Aah, Mr Bond... we've been expositioning you!

Some fictional characters can withstand endless reinvention, as the new 007 book shows. When it comes to creating durable brands, art beats commerce every time

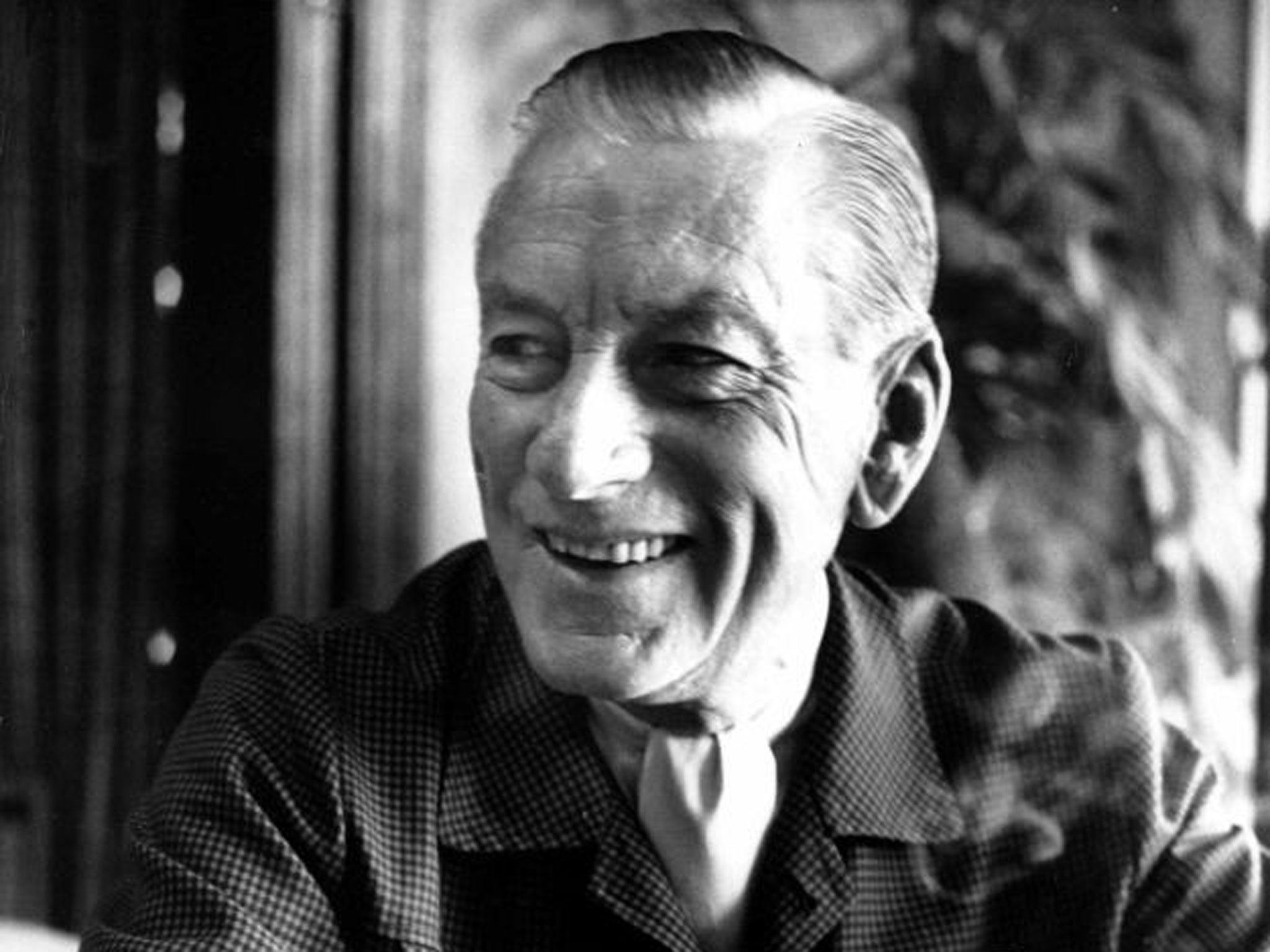

The first batch of critics bidden to inspect Solo, William Boyd's newly published contribution to the James Bond franchise, returned from their stake-out with the discovery that Boyd has, as one pundit put it, gone back to basics. As my colleague, The Independent's Nick Clark noted the other day, Boyd's Bond is not the spectacularly muscled hunk of Skyfall, last year's $1bn-grossing 007 movie, but the one thought by his original creator, Ian Fleming, to resemble the 1940s singer-songwriter Hoagy Carmichael: "a tall, lean, rangy, very dark-haired, good-looking man".

Boyd himself, speaking at Wednesday's press conference at the Dorchester, suggested that the link between Fleming's Bond and the man last seen trying to outfox a cyber-terrorist who had brought MI6 to its knees, "gets fainter and fainter" each year. In this context, Solo is a rather revolutionary work: most fictional heroes whose sponsors yearn to keep them alive through periodic reinventions of this sort have a fatal habit of turning into what a literary theorist would call a "floating signifier" – someone whose appeal is, on the one hand, universal, and, on the other, tantalisingly vague, who has moved so far from his (or her) original incarnation that he can take on any guise that his re-animators contrive for him and yet still emerge with the public on his side.

Take, for example, the extraordinary series of transformations visited upon Sherlock Holmes, first sent sleuthing his way into the late-Victorian consciousness all of a century and a quarter ago on the publication of A Study in Scarlet (1887). Even now, over eight decades since the death of his begetter, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, any impressionist who sashays on to a screen clad in an Inverness cape and a deerstalker hat and murmuring the words "Elementary, my dear Watson", can be fairly confident that four-fifths of those watching will have at least a vague idea of who he is taking off.

And immediately one of the chief difficulties faced by the fictional character whose popularity is such that he or she goes sailing off into a mass-cultural world where the usual laws of representation don't apply and the diktats of the "brand" take over looms ominously into place. For just as Queen Victoria is thought by 19th-century historians never to have spoken the words "We are not amused", so Holmes, according to the textual bloodhounds, never actually uttered his signature remark. Neither did he ever sport that trademarked piece of headgear, which was apparently brought to the party by the actor Basil Rathbone in his widescreen portrayals of Holmes sometime in the 1930s.

If this kind of reinvention had an almost protean effect on the band of actors subsequently commissioned to interpret Holmes for the film and television audience, then the mark left on the even larger collection of writers desperate to move Holmes forward into the 21st century is yet more flagrant still.

Not long ago, to mark the arrival of Anthony Horowitz's Baker Street caper, The House of Silk, a US newspaper asked me to write a piece about Holmes' "posthumous adventures", in pursuit of which an enthusiastic intern assembled every sample of the great detective's post-Conan Doyle adventures he could find on Amazon. These came in three large crates and must have amounted to more than 100 books – a series of increasingly outlandish tales in which a collaborating Holmes solved escapologist crimes with the help of Harry Houdini, refined the psychological profiles of some of his adversaries alongside Sigmund Freud, confronted giant rats of Sumatra and tried his hand at unmasking Jack the Ripper.

There were even – curious to relate – novels in which he wandered off into territory previously occupied by other writers – messed about in H P Lovecraft-land, say – and had his "hidden years" zealously unpicked. As with certain of James Bond's recent re-imaginings, a purist might wonder how any of the writers involved got away with their plunder. The answer would probably be that this, whether one likes it or not, is what happens to art when it gets diffused to an endless series of marketplaces and constituencies for whom the original conception of that art needs some kind of update; the general effect is like throwing a bottle of black ink into a goldfish pond.

The purist would probably retort that this kind of serial re-invention is a characteristic of popular art – you can't re-imagine Madame Bovary – and yet to set against him is the fact that the same process can be seen at work not only among the characters created by "serious" writers but among the writers themselves.

Over the past 100 years or so, for example, Charles Dickens has been reinvented as "almost a Catholic" (by G K Chesterton) and as a proto-Marxist. The forthcoming BBC series about his relationship with Ellen Ternan will apparently present him as an actress-seducer and the father of an illegitimate child, despite the fact that no conclusive evidence of either relationship or paternity exists.

In much the same way George Orwell is nearly always brought before the public these days as a kind of secular saint – a process which involves ignoring several aspects of Orwell's character – and by way of drawings of him that portray a kind of walking cadaver with a toothbrush moustache and a cigarette taped to its lower lip. There are, as it happens, photographs in the Orwell Archive at University College London that suggest a plumper and much more bonhomous figure, but somehow they rarely make it on to the pages of newspapers.

But Orwell, you see – and I admit to having taken part in this exercise myself – is now a brand, whose interests are protected by executors and agents bent on bringing the most appropriate version of him to a public whose lower end is in grave danger of thinking that "Big Brother" began life not in Oceania but as a reality telelvision show.

To go back to William Boyd's new James Bond adventure, the significant point about the modern 007 is that he, like Holmes and even like Dickens and Orwell, can do absolutely anything, take on any task, assume any persona. He is the modern equivalent of the Expanding Man of the Marvel Comics. Rather than complaining about this elasticity we should be celebrating the fact that all these careers – both real and imaginary – are ultimately a demonstration of art's superiority to commerce, something that, it could be argued, needs demonstrating as regularly as possible.

You might even decide, copy of Solo duly plucked from the Waterstones shelf, that Ian Fleming pulled off a trick that no industrial marketing team or widget manufacturer has come anywhere near to perfecting: he created the everlasting brand.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks