Patrick Leigh Fermor profile: 'Glitteringly told, impossibly romantic, unrepeatable today...'

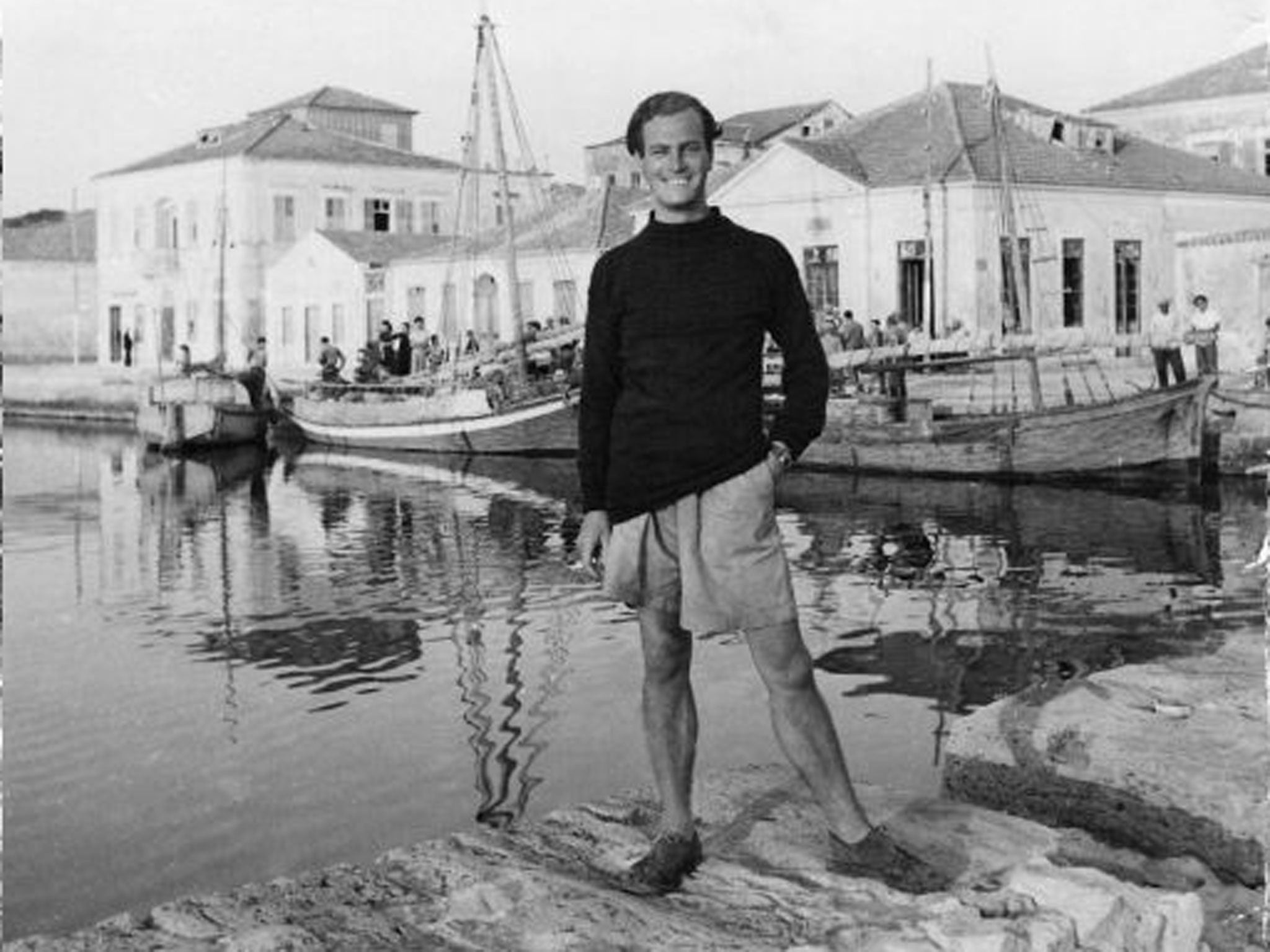

As the long-awaited final volume of Patrick Leigh Fermor's memoirs is published, Jonathan Lorie celebrates the brilliant travel writer

"This is the Byron Room," murmured John Murray the seventh, ushering me into the Regency drawing room of his publishing house in Piccadilly, where marble busts perched on carved bookcases under a white rococo ceiling. "And that fireplace is where they burned Lord Byron's papers after he died." He smiled sheepishly, for it was his own ancestor, John Murray the second, who committed one of the great vandalisms of literary history – burning the poet's scandalous memoirs instead of publishing them. "And here," he said with some relief, "is Paddy."

Paddy, as Patrick Leigh Fermor was always known to friends, was a great crag of a man, scowling at a wooden desk, where a page of lopsided writing in black ink was refusing to do his bidding. "It's no good," he raised his tousled head and glowered at us, a handsome man with dark, mischievous eyes. Then he burst out laughing. "It's a poem in medieval French I want to send to the Spanish ambassador, but I can't remember the end of it!"

Leigh Fermor strode briskly over, despite his 89 years, shook my hand and launched into an unstoppable reminiscence of tramping across Europe in 1933. "I borrowed £15 from somebody and caught a boat to the Hook of Holland, heading for Constantinople. I got somebody to give me a letter to a very nice baron in Bavaria and I went to stay with him … And then I borrowed a horse off somebody and crossed the whole of the great Hungarian plain on this horse – it was the right way to see it – it was totally unspoilt then ... At the Iron Gates I caught a ship for about 50 miles, then stayed with a very nice consul in Sofia …" And he rattled off the names of places and people that must have vanished long before I was born, in a lost world of feudal Europe, as though it were all just yesterday.

That epic journey and the power of his storytelling will be in many people's thoughts this weekend, as Leigh Fermor's final book of travel memoirs is published. Fans have been waiting three decades for this. The Broken Road is the last, missing volume in a trilogy that many thought would never be completed. It concludes the story he told that day in the Byron Room, of a youthful trek from London to Istanbul in 1933, catching the last echoes of an older order before the Second World War changed everything.

Across this vanished world Leigh Fermor had walked aged 19, meeting monocled aristocrats and ragged chimney sweeps, sleeping in cowsheds or in castles, dodging gypsy encampments, cadging lifts on cargo boats, falling for pretty girls, dancing and drinking and talking his way to the heart and soul of central Europe. The journey was enchanting, the writing rich and vivid.

But he never finished the trilogy. The two previous volumes – A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water – appeared in 1978 and 1986 to huge acclaim. They prompted Jan Morris to hail him as "the greatest of living travel writers". Then the words stopped, 500 miles from Istanbul. For years, friends and fans pestered him to finish it. He never did. Perhaps it was the failing powers of old age, perhaps it was the pressure of living up to expectations, perhaps – like that medieval French poem – he could no longer recall enough of the ending. When he died in 2011 – seven years after our meeting in Piccadilly – it seemed another great loss to literature.

But three years before his death, his biographer Artemis Cooper had stumbled across a 45-year-old typescript filed at John Murray's office. It was called "A Youthful Journey", and it was Leigh Fermor's early attempt to describe the post-Danube part of the route. Her interest rekindled his, and slowly he began to sift his way through this fading text, revisiting the great journey, reworking the words, a man in his nineties taking one last shot.

He never finished. The final manuscript was a mass of revisions and expansions that petered out just days from Istanbul. But Cooper and the travel writer Colin Thubron took it upon themselves to sort it into best order and present it to the world. It was perhaps a homage to their friend as much as a literary laying to rest. And John Murray published it, a posthumous memoir saved from oblivion at last.

The result is The Broken Road. It's as charming as its predecessors, a fascinating glimpse of a vanished era. Leigh Fermor drifts through the pre-war Balkans, meeting White Russian officers, dancing at diplomats' parties, falling in love with a French-speaking student, drinking slivovitz with coachmen and concierges. On a moonless night by the Black Sea he nearly drowns, but stumbles his way into a cave where a ragged gang of fishermen and sailors sitting around a fire take him in for a night of wild drinking and traditional dances. It is perhaps the emotional heart of this book – a moment from an ancient myth, which his derring-do and joie de vivre have brought to life – glitteringly told, impossibly romantic, unrepeatable today.

The book is also a little rougher in parts than its predecessors. I asked the editors about this. "What we were dealing with was very much a first draft, by his standards," says Colin Thubron. "Neither we nor anyone else could finish the trilogy as Paddy would have wanted. It is, inevitably, less uniformly polished – or 'buffed up' , as Paddy might have said – than the previous two books. But there are passages as fine as anything he wrote, and it also reveals a certain, rather charming, youthful vulnerability."

"It is much rougher in texture," agrees Cooper, "but it is also unmistakeably Paddy. As a writer he is quite unique. That fusion of memory and imagination and landscape, nobody has ever achieved that with such immediacy."

Quite how far he fused memory and imagination is an interesting question. All three of these books were written decades after the fact, with only a tattered map as aide-memoire. He had lost all but one of his diaries – some on the road, some in a neglected storeroom at Harrods. Like that other fine travel memoirist of the 1970s, Laurie Lee, you can't help wondering how much of this actually happened.

Cooper has a theory: "Paddy once told me that everything that ever happened to him from the ages of five to 21 was etched on his mind, and to a certain extent that was true. But memory is not a CCTV camera in your head – it changes, develops, shrinks or expands or becomes more elaborate – especially if you write about it."

Thubron agrees: "I think the vividness of his memory merged seamlessly with the richness of his imagination."

It was an imagination fed by the life that he chose to live. What other travel writer can claim to have ridden in a cavalry charge across a castle drawbridge with sabres drawn, as he did during a Balkan rebellion? Or lived in a manor house with a Romanian princess, who he met on reaching Istanbul? Or kidnapped an enemy general and driven his staff car through 22 enemy checkpoints, as he did in wartime Crete?

The latter was his most famous exploit, and you can visit the place where it happened – a remote stretch of road beside an olive grove where Leigh Fermor lay in wait with a band of Cretan partisans. The episode was made into a book and film, Ill Met By Moonlight, starring Dirk Bogarde as Leigh Fermor. For years afterwards, Leigh Fermor was fêted throughout Greece for his wartime service with the partisans, when he had lived for months in mountain caves, organising resistance to the German occupation.

The war left him with a profound attachment to Greece and its people, and in the 1950s he and his wife Joan built a house there, on the Mani peninsula. It was famed for its elegance and its house guests. John Betjeman described the library, which looked over the sea, as "one of the rooms of the world". The travel writer Bruce Chatwin chose to have his ashes scattered on the hills above, by Leigh Fermor.

Here he wrote two luminous books on Greece – Mani and Roumeli – and slowly began the trilogy which has now, finally, been completed. He nicknamed this work "The Great Trudge" – a view understood by his editors.

"It feels wonderful to have completed the trilogy," says Cooper. "Paddy always felt a huge regret that he did not finish this book. But by the end of his life I think he knew that we would see it was published. Perhaps, on some level, he was able to leave the world knowing that it would see the light of day."

"There is, in the end, nobody like him," concludes Thubron. "A famous raconteur and polymath. Generous, life-loving and good-hearted to a fault. Enormously good company, but touched by well-camouflaged insecurities. I would rank him very highly. 'The finest travel writer of his generation' is a fair assessment."

A life in print

The Broken Road is published by John Murray, £25 hardback. Murray also publishes the other books in the trilogy, A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, along with Mani and Roumeli.

Artemis Cooper's biography, Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, is an excellent and entertaining account of his busy life.

The Cretan Runner is a first-hand memoir of the wartime resistance by partisan George Psychoundakis, who fought with Leigh Fermor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks