Sumo under siege

As a stable master awaits trial for the death of a young apprentice he allegedly ordered to be beaten, David McNeill talks exclusively to the sport's first European champion about the scandals that plague it

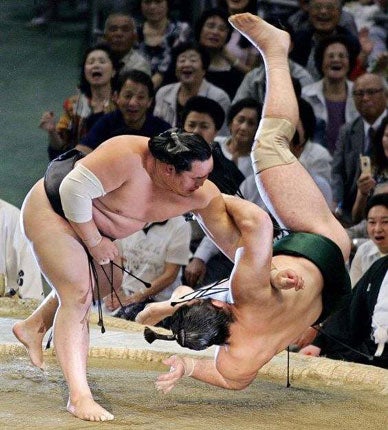

A weak sun barely warms the Tokyo dawn, but one tiny corner of the city is already sweaty and humid, filled with the dull thumping sound of giant naked men slamming into each other. Buttocks red and stained brown from the mud floor, the men are a grunting, force of nature – all the more intense for carrying out their combat in almost total verbal silence.

Little prepares the uninitiated observer for a morning sumo workout, which is filled with painful insults to the flesh. Heads attached to bodies weighing up to 160kg clash at bone-crunching speed, apprentices are tossed around like bags of rice; wrestlers practise by ramming their shoulders against a solid wooden post as thick as a small tree.

As we watch this session in the Sado Gatake stable, 30 minutes west of Tokyo, a skinny apprentice in outsized mawashi (loincloth) is repeatedly slapped and flung to the floor by larger men. When he starts to weep, snot and tears dripping from his face, they slap him harder. "You have to be able to endure and ignore pain," explains Kotooshuu, one of the sport's top stars, after the workout. "If you can't, you shouldn't be here."

That philosophy, amped up to lethal levels, fuelled the killing of Takashi Saito, a 17-year-old apprentice who died in June 2007 after a session at one of Japan's most prestigious stables. A latecomer to the sport, where apprentices usually start at 15, Saito's "vague attitude" to his future career irritated stable-master, Junichi Yamamoto, who allegedly ordered him to be toughened up. The lesson was applied with a metal baseball bat and beer bottle, an assault that stopped Saito's heart and reportedly left his jaw hanging from its sockets. Yamamoto, who denies instructing wrestlers to beat Saito, is on bail awaiting a manslaughter trial.

Saito's death has added to the sense of a sport under siege, following a string of lurid stories about match fixing, drug taking and hazing. Even before these allegations were aired, the number of new apprentices had fallen by a third since the 1990s, according to its ruling body, the Japan Sumo Association (JSA), as youngsters shun the dohyo (sumo ring) for football, baseball and computer games. Sumo's yokozuna (grand champion) Asashoryu spoke for many when he lamented that young Japanese now exercise their thumbs and little else, says Doreen Simmons, a veteran British-born sumo commentator for the state broadcaster NHK.

"Sumo has always been a place where a boy who wasn't especially good at anything else and who might have been a big layabout could get on and be successful," she says. "It teaches them basic things like manners, cleanliness and being respectful. But it's a hard life and there are softer options." Like many sumo supporters, she views Saito's death as "tough love" that went badly wrong. "The good news is that there are 53 other sumo stables in Japan where nobody has been killed."

Sado Gatake denies that Saito's hazing and Yamamoto's upcoming trial have had any impact on recruitment. But the JSA, which took months to investigate Saito's death before expelling Yamamoto, admits that parents now ask increasingly tough questions when dropping their sons off at these sometimes remote stables. It now dispatches teams of observers to regularly check on sumo discipline.

Apprentices live a spartan existence, training, sleeping and eating twice daily a fattening broth in a sort of monastic collective that has few parallels in professional sport. Until the association recently outlawed it, discipline was enforced with a yard-long bamboo stick. Stable masters oversee strict hierarchies, only slightly exaggerated in the widely believed rumour that apprentices wipe the bottoms of the older wrestlers. "That used to go on, but it has been stopped," says Kotooshu, real name Kaloyan Stefanov Mahlyanov, who is the sport's top-ranked Western wrestler, and one of Sado Gatake's biggest earners. "But what you have to understand is that being in that position, at the lowest rung of sumo, is what spurs you on to succeed."

As local recruitment wanes, sumo has turned to foreigners like Kotooshu to fill out its ranks. A 6ft, 8in Bulgarian with pin-up good looks and manners to match, he has helped conservative Japanese accept the idea that this most traditional of sports no longer belongs exclusively to them. Last year he made history by becoming the first European to win sumo's top prize, the Emperor's Cup, adding to its foreign domination: Mongolians Asashoryu and Hakuho fill out the top ranks.

But the foreign influx, held within limits by a JSA quota that allows only one non-Japanese per stable, has been plagued with controversy. Asashoryu has repeatedly broken sumo rules and was suspended for misconduct in 2007. Russians Wakanoho and brothers Roho and Hakurozan became the first active wrestlers to be kicked out of the sport last year following allegations of pot use.

Shockingly to many Japanese, Wakanoho responded by washing the sport's dirty mawashi in public with tabloid allegations of match-fixing implicating its top stars, including Kotooshu, who he says offered him one million yen (£7,000) to take a dive to the dohyo.

"You have scruples, but you will get used to this," Kotooshu was reported as saying in the tabloid magazine Shukan Gendai. "The sumo world may look good from the outside, but inside it's different. So don't worry."

Today the Bulgarian calls the allegations, which were subsequently retracted, "bullshit". "Magazines pay people to say those things. There is no match-fixing in sumo." His claims have been strengthened this month by a libel defeat for the same magazine, following earlier match-fixing claims. The JSA, which denies all allegations that wrestlers throw bouts, was awarded 15 million yen by a Tokyo judge, who called the allegations "unproven".

The ruling is unlikely to end the smears against the sport, but at least it gives it some breathing space, says Simmons. "Like any sport where money and fame are involved, there has been a constant struggle in sumo between good and evil, so talk of a constant slide down is ridiculous," she says. "But it has to get its house in order, and it is doing so."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies