Golden touch of new British messiah wins over crowd

A vintage game, its rhapsodic shifts of rhythm played out in the gloaming of an immaculate summer evening. But the cathedral of British tennis can sometimes seem a theatre of the absurd as well. The wait for a Briton who can win this tournament has become very like the wait for Godot, an attempt to give futility a purpose of its own. Is Andrew Murray the messiah? After this tumultuous match, at least it seems possible.

His electrifying defeat of Richard Gasquet had the immediate look of a turning point. To salvage a first quarter-final appearance after the Frenchman had served for the match in the third set represented an indelible statement. If the crowd did not believe in Murray before, they will now. And vice versa.

So much of the ritual is already familiar, thanks to the Sisyphean Wimbledon career of Tim Henman. Murray, it was said, had yet to achieve the same intimacy with Centre Court, perhaps because he has still to perfect that abiding sense of doom.

Until now, in fact, the one thing holding him back among the burghers of Middle England had been the simple fact that he is not Henman. How do they compare the two? Well, they can easily picture Henman on skis; Murray, in contrast, looks suspiciously like a snowboarder. You can picture the arch looks in the queue for the lift as he careers into their midst, with insolent dexterity.

So his relationship with them is not a glib one, and that is no bad thing – for either party. It may help preserve him from the trappings (and that is assuredly the word) of the inane idolatry that infects the modern values of this country. And it will preserve those who yearn for something a little more unctuous from delusions about the past. They had their brats in the good old days, after all; it is just that their surliness tended to have an extrovert hue. Meanwhile Roger Federer wanders around looking like Gatsby.

After a performance like this, public respect for Murray will assuredly become true affection – and, as such, it will count for something. There is nothing counterfeit about the boy, with his laconic, sometimes peevish mien. In the first set he had used up all his challenges by the fifth game. As the match seemed to unravel, moreover, he took out his vexation on an authority figure – a line judge – and was promptly reprimanded by the umpire. "Code violation." Perfect. The code of the Woosters, perhaps? There have been harder lessons learnt in Dunblane.

In fact his bearings seem to have a very true compass in his mother, who has clearly given him far more than a tennis pedigree. She remains his rock and, lest we forget, is also the foundation of another accomplished, spirited talent in Andrew's brother, Jamie.

Murray seems to have found stability, too, in his relationship with Kim Sears. No doubt it comforts the nation to see Murray's decorative companion, covering her eyes in dismay or flushing with joy. Television producers, after all, helped to carve Henman's image by constant reference to his courtside support, his restrained and elegant family up from the shires.

Now they are doing the same for Murray. To have these touchstones – these vestal assistants to the man in sacerdotal white, playing out a precious midsummer rite – builds faith among those inclined to superficial mistrust or censure.

Murray has discarded the baseball hat, which was instead worn by the French villain. They said that this match would turn on "which head Gasquet had on" when he entered this crucible, and he obliged by wearing his hat back to front. And that was pretty much how he played this game. At first he was full of dastardly Gallic feints, flourishing his backhand like a cutlass. Murray, meanwhile, betraying a reckless, chronic addiction to the drop shot, was constantly at full stretch to stay in the match.

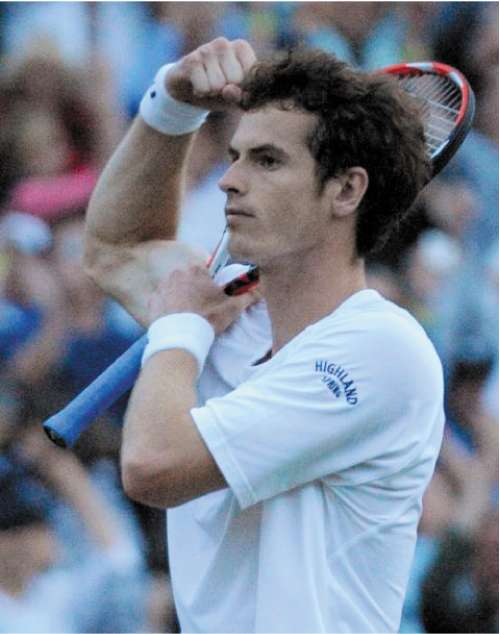

At full stretch, however, he can do some pretty extraordinary things, repeatedly breaching the laws of physics. Perhaps the defining moment came when he clinched the third set tie-break by salvaging a ball from the front row, and then stood among them like a demagogue, pumping his fists. Suddenly Godot was on the front step.

Gasquet is himself only 22, and palpably disintegrated in the patriotic uproar. Towards the end he made a melancholy plea to the umpire, ostensibly over the fading light, more probably over the contagious energies of the crowd.

For a while he promised to reduce Murray to heroic failure. The Scot's game was strewn with unforced errors. A quixotic failing, and of course a very British one. Much more of this, you thought, and they really will take him to their hearts.

But then he showed his empire-building side. And as the dazed crowd wandered into the evening, you could almost hear Vladimir and Estragon among them, wondering what to do if Godot did not come today? "We'll come back tomorrow." "And then the day after tomorrow."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies