How profits replaced passion at the heart of Nike

It was far more subtlety, far less swoosh in the early days, says Ian Herbert, but now the firm that was inspired by Steve Prefontaine’s memory has become the world's biggest sports brand with the help of some dubious associations

There was an emotional core to Nike once, in the days before their determination to be the richest, most ubiquitous brand led them to suffer the dubious coincidence of being the one attached to Lance Armstrong, Tiger Woods and Oscar Pistorius when each of those individuals plumbed the depths of notoriety.

Athletics was a source of joy as well as income to the company back then and the community they created to help develop track and field stars was called Athletics West – a more homespun name and place than the pseudo-science fiction Nike Oregon Project which has mired British Athletics, its poster boy Mo Farah and its very well-paid consultant Alberto Salazar in controversy and suspicion this past week.

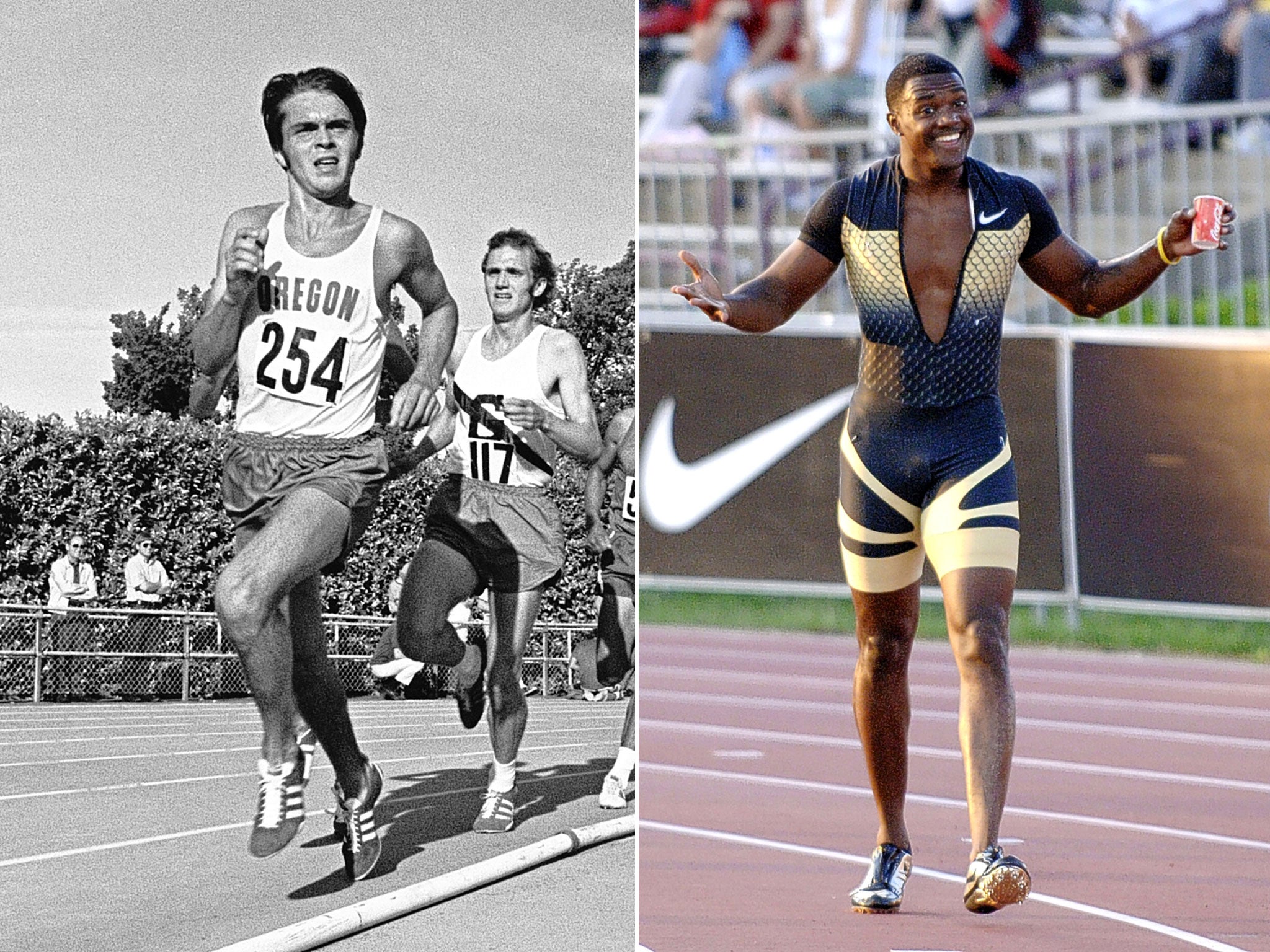

It was there, in Eugene, Oregon, that the sports footwear firm stumbled on a short, handsome, tough local carpenter’s son called Steve Prefontaine, who set the world of distance running on fire in their shoes and made it to the cover of Sports Illustrated in June 1970. They called him just “Pre” and when he was killed in 1975, after his little gold MG skidded into a rock wall and he was catapulted onto the pavement by the impact, they grieved. It took the firm that would become Nike years to get over the loss.

It was far more subtlety, far less swoosh in those days. For years after changing the name to Nike Inc in 1980, they kept the firm’s original “Blue Ribbon Sports” name on the letterhead and the marketing strategy was “whispering loudly”: nothing too obvious. But now they bestride sport, bankrolling vast parts of it and satisfied – from that imperious position – to have just taken two-times drugs cheat Justin Gatlin back onto their payroll, while athletes such as Britain’s Jo Pavey, Greg Rutherford and Steph Twell and the American 1500m London Olympics silver medallist Leo Manzano have been dumped.

Neither does Nike seem to have harboured much agitation about Panorama’s investigation into Salazar. The company has not returned my calls on him, or Gatlin, this week. They’re yet to publish a word on either topic.

The cultural shift came not long after Prefontaine’s death as Nike realised that buying up and developing the world’s new athletes was the way to catch up and overtake Europe’s Adidas, an aim they had accomplished by 1980. They tried to retain the underdog spirit for as long as they could, but there was a desperation and frustration about how to generate an output of winners from Athletics West. Spending money there stopped them breaking the sport’s amateur sanctity but the problem was the Russian and East German athletes who were enhancing their performances through steroids.

Julie Strasser, a former senior Nike executive who was the company’s first advertising manager and wife of the late Rob Strasser, one of the firm’s three founding fathers, tells me that Athletics West began examining steroids as a way of helping athletes’ recovery from workouts in the late 1970s. “Is it justifiable to do that when the other guy is cheating?” she asks, rhetorically. “I don’t believe steroids are cheating. It’s so important to get muscle, you know. People still have to train and put the work in, even if they take them.”

In her 1991 book Swoosh: the Unauthorised Story of Nike and the Men who Played There, Strasser chronicles how Nike strategy meeting minutes revealed Athletics West’s fascination with steroids as a training aid. She quotes insurance records detailing testosterone tests and liver function tests, undertaken by athletes there, to test the physiological effects of steroids. The coach who ran Athletics West at the time has denied steroid use.

Strasser also reveals how little sentiment there has ever been, where Nike and its choice of athletes is concerned. That is why they have always sponsored individuals – never events. “They like the brash, stylish, talented individuals who get them attention,” Strasser says. “They are not going to drop any individual bad boy unless it is a catastrophe – a murder – he’s committed. They would reason that they’ve never been damaged by any athlete. I remember we laughed when [the] Converse [apparel] brand once sponsored the referees. How stupid is that? Nobody likes referees.”

So here is the fabric of the story of a marketing strategy which would leave those companies seeking a pure image running for cover. Nike’s creative use of bad boys goes all the way back to the 1981 John McEnroe advert – “McEnroe’s favourite four-letter word” – and though Strasser insists that the company has “never had its reputation damaged by any athlete”, many who stand for sanctity and positivity have been burned in the past few years alone, because their faces have not fit.

The Independent has spoken to a number of British athletes who have proved a less attractive proposition to the firm than Gatlin, who was brought back onto the roster despite testing positive for amphetamines and testosterone. It’s been a familiar routine for them: a regular review meeting is scheduled, an athlete who has experienced success heads into it expecting to renew and is then told the relationship is over. For some it is the end of the valuable three-monthly “kit drops”. It’s worst for those whose training regimes in South Africa and competition in the United States are contingent on Nike’s cash.

For a few – such as Rutherford, dropped by Nike despite delivering long jump gold which was one of the finest moments of London’s 2012 Olympics and presenting a modern, attractive face of athletics, who is highly engaged on social media – it has simply meant taking himself to partners who appreciate him. The same goes for Pavey, now sponsored by Adidas. Her several other sponsors – Silentnight, Intel and Thule – prevent any dependency on one.

Nike has not been the big bad wolf in every sense. Good relationships have existed. The former Nike manager Dave Scott, who for a long time drove the decision on which British athletes were engaged and dropped, was popular with many. But several athletes attest to it being a different type of relationship with Adidas.

“It wasn’t all about the money with them,” says one. “They were excited to have you on board. They said, ‘You are a great role model’. That dimension interested them.”

Manzano is just puzzled. He won America’s first 1500m Olympic medal in 44 years at London and his is a compelling story as a Mexican immigrant made good. “Maybe it’s my age,” the 30-year-old told Sports Illustrated.

It would be easy – and wrong – to characterise Nike as a one-dimensionally ruthless machine. They are the most active sponsor of US track and field athletes, even though most are paid a £10,000 annual subsistence income and yet more just get the kit drop. And – make no mistake – it has become a dependency culture between UK Athletics (UKA) and Nike, too. The only reason why it took until yesterday afternoon at 2pm for UKA to provide a detailed media briefing on the Salazar allegations is that organisation’s need to discuss it first with Nike. UKA needs the £15million Nike deal – double the previous Adidas figure – which UKA chief executive Niels de Vos negotiated with them two years ago. Three years on from London 2012, Nike has British athletics over a barrel.

That is where the risk of exploitation comes in. Nike wants material evidence that its partnership is worthwhile. It was the same with Armstrong and it took the company a full six days after the publication of a damning 1,000-page dossier exposing the cyclist as a serial drug cheat, in 2012, before the company severed links with him. A coach needs to deliver them the tangible evidence for the investment to keep coming.

“When that happens, then a corporate with deep pockets has every incentive to play the same game that a coach might have,” Ross Tucker, a specialist in endurance running and professor of exercise physiology at Free State University in Cape Town, says. “They not only fund all the coaching behaviour, good and bad, they also drive it. They’re active participants rather than passive bystanders. And here, the game might involve fancy gadgets like underwater treadmills and altitude houses [that] scream ‘innovation, technology, advanced thinking’. These are the attributes the sponsor loves to communicate.

“But if this innovation is ineffective, and can’t deliver visible results, then why stop there? And that’s the slippery slope that leads so many people to view the Oregon Project with suspicion. If you’re pulling out all the stops to make your athletes faster, then why stop at the line of legal? Why not push a little further into the grey and then into the black, as is now alleged…?” Salazar and Farah categorically deny any wrongdoing.

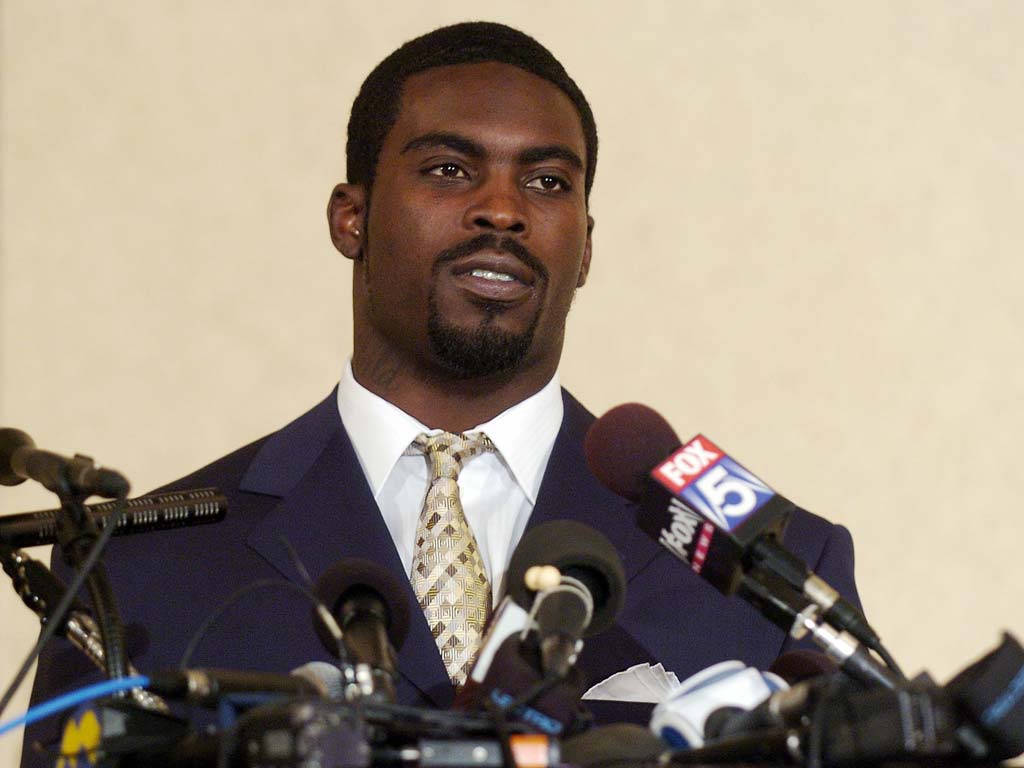

Another case there was no opportunity to discuss with Nike this week was that of their American football star Michael Vick, jailed in 2007 after admitting appalling cruelty to 70 dogs – mainly pitbull terriers – he was using in an illegal dog-fighting ring. The court case heard that dogs that performed badly were hanged, drowned and electrocuted and that Vick and his associates would throw family pet dogs into the ring, so they could watch the pitbulls rip them apart. Nike rewarded him with a new four-year sponsorship deal when he returned to the sport on his release from prison.

It isn’t the Nike Steve Prefontaine most probably knew. “Of course it’s changed,” says Julie Strasser. “It used to be run by individuals. Making a profit wasn’t the primary reason to get up in the morning. But then it became a corporation. It used to be that you could give a guy a pair of shoes and he would talk great about Nike. It’s not like that any more.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments