An attempt at deciphering the genius of Manchester City's Kevin De Bruyne

Jonathan Liew tries to break down how the Belgian saw the pass for Raheem Sterling's goal against Stoke City on Saturday

I’ve been watching Kevin De Bruyne’s pass to Leroy Sane for several hours now, and I’m still trying to work out how he manages it. It wasn’t even an assist - it was the assist for an assist, for Manchester City’s second goal in the 7-2 win against Stoke last Saturday. Raheem Sterling scored the goal, but in a sense that was the least interesting part of the whole process.

So first of all I’m going to explain what happens, and then we’re going to try and make sense of it.

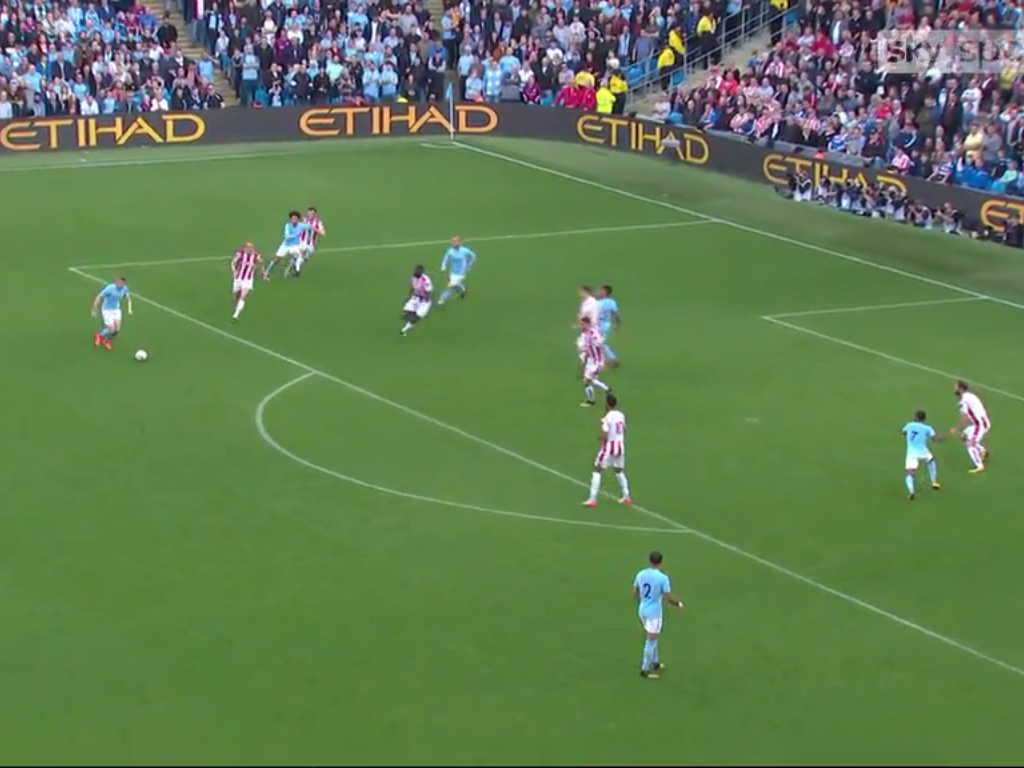

The situation is this: Manchester City have just taken the lead and are straight back on the attack. Sane has the ball on the left byline (figure 1). He thinks about a cross, decides against it, and instead retreats (figure 2) before laying it back to De Bruyne.

De Bruyne is about 20 yards out on the angle, halfway between the corner of the area and the edge of the D. As he receives the pass, his body is facing forwards, in the direction of Sane (figure 3). It is the last time De Bruyne will see him. Remember that bit: it’s important.

For in taking a touch (figure 4), De Bruyne swivels 90 degrees to the right, opening himself up for a shot, a cross or a sideways pass. Meanwhile, Sane has doubled back on himself and is now hurtling towards the byline again. De Bruyne can’t see this, because - to reiterate - he’s facing in the wrong direction.

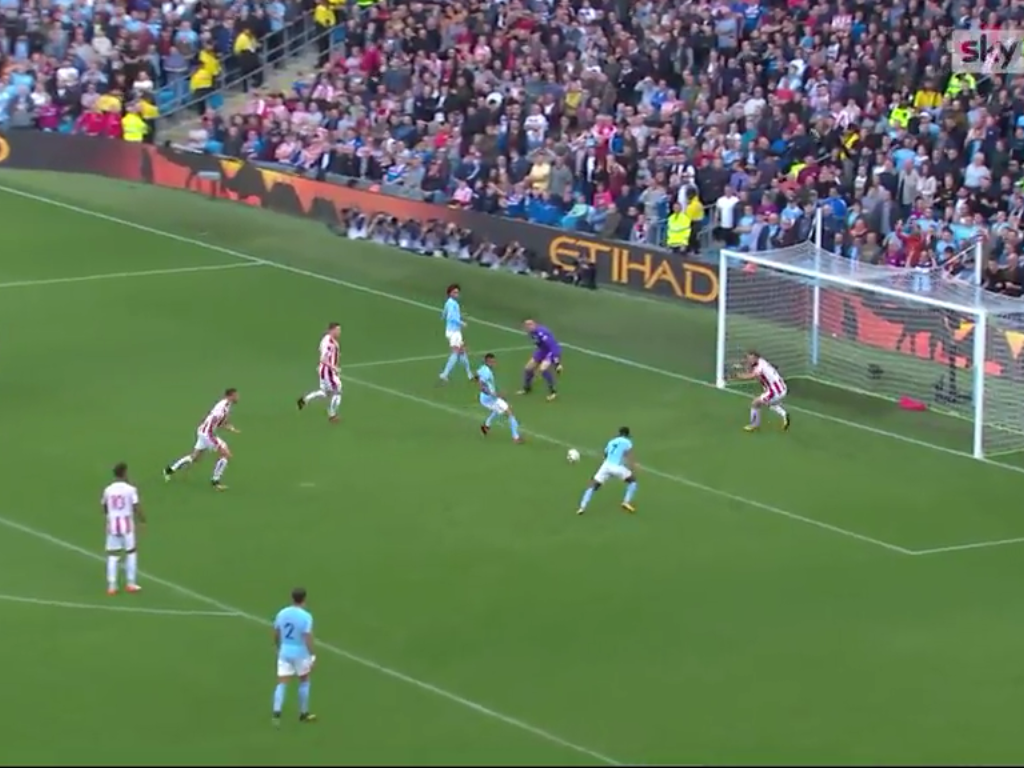

But somehow, at the very last moment, his right boot sweeps around the side of the ball (figure 5), nudging it past his left ankle. His knees are bent unusually deeply. His arms are out a little for balance. The ball fizzes in between the stationary Gabriel Jesus and David Silva, into the path of Sane (figure 6).

With one pass, De Bruyne has taken five Stoke defenders out of the game. Sane squares the ball for Sterling, who scores (figure 7).

If you watch the pass from another angle, from behind the goal, it becomes even clearer. De Bruyne turns away from Sane before Sane begins his run, and does not lift his head again until after the pass is played. There’s no way he could have seen Sane running.

And so, the crux: how did De Bruyne know to do that? To my mind, there are three possibilities here, which we’ll consider in turn.

The first theory, we’ll call the Penicillin Theory. As we all know, in 1928 Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin by accident when he was actually trying to make salad dressing, or something, and remained unaware of its significance for many years afterwards. Likewise, there’s a possibility that De Bruyne didn’t mean to pass the ball to Sane at all. Jesus is in his eyeline. Silva may just be visible in his peripheral field. De Bruyne may simply have been trying to slip the ball to one of them, and got lucky. We can’t rule it out.

The second theory, we’ll call the Batting Theory. About two decades ago, in his book A Test of Cricket, the former England batsman Michael Atherton wrote about the art of running between the wickets. For those unfamiliar with cricket: when the ball is hit, one of the two batsmen will make a call to determine whether they run or not. “Yes” means run. “No” means stay where you are. So far, so elementary.

But over time, Atherton began to notice a rare and curious phenomenon. With certain players - players he had been batting with for years and years - they gradually stopped calling altogether. Such was the instinctive and organic understanding between the pair that often, a quick glance was all they needed to know when to run, and when to stay put.

Occasionally, you suspect, the same process occurs in football. Sometimes you’ll see a player make a pass, and then point to where he wants the return ball played. But Sane doesn’t do this. Maybe, over the course of hundreds of small-sided training games, hours and hours of shadow play, months and months of conditioning, he and De Bruyne have developed their understanding to the extent that De Bruyne is now able to pick up on the subtlest of visual cues - a look in Sane’s eyes, the shape of his body, a right foot just a little wider than usual. Something that told him Sane was about to make that run into the left channel.

If that’s the case, then it’s a tribute to both. “When we started playing together, it was like meeting a special woman and falling in love,” Andy Cole once said of his famous partnership with Dwight Yorke at Manchester United, and perhaps there is something similar going here between Sane and De Bruyne.

Credit, too, is due to Pep Guardiola, for creating the right drills, the right exercises, the right environment for the relationship to flourish to this level of complexity in such a short space of time. Atherton said that in all his years of batting, there were only three players with whom he developed this near-telepathic understanding: Alec Stewart, Graham Gooch and Neil Fairbrother, all of whom he batted with for more than five years. De Bruyne and Sane have been playing together for 14 months.

But there’s a third theory, and this is more about De Bruyne than it is about Guardiola or Sane. What if De Bruyne is simply a next-dimension, off-the-wall, freak-of-neurological-science, bona fide genius? What if, on some impenetrable level, De Bruyne can see Sane making the run before he has made it, perhaps even before Sane himself has decided to make it? We’ll call this theory the Dr Manhattan theory, after the superhero character in the Watchmen comics who as a result of a tragic nuclear accident no longer perceives time in a strict linear sense but sees past, present and future all at once, swirling concurrently through his conscience like a giant shape-shifting plasma.

Genius on the football pitch often appears to the mortal eye like clairvoyance. Watch any YouTube compilation of Lionel Messi assists, or perhaps someone like Andres Iniesta or Luka Modric at their very best, and you will occasionally see them play passes that only they could see. Connoisseurs of the spectacular assist may prefer the sumptuous diagonal cross De Bruyne played to Sane for City’s sixth goal in this same game, whipped in at an improbably perfect trajectory through a forest of legs.

It was an incredible assist, but it’s as much about execution as concept. It’s a frighteningly difficult ball to play. But at least De Bruyne can see the picture with his own eyes before he plays it. If we accept the premise of the Dr Manhattan theory, by contrast, this pass from De Bruyne to Sane is on a level beyond even that. It’s a pass not even De Bruyne could see, but one that as a result of his innate footballing intelligence, his perception of space and time and probability, he played anyway.

So, which is it? Fortuitous accident, incredible telepathy or otherworldly genius? Perhaps it’s a combination of all three. Perhaps there’s another explanation entirely. I’m willing to bet every penny in my pocket that not even De Bruyne himself knows for sure. But for now I’ll be watching his every move, reading the runes, searching for clues, trying to gauge the size and shape of his greatness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments