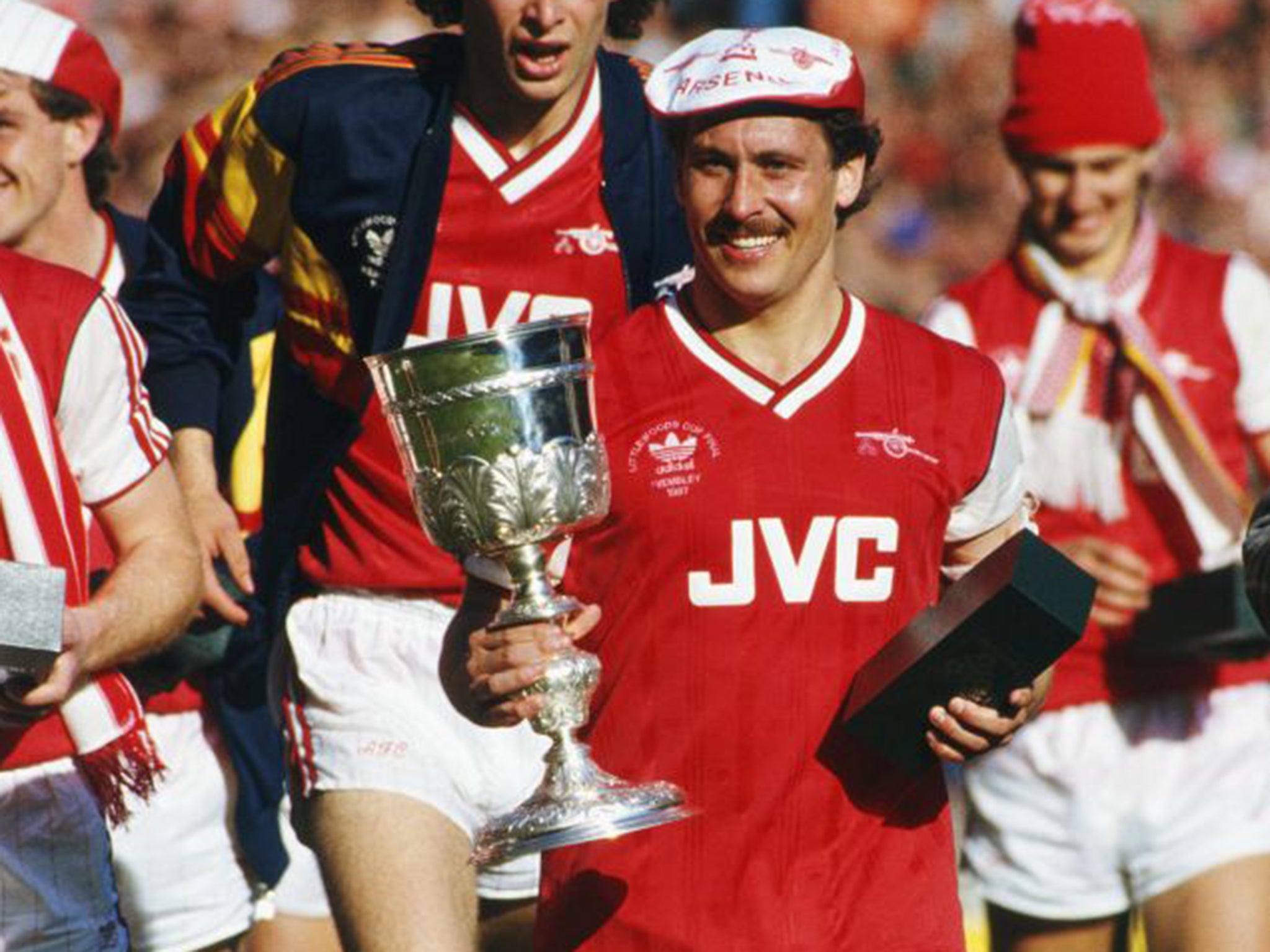

Even so, it is incredible to think that the man pictured in the Sunday Mirror this weekend, necking Mateus Rosé from a bottle and subsequently passed out in a south London park was virtually teetotal until the age of 22. This man with matted hair and bleary eyes was “Handsome Sansom” that brick of a left-back from a council estate in Elephant and Castle who became Arsenal captain and won 86 caps for his country.

“I got no house. I got no car. I got no life. I got no partner,” he told the newspaper. “It’s a horrible life I’m living at the minute.”

This week the Professional Footballers’ Association’s head of player welfare, Michael Bennett, a former player himself at Charlton and Wimbledon among others, will try to get Sansom into the Sporting Chance clinic founded by Tony Adams. Sansom has been there before – in fact, his 2007 book ends with a description of his first stay, and there is no one other than Sansom who can take the first steps to ending his two addictions.

Bennett has been working on Sansom’s case for the last three years and the PFA was already well aware that the 56-year-old was approaching rock bottom once again. The pictures that emerged this weekend were shocking but they are only a fraction of what the PFA deals with, as the only organisation supporting former footballers with addiction and mental issues.

Bennett is responsible for all those cases and, last year alone, the PFA was contacted by 197 of its members seeking support. That is some caseload for Bennett, a man who talks in the careful, measured tones of someone used to dealing with problems that must seem intractable. Last year, the PFA established a 24-hour telephone helpline for members. Safe to say, it is not underused.

Beyond that there is a 12-year partnership set up with the Sporting Chance clinic, established by Adams and the late Peter Kay, and a network of 60 counsellors across the country to whom PFA members are referred as a first port of call. The residential base that the PFA has access to has four full-time places on it, and there is a waiting list.

The problem, as Bennett sees it, is that the elite-level game prepares footballers physically but not emotionally. “What we realise is players often don’t get asked how they are,” he says. “They get asked about football. When they get asked about their emotions, they tend to open up.”

Bennett’s priority is that, having asked players to be open about their emotions, the PFA is now able to deal with those who come forward. As for Sansom himself, the PFA has reached a point now where the gambling and the alcoholism are setting one another off.

“We are trying to support Kenny and work through the issues and find out the root issue,” Bennett said. “We want Kenny to be into the process as well. We need the individual to express his problems. If he does we are halfway there. We will always support him. We are trying at the minute to get him a detox programme and then we can work with him.”

That is the essence of Sansom’s problem: there is very little that can be done to help him with the basics of a house and a job until he has stopped drinking. Arsenal, the club with whom he is most closely connected, gave him work leading tours of the Emirates Stadium but that ceased a year ago when he was no longer able to carry on. Beyond that they tried to point him in the direction of the help they thought he needed.

At the Football Association, where Sansom was an England youth captain before going on to make his senior debut at 20, and play at the 1982 and 1986 World Cup finals, the issue is the same. There is not much it can do until the man himself is sober. The FA contributed money on a one-off basis to Gary Mabbutt’s recent fund to put Paul Gascoigne into rehabilitation but it cannot do the same for every former international.

Bennett worked through Saturday and Sunday to try to find somewhere for Sansom to stay and there will always be more to do. It makes no difference that Sansom missed out on the salad days of the Premier League, he was, by his own admission, very well paid relative to the average salaried worker in the 1980s. His saving grace is that his trade union is unusual in that every footballer is a member of the PFA for life and his monthly £622 PFA pension has become his only income.

Sansom was born in a south London prefab in 1958, and his father abandoned the family not long after. George Sansom, Kenny later wrote, was “one of the original spivs” who was around the fringes of the London underworld of the 1960s but “too much of a coward to do anything bad”. George was so often absent that he did not even help name his second son. “Kenny” was a suggestion of his older brother, Peter. “I have no memories of young fatherly love,” Sansom wrote, “[or] any fatherly love to be honest.”

Brought up by a strong, loving mother, it is nevertheless not hard to spot the potential fragility of the young prodigy when you flick through the pages of Sansom’s book. When I mention that to Bennett, his reply is calm but forceful. “Yes, that might be so, but it’s a case of ‘Kenny, you’re 56 now. You can’t use excuses’.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies