Open Eye: A lay view of history

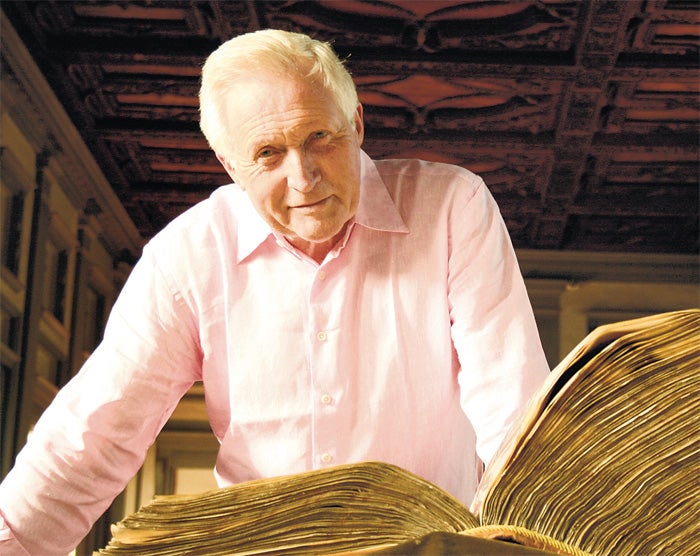

'Seven Ages of Britain' began on BBC1 on Sunday. Yvonne Cook talks to presenter, David Dimbleby

The novelty of Seven Ages of Britain is that it tells the story of each historical period through the objects it produced. What different insights do you get from this approach?

The objects are chosen because they bring the past alive, and talking about them, enthusing about them, handling them, looking at them, is a vivid way to bring the past alive. It's not an illustrated history - the objects make it. Normally on television, you start by writing the history and then you illustrate it as best you can, with computer-generated images, or sometimes by just standing in front of a camera and talking. With this series, you take the objects and you enjoy them, you enthuse over them as a presenter, and you use them to explain what it tells you about life at the time.

Has it changed your view of history?

It has, I suppose, in a way. I'm not a historian by training: I read philosophy and politics at university, so my view of history is not a historian's view. What it does is to plunge me back into the past and make me feel almost that I belong to the period I'm talking about, that I'm immersed in it. It is a very layman's view of history - deliberately so, really.

The first programme has the Sutton Hoo treasure, and the last one has Damien Hirst and the Austin 7. Would you say history has gone from the sublime to the ridiculous?

No, I wouldn't at all. The things that are left from the early period are the sublime, because they are the most precious. But the Austin 7 is to me an object of great beauty, and is also seminal because it marks the opening of opportunity to the working class to travel independently, to have a proper motor car at the same price as a motorbike and sidecar. So it's important and it tells you something about the culture and the civilisation. There are other objects that have the same effect: Henry VIII's armour, for instance, or the Cheapside hoard, a huge box full of jewels worth several million pounds, now in the Museum of London, found by a builder in Cheapside in the last century.

Are all the objects well known?

Funnily enough, they aren't. Even King Charles' shirt, that he wore at his execution, is hidden away in a box in the Museum of London.

Was it a privilege to be able to handle these objects?

It was a huge privilege. And enjoyable, too. But the privilege of being able to open and handle and touch books, say - sometimes with gloves - is a first part of the energy and enthusiasm you can put into talking about things. If you see them as they are seen in a museum, behind glass, they remain dark, they are not alive for me in the same way.

You've done two previous BBC1 series with historical themes: A Picture of Britain (with The Open University) and How we built Britain. Is there any connection?

I suppose that they do form, in a way, a kind of informal trilogy of programmes, one about the discovery of landscape and its effect on the British psyche, one about power structures and how we came to build the buildings we did, and now one about the influence of art and what it tells us about the past. But they weren't designed like this - one followed another depending on the success of the previous one.

I've always been quite interested in social history and political history. I made, way back - actually the best work I ever did, I think - a series called The White Tribe of Africa, about the history of the Afrikaner people and how apartheid came about. And then I made another series called An Ocean Apart, which was a history of the relations between Britain and America from the First World War to the present day. But then years passed before they asked me to do another.

It all seems a long way from Question Time, which is the series you're probably best known for. Which do you prefer?

I wish I knew, because then I could decide which to do. They play to different pleasures. I love the adrenalin rush of Question Time, and the excitement of politics, and we've had an amazing year with various things - Nick Griffin and the expenses scandal, and this and that. That's very exciting and it gets you out of bed in the morning. On the other hand, these other ones are hugely enjoyable to do, there's a kind of serious pleasure in being able to see all these objects or go to the buildings or see the paintings. But it's completely exhausting doing both together - they're both very hard taskmasters.

Anything else we should know about Seven of Ages of Britain?

I think I should say that, while it's all about making things popular and accessible, it's also got the rigour of The Open University behind it, and of other curators and historians. We're very grateful for that, because it allows me the freedom to say what I want to say, knowing that they'll check that it's within the bounds of accuracy and not just invented off the top of my head.

Open Eye is the monthly bulletin of The Open University community

Editor: Yvonne Cook

E-mail: open-eye@open.ac.uk

Address: Open Eye,

Communications,

The Open University

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

For OU courses information, call 0845 300 6090; or see open.ac.uk/courses. The Open University (OU) is the UK’s only university dedicated to distance learning. More than 2 million people have studied a course with The Open University.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies