The Big Question: Why is Britain so good at cycling, and is there a lesson for other sports?

Why are we asking this now?

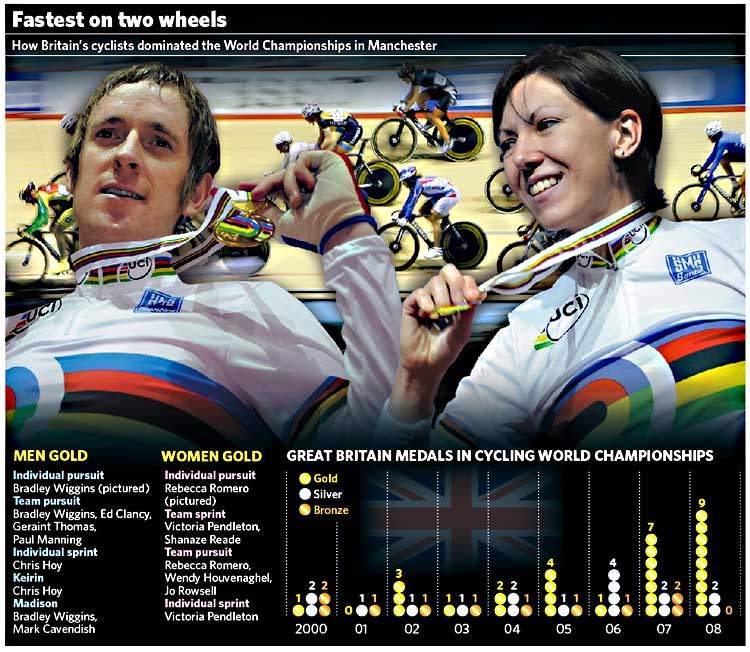

The British team dominated the world track championships, which ended in Manchester on Sunday, winning more gold medals than ever before. The home team took gold in nine of the 18 events and topped the medals table by a wide margin.

So who are our stars?

Bradley Wiggins won three gold medals, in the individual pursuit, team pursuit (in partnership with Paul Manning, Geraint Thomas and Ed Clancy) and madison. (Pursuiting is essentially time-trialling, with the riders racing against the clock as much as their opponents; the madison, which Wiggins won in partnership with Mark Cavendish, requires endurance and sprinting skills as well as tactical awareness.)

Victoria Pendleton, a short-distance sprinter with a scorching turn of speed, won gold in the individual and team sprint events and a silver in the keirin, which tests sprinting speed and racing skills. Chris Hoy took gold and silver in the men's individual and team sprints respectively and gold in the keirin. Rebecca Romero won the women's individual pursuit and teamed up with Wendy Houvenaghel and Jo Rowsell to win the team pursuit.

Have these people come from nowhere?

Not at all. Britain has enjoyed increasing success ever since winning three track cycling medals, including a gold, at the Sydney Olympics eight years ago. The 2004 Games in Athens were even more productive. British riders have dominated recent world championships and World Cups. They won seven golds at the 2007 world championships, a tally few thought could be beaten in Manchester this year.

What's the secret of their success?

The Government would like to claim some of the credit. Andy Burnham, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, was in Manchester and was quick to point out the importance of National Lottery funding. Britain's elite competitors are indeed funded to the tune of more than £5m a year, which enables 22 riders to train full-time at the Manchester Velodrome. And Lottery funding increases according to success.

But there is much more to it than cash. Peter Keen, who was the national performance director at the Sydney Olympics, and Dave Brailsford, in charge since 2003, have been inspirational leaders and have recruited some of the world's best coaches and sports scientists. Two of Brailsford's most recent signings typify the quality of their team: Jan van Eijden, a German former world sprint champion, and Scott Gardner, an Australian recognised as the world's leading sprint sports scientist, are both working closely with Pendleton.

Brailsford believes in seeking an advantage in every conceivable field, including nutrition, fitness, medicine, coaching, tactics, psychology and technology. Chris Boardman, who won Olympic gold 16 years ago on a revolutionary bike, heads a research and development team that is constantly looking for ways to make British bikes go faster. Brailsford deliberately held back some technical innovations in Manchester so that his riders can spring a surprise in Beijing.

But didn't a British rider fail a drugs test in Manchester?

Rob Hayles was not allowed to ride after a pre-race "health check" showed that his blood haematocrit level marginally exceeded the maximum allowed. The test measures the capacity of the blood to carry oxygen. High haematocrit levels can be an indication of illegal blood-boosting, but they are not regarded as proof.

Brailsford, who is an outspoken critic of drug-taking and insists on rigorous in-house testing of his riders, believes Hayles is innocent. He thinks the blood haematocrit test may be outdated and suspects that British riders record high levels as a result of the team's innovative nutritional and training practices. His riders consume large amounts of substances like cod liver oil and cherry juices and their haematocrit levels tend to rise when, unlike most of their rivals, they cut down sharply on their physical training just before a major event.

Where does this leave our Olympic hopes?

There are 12 track cycling events at the Olympics and Britain has the world champions in seven of them. But success is not a foregone conclusion. The pressures at the Games are greater, other riders may have been aiming to peak at Beijing rather than Manchester (the British also see the Olympics as the bigger goal though they were keen to excel in front of their own supporters) and Brailsford's squad will not have home advantage. But it would be a major surprise if they did not return with a helmet full of medals.

If we're so good at cycling, why can't a British rider winthe Tour de France?

Road racing is very different to track cycling, although some riders, like Wiggins and Cavendish, combine the two. The British track squad work as a national centrally-funded unit, whereas road racing teams are generally backed by big multinational sponsors. Road racing is a major sport in countries like France, Spain and Italy, but it has minority interest in Britain and only a handful of British riders compete internationally on the roads.

Is cycling the Olympic sport we're best at?

Cycling, rowing and sailing have been the most productive Olympic sports for Britain in recent times. On current form the cyclists are likely to bring the most medals home this summer.

What can other sports learn from cycling?

The Frenchman Arnaud Tournant, one of the world's great cyclists, said at the weekend that: "Great Britain is probably the only professional track team. The rest are amateur." A similar difference might be identified between track cycling and other British sports, which have been slower to appreciate the difference that the best medical and scientific advice can make.

The quality of coaching in other British sports has also been questionable, though, like cycling, more and more are looking abroad. Athletics and swimming have traditionally provided Olympic success for Britain, but they have declined in recent times. British track cycling may also benefit from having fewer major international competitors than sports like athletics and swimming, in which major investment in equipment is not required.

Concentrating resources has been beneficial for British track cycling. Whereas all the best British riders are based in Manchester, swimmers and athletes train at different locations around the country.

Is Britain poised for Olympic cycling glory?

Yes

*Results at the world track championships proved that Britain has the world's best cyclists

*No other country can match the professionalism of the British team and its technical support

*The establishment of a national academy has ensured that the flow of British talent will continue

No

*The pressures at the Olympics are huge, and the British squad may falter under the weight of national expectation

*Other countries may well have been holding more in reserve in readiness for the Olympics

*Britain took advantage of being on home territory in Manchester. The Chinese are likely to do the same in Beijing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments