Beware of the jovial buffoon who picks fights overseas

Never mistake Boris for Falstaff. He is Prince Hal.

More than any pantomime, the two halves of Henry IV sired a whole tribe of comic archetypes. Home-grown drama has shamelessly aped them ever since the pair of history plays gave William Shakespeare a double smash in the late 1590s. At present, London has no meatier holiday treat than director Gregory Doran’s robust, picturesque and tastily old-fashioned staging of both parts with the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Barbican.

If much of the audience comes for Antony Sher’s rumbustious but self-seeking Sir John Falstaff – “that trunk of humours, that bolting-hutch of beastliness, that swollen parcel of dropsies, that huge bombard of sack, that stuffed cloak-bag of guts” – then they will leave having met the originals of other favourites too. As Mistress Quickly, the veteran landlady at the Boar’s Head in Eastcheap, Paola Dionisotti sometimes put me in mind not so much of Barbara Windsor’s Peggy Mitchell in EastEnders as June Brown’s imperishable Dot Cotton. But that’s to get cause and effect “topsy-turvy down” (a phrase from Henry IV, Part I).

The Boar’s Head regulars stand, or sway, at the root of a family tree that, in its modern branches, takes in music-hall turns, Ealing comedies, Carry On… films and more sitcoms and soaps than you can shake a jester’s staff at. Some critics have found Sher comparatively charmless. Exactly: behind all the bar-room bonhomie, and the crowd-pleasing cynicism (“Can honour set to a leg? No: or an arm? No: or take away the grief of a wound? No”), Falstaff thieves and plots and manoeuvres on his own account, always willing to sacrifice his low-born hangers-on. As for the clear-eyed panorama of a disunited nation plagued by “rank diseases”, where all authority looks like a trick or sham, the Henry IV plays never lose their topical bite. I arrived at the Barbican thinking about how well the wise-cracking, bibulous Falstaffian style has served Nigel Farage this year. (Remember that the fat knight and his crew commit a brazen mugging at Gadshill outside Rochester.) I left thinking the analogy just a trifle obvious. At the heart of the plays lies not the thirsty bag of guts but Prince Hal, the long-game schemer who masquerades as a jovial buffoon. As Hal – played by Alex Hassell as the ultimate, oafishly cocksure Hooray Henry – confides during his Machiavellian soliloquy early in Part 1: “I’ll so offend, to make offence a skill,/ Redeeming time when men think least I will.”

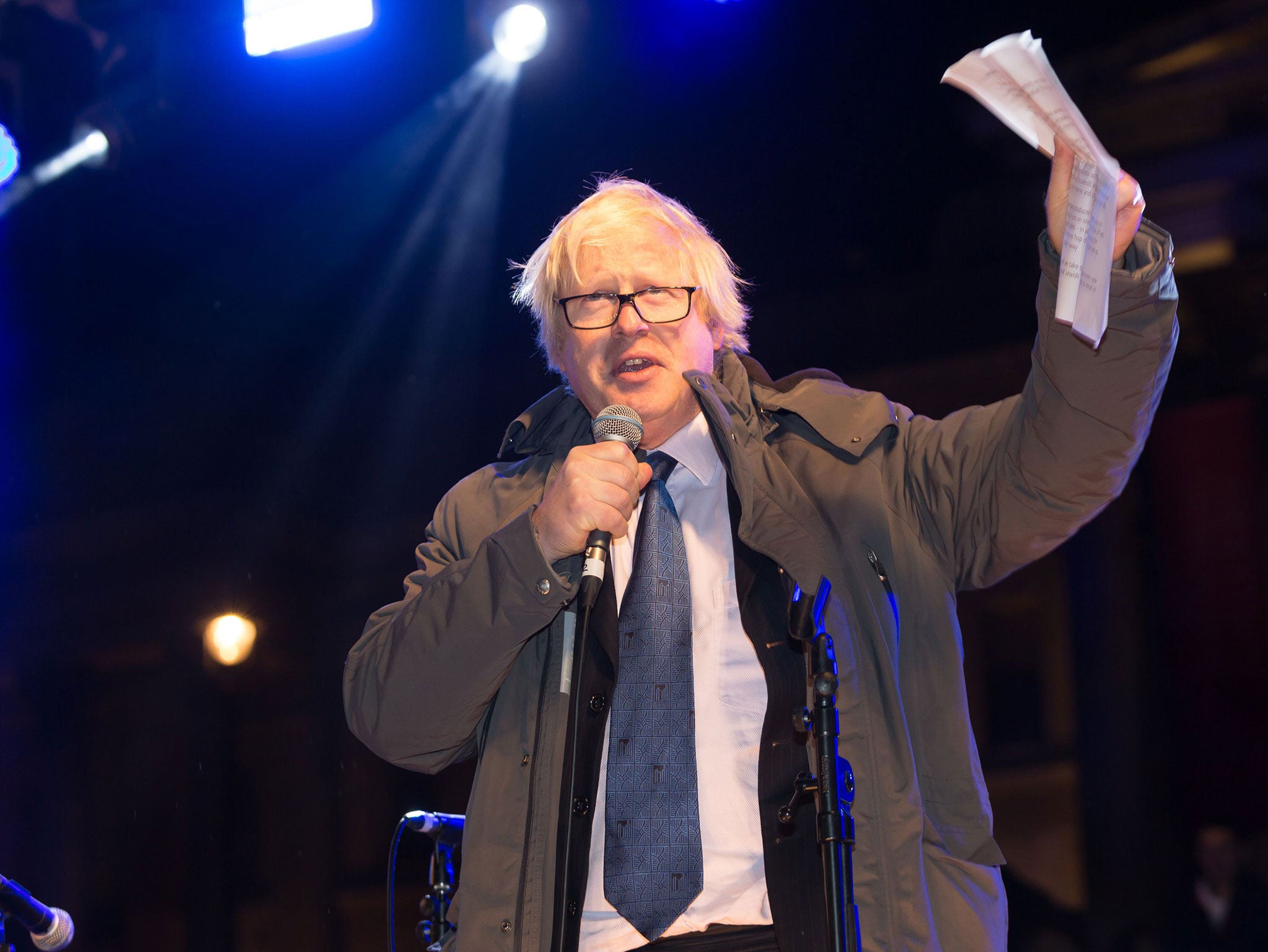

The Ukip leader’s Falstaffian progress gave 2014 its keynote performance. Next year, the plaudits may well belong to another “politician” (for Shakespeare, the word is always a deadly insult). As things stand in our own fissile kingdom, it is hard to look forward to December 2015 and not see the shadow of the current Mayor of London falling over grand affairs of state. Whatever algorithms of electoral fate direct his role in opposition or in government, Boris Johnson stands to gain. In the New Year, his makeover as a compassionate and open-pursed “One Nation Tory” – with the “living wage”, big-ticket infrastructure projects and English devolution as feathers in his cap – will gather pace.

The prospective Conservative MP for Uxbridge and South Ruislip has cannily sidestepped the pool of bad blood seeping between Theresa May’s Home Office and Downing Street. King David and Chancellor George now count on his loyalty as a prime asset. But after Friday 8 May, in whatever Elizabethan cesspit of impassable confusion the polls leave behind, all bets may be off, from Eastcheap to Edinburgh.

Never mistake Boris for Falstaff. He is Prince Hal. Over the coming months, watch the merry mask of hedonism slip. “So, when this loose behaviour I throw off,” Hal promises, he will impress “By how much better than my word I am”. The prince’s new-found uprightness “Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes/ Than that which hath no foil to set it off.” Prepare for the wave of surprised acclamation that greets the dedicated Mayor-turned MP and his “reformation”: no longer a scatter-brained madcap, but a sober-sided, socially responsible national master-planner. Like the homage to Churchill paid by his Christmas best-seller, it all forms part of the storyline.

No scenes in Shakespeare have a greater power to chill the air than Hal’s twin repudiations on Falstaff. In Part 1, he acts in the role of his austere father Henry IV in a tavern charade. To the tipsy knight’s entreaty (“Banish plump Jack and banish all the world”), he glacially replies: “I do. I will.” At his coronation in Part 2, the new-minted Henry V cuts down his portly boozing chum for good: “I know thee not, old man: fall to thy prayers;/ How ill white hairs become a fool and jester!” I suspect that we may hear the Johnsonian equivalents to “I know thee not, old man” fired off in various directions before long.

Thanks in some measure to the Shakespearean tradition, a flair for comedy gets you a long way in British public life. It certainly did no harm to Churchill. Conversely, its lack can strike us as a disability. Twelve months ago, in his end-of-year diary for the London Review of Books, Alan Bennett mused on Margaret’s Thatcher’s passing. The playwright scolded her as a “mirthless bully”. He maintained that “to have no sense of humour is to be a seriously flawed human being”; such a blind spot “shuts you off from humanity”. Yet she reigned for more than a decade. Dry, taciturn, modest Clement Attlee trounced Churchill himself in 1945. The Mayor of London knows his history. Our new Hal may soon retire the burlesque persona for good and call time on the zip-wired hellraiser: “Presume not that I am the thing I was;/ For God doth know, so shall the world perceive,/ That I have turn’d away my former self”.

Shakespeare’s state-of-the-nation epic stays evergreen in almost all political weathers. After the coronation, with the flames of rebellion hardly cool, the new king’s brother asserts: “I will lay odds that, ere this year expire,/ We bear our civil swords and native fire/ As far as France”. So would I. On what ground would a minority Tory administration choose to fight its Agincourt? Again, expect to find the Euro-averse former Mayor in the front rank.

Labour as yet has no answer to the swaggering confidence of Harry “Hotspur” Percy of Northumberland – and, in the absence of Alan Milburn, no Geordie pretender to the part either. From the opposite coast, Andy Burnham could well pick up the standard if the bloodbath of 7 May leaves one or more parties leaderless. Over the border, Alex Salmond stands poised to march south with an axe twirling around his head, much like the fearsome – and seemingly untouchable – warlord Douglas in the Henry IV plays. At the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, however, the real Earl of Douglas lost a testicle.

We will have to wait until 7 May and its aftermath to see where the Salmond blade will fall and whom it might spare. Meanwhile, given the Mayor’s virtually unstoppable return to Parliament, all leading roles now look accessible to him: whether as kingmaker, heir apparent, rebel-in-chief, or even bold usurper. From the “One Nation” mood-music that began to sound just prior to Christmas, we already know the likely outlines of his pitch. Over the course of both Henry IV plays, as often in the Histories, Shakespeare depicts the unity of the nation as a precarious fiction. Weakened by differences of rank, region, loyalty and (when the Welsh “magician” Owen Glendower joins the uprising) even language, the state threatens to splinter like an inn stool under Falstaff’s bulk. Only a supreme storyteller – as Hal will become as Henry V – can aspire to hold it together.

Modern spin doctors have nothing to teach the Elizabethan theatre about the power of “narrative” in politics. And, just now, the Mayor is the one prominent politician who can plausibly embroider his own yarns. In Henry V, the young “One Nation” ruler will swiftly gather his “band of brothers” against a continental foe. Common enemies bind a divided realm. The parade of cross-class solidarity, as the king rallies his troops on the eve of battle with “a little touch of Harry in the night”, prepares the way for an onslaught on the foreigner.

In historical truth, the glorious victory of Agincourt – 600 years ago next October – led straight into a quagmire. By 1422, Henry V was dead; by 1429, Joan of Arc had begun the expulsion of the English from France. Back home, the Wars of the Roses would ravage the land for 50 years. So much for the “reformation” that conjured the wastrel Hal into a fanatical warrior-king.

In the long run, rather than pick fights overseas, Hal might have done better to slink back to the Boar’s Head and down another flagon of Mistress Quickly’s finest sherris-sack with Falstaff at his side. However glib their act, clowns tend to do less harm than conquerors. Next year, beware repentant party-animals. Rivals as well as opponents should watch their backs whenever a would-be ruler righteously declares: “Presume not that I am the thing I was.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments