James Lawton: Soviet conflict

Sinister, ruthless... and successful. The Communist system for sport provoked hatred and awe, but cracks were appearing long before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Our writer, who witnessed the good and the bad, looks back at a lost empire

In its own forlorn way it is a relic now of an unimaginable time, almost as much as the Berlin Wall whose fall signalled its collapse. But then if you happened to be in the upstate New York town of Lake Placid in 1980 you would never forget both the awe and the hatred provoked by the Soviet Union sports system.

The "Miracle on Ice", when a young team of amateur and college boy ice hockey players brought down such fabled Soviet stars as Viacheslav Fetisov and Sergei Fedorov, is still so vivid in the American sports memory, it is as though it happened not 29 years ago but barely a month.

Townsfolk rushed into the frozen streets to be nearer the big, gaunt ice rink which had just been identified as the venue for a triumph unprecedented in nearly 30 years of sport-based ideological warfare.

The TV commentator who called the action, Al Michaels, entered folklore, along with the team led by Mike Eruzione, son of a Massachusetts blue-collar worker, when he defined the extent of the victory in the final moments... "Eleven seconds, you've got 10 seconds, the countdown going on right now..." he cried. "Morrow up to Silk... five seconds left in the game. Do you believe in miracles? YES."

A miracle perhaps it wasn't but it was an astounding victory. It was a crack in the monolith of Soviet sport which, however contaminated by institutionalised drug abuse and viciously imposed state control, had for decades produced an army of superb sportsmen and women. For the Americans, who had so long reviled the sporting expression and propaganda of something that would be described by their forthcoming president Ronald Reagan as the "evil empire", a kind of vindication had come on that winter night in the Adirondacks.

It would take another nine years for the complete victory of one system of sport over another. This came when some of the remnants of the beaten Soviet team eagerly joined up with National Hockey League clubs, Sergei Pryakhin leading the exodus when he joined the Calgary Flames. In North America, the former foot soldiers of sport exchanged their Red Army uniforms and government-bestowed flats, malfunctioning Ladas and status as heroes of the Soviet Union for lifestyles that they could never have imagined when the Berlin Wall separated one world from another.

In ruins, along with so many other Soviet certainties, was the idea that sport was the perfect demonstration of the superiority of the Communist dream. The health and the brilliance of its young sportsmen and women would sing in marching anthems of a society which had installed values which would mock the decadence of the West.

A much harsher, more corrupt version of reality would emerge soon enough, but for some years the image of Soviet sport did carry an astonishing glow.

When a young, apolitical Bobby Charlton arrived in Moscow with the England football team in 1958 – a time when Soviet strength was being registered with dramatic power in almost every branch of sport – he was dazzled by the facilities he found. He was also sharply disappointed when he was told he had lost his place in the team to Bobby Robson, which meant that he would not be performing in the vast Lenin stadium. "I got the news," recalled Charlton, "after training on one of the many pitches at the Lenin Sports Palace complex. I had been much taken and inspired by the scale of the Lenin complex.

"The huge stands of the stadium, which catered for more than 100,000 spectators, seemed to reach up to the sky and the surrounding facilities included cycle tracks and swimming pools. I didn't know much about politics but I was quite moved to think that all this had been built for young sportsmen and women. I could not avoid making comparisons with home, where such a complex was unknown.

"We had the Crystal Palace in England but this in Moscow was on an entirely different level. I hated the fact that I would not be able to play in such a setting."

He would no doubt have been less impressed had he visited the last Soviet football team to compete in the World Cup finals in Mexico in 1986. They were staying in an extremely basic motel on the outskirts of the town of Irapuato, from where they had produced some fine performances in group games, most notably in a 6-0 defeat of Hungary and a superb1-1 draw with the France of Michel Platini. It seemed like some kind of miracle when you compared the living conditions of the Soviets and the French. Platini's men were staying in a luxurious hotel in a colonial mountain-top town. The Soviets sat glumly in their motel, listening to the grinding gears of trucks labouring up the hill that stretched into the mountains, a string of red team shirts drying in the sun burning into a small courtyard.

Yet if the sportsmen and women of the West were separated by a vast gulf in lifestyles, for so long there was no reflection of this in the rankings of success, and especially in the Olympics.

The appearance of the first Soviet Olympic team brought stunning triumphs in Helsinki in 1952, when 71 medals, including 22 golds, left them second only to the United States, who had surrendered first place only once in the seven previous summer Games, and then to the Third Reich under the flinty gaze of Hitler.

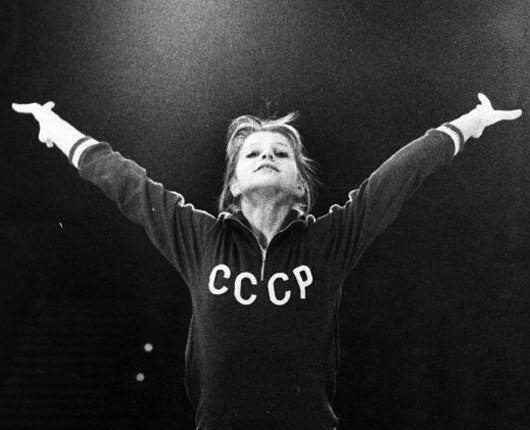

Most striking were the Soviet women gymnasts, who were proclaiming a brilliance that would last, through tears and pain and even the freezing of their menstrual cycles, until the break-up of the empire. The success of Soviet women athletes was a particular provocation to the Americans, whose media wrote of "strong Red ladies", who were not only the product of a "sinister system" but also threatening to cross the gender divide by one means or another.

Yet if the Soviets had their leading athletes specialise almost from their toddling days, and if drug experiments in sport were adopted as a state industry by their formidable satellite East Germany, it was still true that the system offered some glorious examples of both brilliant and passionate performance.

Supremely, Helsinki was the stage for the superb Czechoslovakian distance runner Emil Zatopek. However, in terms of commitment and versatility there were few rivals for Aleksandra Chudina, who achieved a unique treble when she collected silver medals in the long jump and javelin and a bronze in the high jump.

One truth was evident as the Soviets went on to win six of the next eight Olympics, denied by the Americans only at Tokyo in 1964 and Mexico City in 1968, when they were required to draw most comfort from the embarrassment of their conquerors when Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medallists in the 200 metres, made black-power salutes from the winners' podium.

What was clear from the tide of success was that the Soviet sports system was ruthless – and unforgiving of all those who failed to meet its exacting standards. It had, despite the frugality of the rewards when compared with those available in the West, created an extraordinary urge to win at all costs.

However, if you wanted to see the pressure that was inflicted – and some of the most desperate of its consequences – much of it could be seen in the haunted faces of two members of the Soviet team in Montreal in 1976 – Boris Onishchenko and Olga Korbut.

Onishchenko was an honoured Olympian, a colonel in the Red Army when he arrived in Montreal already holding silver and gold medals from the modern pentathlon at Mexico City and Munich. He left in disgrace after being caught cheating by the British captain Jim Fox. Onishchenko modified his épée so that it registered non-existent hits. He fled to Minsk, where he worked as a taxi driver.

Korbut's descent from her world-wide fame as the little angel of Munich, a sprite of a gymnast who bewitched TV audiences from San Diego to Sydney, was not so rapid but it was still an agony, and you saw the first hint of this on a balcony at the athletes' village. Tear-stained, she had retreated there with the weight of her understanding that her glory had been usurped by the Romanian teenager Nadia Comaneci.

"It is so hard," she said, "when people expect so much of you. It all seemed so easy in Munich. Everything was fresh then, now I feel I have disappointed so many people." She was 21 years old, a has-been who in Montreal could win only win a mere team gold medal – against the three she had gathered in Munich, two of them individual. Now, two divorces and a conviction for shoplifting later, she lives in Arizona, a sad legacy of the mightiest empire sport would ever know.

Yet some heroes and heroines of the people survived their ordeal in a way that never diminished the idea that they had been born to be part of an effort, however doomed in reality, to portray the best of an empire's potential.

At the peak of his career, sprinter Valeri Borzov held off the advance of an all conquering generation of American fast men, winning double gold in Munich and double bronze in Montreal. Then, he married the goddess of Soviet sport, the exquisite gymnast Ludmilla Tourischeva, who was born in the now war-scarred Russian province of Chechnya. The marriage of the "supremely serene" gold medallist to the blond flier from the Ukraine was a symbol of the strength of Soviet athletic resources, a motherlode of human potential.

Tourischeva brought shivers to the spine, so brilliant and calm was her work and no one who was at Wembley to see her triumph in a World Cup event in 1975 will ever forget the supernatural poise she displayed on an uneven bars apparatus that was clearly on the point of collapse. However, she completed her exercise a moment before the bars crashed to the floor and did not take as much as a backward glance. Her trainer Vladislav Rastorotsky declared, "Ludmilla would fight to the death in any situation."

Certainly it was one mark of the Soviet sports empire. Also, there was a drive to push back the limits of performance that was personified by the serial world-record breaker Sergei Bubka in the pole vault.

He started his pursuit of glory as an 11-year-old in the Dynamo Youth Sports School in Ukraine and finally won Olympic gold in Seoul in 1988, the climax to an extraordinary record of breaking the six-metre mark that had been considered a barrier equivalent to the one that used to be represented by the four-minute mile, on no less than 45 occasions.

At that time in South Korea so soon before the break-up of the empire, he was found in a Russian liner moored in the harbour of Incheon. The elite of the Soviet team were pampered on that part of the ship which would normally have been reserved for high party officials. Bubka carried the aura of a master of Soviet sport – and declared, "I love the pole vault because it is a professor's sport. One must not only run and jump but also think. It is a challenge that has dominated my life but I do not regret it. I love it because results are immediate and the strongest is the winner. Everyone knows it. In everyday life that is difficult to prove."

When he broke the world record at an astonishing 6.14m (20ft 13/4in), a mark that still holds, he remained restless for higher goals, declaring, "My jump was imperfect, my run-in was too short and my arms were too far back. When I manage to iron out these faults I know I will improve."

There are many epitaphs for the lost empire of sport and Bubka's would probably not rate too highly among the residents of Lake Placid, NY. However, like so many of those who came from the Steppes and the Urals and the wheatfields of Ukraine, he was a kind of miracle too.

The Wall game: How the landscape changed after the Cold War

Losers... East German football clubs

There is not one former East German club in the Bundesliga, the united country's top flight. Dynamo Berlin, who won 10 successive titles pre-reunification with the support of the Stasi, have been beset by financial problems and now play in Germany's fourth tier. Without state backing, clubs such as the Dynamos, Berlin and the habitual runners-up Dresden – who boasted Matthias Sammer among others – could not match their western rivals. Energie Cottbus of the second division are now the highest ranked of the eastern clubs.

Winners... East German footballers

Sammer had won 23 caps for East Germany when the wall came down and that paved the way for a move west to Borussia Dortmund and a stellar career that peaked when he was a driving force in Germany's 1996 European Championship triumph and was named European Footballer of the Year. Reunification allowed the East German players freedom of movement and, for the best of them, access to the riches available to their western counterparts, none more so than Chelsea's Michael Ballack, who was born in Görlitz on the Polish border.

Winner... Ukraine

A core provider of athletes to the Soviet system, Ukraine has emerged as the strongest of the former socialist republics outside Russia. They won seven gold medals at the Beijing Olympics – the same as France – and their total of 27 in disciplines as varied as wrestling, shooting, judo, archery, canoeing and athletics, left them a very creditable 11th in the medal table. Belarus have also made their own name, taking four golds in Beijing, where their winners were given government rewards of $100,000 – and a life-time supply of sausages.

Loser... Russian gymnastics

The Soviet Union dominated Olympic gymnastics, winning 73 golds and 184 medals in all, with Larissa Latynina claiming 18 on her own in the 50s and 60s. But now left on their own, Russia have not claimed an Olympic gold in the discipline since 2000. The break-up of the Soviet Union led to a drastic fall in state subsidy for many sports and gymnastics was particularly badly hit. Many of the specialist schools and training centres were shut down and the reduction in athletes was accompanied by an exodus of their top coaches to the West.

Loser... Ice hockey

Russian players made up the majority of the Soviet teams that monopolised Olympic and world competition. Of the nine Games they contested, the Soviets won seven of them, winning silver in 1980 and bronze in 1960. In the four Olympics that they have competed in as Russia they have finished fourth, second, third and fourth. In 2006 in Turin they were hammered 4-0 by Finland in the semi-finals. Russian players remain among the best in the world – the top three nominations for Most Valuable Player in the US NHL this year were all Russian, with Alexander Ovechkin, the winner, regarded by some as the best in the world – but as a unit they cannot hold a torch to the Soviets' might.

Winner... China

Once again an authoritarian Communist power sits on top of the Olympic medal table, but not comfortably so in western eyes. Suspicions of drug use have hung over the remarkable rise of the country's swimmers, while under-age allegations have swirled around their gymnasts. China's rise has coincided with the demise of the Soviet Union. In the Seoul Games of 1988, the last in which the Soviets took part, China won five gold medals, 50 fewer than the Soviets, and finished 11th in the table. In 1996 they were fourth, in 2000 third, in 2004 second and in Beijing last year first.

Robin Scott-Elliot

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks