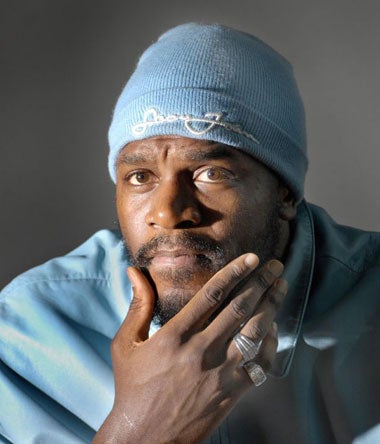

Audley Harrison: 'Before it was anger driving me. Now it's strictly business'

Brian Viner Interviews: He used to be all talk, but a couple of devastating defeats (not to mention a spell doing chi gong on a Florida beach) have focused the former Olympic champion's mind

About a year ago, on Vero Beach in Florida shortly after sunrise, a group of elderly people practised chi gong, an ancient Chinese exercise related to tai chi, scarcely aware that they were being closely watched by a huge man out for an early-morning run. Had they seen him and known something of his distant past, which included jail sentences in England for robbery and assault, they might have needed to take deeper, more meditative breaths than normal. The man drifted away, but the next morning he was back, this time asking if he could join in.

He was cheerfully admitted to the group, and in due course began meeting some of them in the evenings for dinner - an even more incongruous spectacle than the beach exercises, for he was yards taller, years younger, and a different colour. They told him their life stories. The man learnt that one of his new friends had recently lost his wife to cancer, that another's husband had drowned, and that the chi gong sessions, led by a likeable Jamaican called John, gave them spiritual nourishment as well as physical satisfaction.

By now they knew that the man's name was Audley Harrison, that he was a British boxer, and that a devastating blow had been administered to his professional reputation following a humiliating defeat in December 2005 at the hands of his compatriot Danny Williams.

Whatever promise Harrison had shown by winning Commonwealth and Olympic gold medals as as an amateur in 1998 and 2000 had wilted in the years since. The lucrative contract he signed with the BBC after turning pro was widely considered to be one of the biggest blemishes on the otherwise impressive CV of Greg Dyke, then the BBC's director-general. Harrison's company, A-Force, was ridiculed, as was his determination to make his own fights. The most powerful man in British boxing, the promoter Frank Warren, habitually called him "Fraudley".

What a difference a year makes. With his former nemesis Warren now in his corner, Harrison goes into the ring against his old sparring partner Michael Sprott tomorrow with more credibility than he has had in years. He cites the chi gong sessions, the inspiration he got from the way his Floridian friends had handled their various tragedies, marriage to a Las Vegas hairdresser called Raychel, the birth last year of their daughter, Ariella, and indeed reconciliation with his own mother after decades of estrangement ("we're not lovey-dovey but we've made a connection, and she's met the baby"), as factors in his comprehensive defeat of Williams two months ago, when he did what many pundits thought beyond him, fighting with skill and purpose to achieve a third-round knockout.

As a result, the prospect of Audley Harrison, heavyweight champion of the world, is no longer a laughing matter. Matt Skelton awaits him if he beats Sprott, with the winner of that fight likely to get a crack at the WBO title held by the American Shannon Briggs.

And so to a room in the Wembley Plaza Hotel, overlooking the badlands of north-west London where Harrison grew up brawling and stealing. I have interviewed him once before, and was seduced then by his extraordinary charisma and eloquence. This time I am warier, because his deeds since we last met haven't remotely lived up to the beguiling chat he gave me, and yet I leave an hour later captivated once more. If he could box like he can talk he would already have emulated his heroes Lennox Lewis, Muhammad Ali and Jack Johnson.

"Jack Johnson's biography is the quickest book I've ever read," he tells me. "He was a maverick, so ahead of his time, a great technical boxer, but what he did out of the ring, taking on the system... a lot of my own nonconformist attitude came from people like him and Muhammad Ali. I'm controversial too, but I need to match my feats out of the ring with my feats in the ring. Hence the alliance with Warren. He will help me to win the world title, and defend it three or four times."

To reach those rarefied heights he must first meet the relatively prosaic challenge of taking Sprott's European Union crown around the corner at Wembley Arena. I ask him what he expects of his opponent? "He's cagey, with good defence and good hand speed. He's not a massive puncher, he has average power, but he believes he can win. But where I'm going, he's in my way, basically. He can't win. Any time I lose from here on in is because the guy outclasses me. That's not going to happen on Saturday."

Most boxing experts agree. So after all the sneering - much of it, in truth, justified - he must enjoy being talked and written about as a genuine contender, I venture. He smiles. "It's the paradox of sport. You see it with the England cricket team. A terrible Ashes, totally ridiculed, then they come back and win a one-day tournament, now everyone's saying they have a chance to win the World Cup.

"People judged me on the first Williams fight, but now I've given them something else to to gauge me by. If you see what [Vitali] Klitschko did to Williams, it took him eight rounds. I destroyed him. But it's true that before the first fight I said, 'Right, this is it, the L-plates are off, the learning curve is over.' And I wasn't able to take advantage. Then I lost [equally humiliatingly] to [Dominick] Guin.

"My manhood was challenged. Spiritually and emotionally I was pretty low. I went to Vero Beach on my own to train. I knew I wanted to carry on boxing. I didn't want to be a 50-year-old man, bitter, hating the system. The only way was to let go of the anger, to realign my faith in God, and to change my motivation."

His motivation? "Yeah. As an amateur I had an Olympic dream, and when I turned professional it was with the same ideals. I was still doing it for the glory, and because of the deal with the Beeb I didn't have to worry financially. But the reality is that this is my profession, this is how I get paid, and if I lose my next fight, where's the next pay cheque coming from?

"I'd never thought like that before. Before it was the anger driving me, getting back at the system, childhood things. Now I don't need that. It's strictly business now. I have a family to provide for, and I've been smart with certain investments, but I'm not yet in a position where I can retire and live on the beach."

If anyone can guide him to contented retirement, maybe even running a chi gong class, it is Warren, whose endorsement of the man he once called "Fraudley" is a volte-face comparable with Sam Allardyce and Arsène Wenger going on holiday together. Harrison, an Arsenal fan, acknowledges the analogy.

"I don't think it was ever personal on Frank's side, although a lot of slanderous things were said about me and not just by him. There were plenty of others who got on the bandwagon. I admit it got personal on my side, but eventually I realised that a lot of people in the public eye get crucified in the same way. Beckham, reality stars, royalty, I'm no more special than them. I also realised that the person who was the root of most of my problems was Frank, and that I might as well go to the root of the problem.

"My business manager Hazel was in my ear all the time, saying that I should go back and fight in the UK. She had a meeting with Frank, and now we have a relationship which makes sense on both sides. It makes sense to bring a big hitter to our team and now I'm two fights away from a world title. I'm like the horse coming through at the back. I'll win a world title, and walk away from boxing on my own terms."

He concedes, however, that this is not exactly a golden era for heavyweight boxing. "Having four different champions is not ideal, but actually it's ideal for the fighters, because having one champion in this day and age, with so many fighters, means you could be waiting half your career to get a shot. But next year I believe the heavyweight division will be unified, and everyone will say boxing is great again, because when heavyweight boxing is in good shape, boxing is in good shape.

"I think 2008 will be rosy for boxing and rosy for me. Boxing needs someone with charisma, and I have that on both sides of the Atlantic. The Americans are prepared to adopt me just to take a belt off one of the Russians." With that irresistible thought Harrison's eyes wander to the window, and I invite him to focus on the urban sprawl beyond, and to consider where he has got to, compared with where he might have been.

"Yeah, there are some sad stories out there. Sad stories. I'm still in contact with most of my old friends, and a lot of them are still in the same tough neighbourhoods we grew up in, trying to be law-abiding. But it's tough. Life's tough."

It was half a lifetime ago that he was sent to Feltham Young Offenders' Institution. He is 35 now; he was 17 then. "I got 32 months, which was a harsh sentence. There was a gang of us, up to a lot of mainly petty stuff. I'd been to three different schools, I was like a dog with no home, running wild. I sat in prison until I was 19, thinking, 'I've got no qualifications. It's strategy time now. I have to go to college.'

"Then I came out and turned into Mr Righteous. There was this guy smoking on the bus behind me, and everyone was complaining. I said, 'Can you put out the smoke?' but he didn't, so I pulled the cigarette out of his mouth. He stood up, and I gave him, you know, a little tap. He claimed I stabbed him, which was total baloney, but I admitted assault and I went back for two or three weeks. That wasn't fun. I said, 'Right, that's it. This bad boy phase is over.'

"I went to college, and about the same time I started boxing. I'd had a fight with a guy in the street, a friend of mine actually, but something happened and I had to kind of defend the family honour. You ask about my old friends. Well, the guy I had the fight with is gone now. Murdered. But afterwards someone asked if I was a boxer. I said I'd never boxed in my life. They said, 'You were throwing proper boxing punches.' That made me go to the gym and give it a try.

"I used to smoke weed. I gave that up. I got fit. I went to [Brunel] university. I was determined to succeed but in England that attitude isn't always celebrated. In England they dent your aspirations, stunt your positivity. That's why I like being in America. In America I can be myself."

He, Raychel and Ariella live in Vegas, the capital of brash artifice, but also the home of hitting the jackpot. Either way, it is plainly the right place for him.

Tale of the Tape: The lowdown on Audley Harrison

Division: Heavyweight.

Nickname: "A-Force"

Born: 26 October 1971, London.

Height: 6' 5".

Weight: 251lb.

Reach: 83cm.

Education: BSc (Hons) Sports Studies and Leisure Management.

Turned professional: 19 May 2001.

Pro record: 21 wins (16 KOs), 2 losses.

Amateur record: 46 wins, 8 losses.

Belts: WBF World Heavyweight Championship (2004, three fights).

Titles: Olympic Games Heavyweight Gold 2000, Commonwealth Games Gold 1998. Made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in 2000.

They say: "I've sparred with Harrison and I knocked him about. Basically he's fat, can't fight and can't knock anyone out. He's not strong enough to smash an egg with a baseball bat"

Herbie Hide, 2003

He says: "In 2007 I will win the world title, in 2008 I will be undisputed. I have definitely got the skills"

After beating Danny Williams, December 2006

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies