Emerging-market chaos and the Federal Reserve taper mean this might be as good as it gets for Britain’s economy

The mud hit the fan in a number of countries last week

The latest quarterly GDP growth number of 0.7 per cent was on the low side of expectations and below the 0.8 per cent on the previous quarter.

There is little sign of rebalancing, with growth concentrated in services and the South-east. Annual growth for 2013 was 1.9 per cent, nothing much to shout about, although Slasher inevitably did, in his annoyingly smug, sneering way.

Don’t forget, the evidence is that he alone is responsible for the worst recovery in 100 years; the level of GDP is at least 5 per cent lower than it would have been with more sensible policies.

In a question-and-answer session during his visit to Scotland, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, warned that he was not optimistic that GDP growth, which is being driven by dissaving, would be maintained at its current rate unless business investment and exports picked up sharply in coming quarters, which remains unlikely. The bad news is this recovery looks unsustainable.

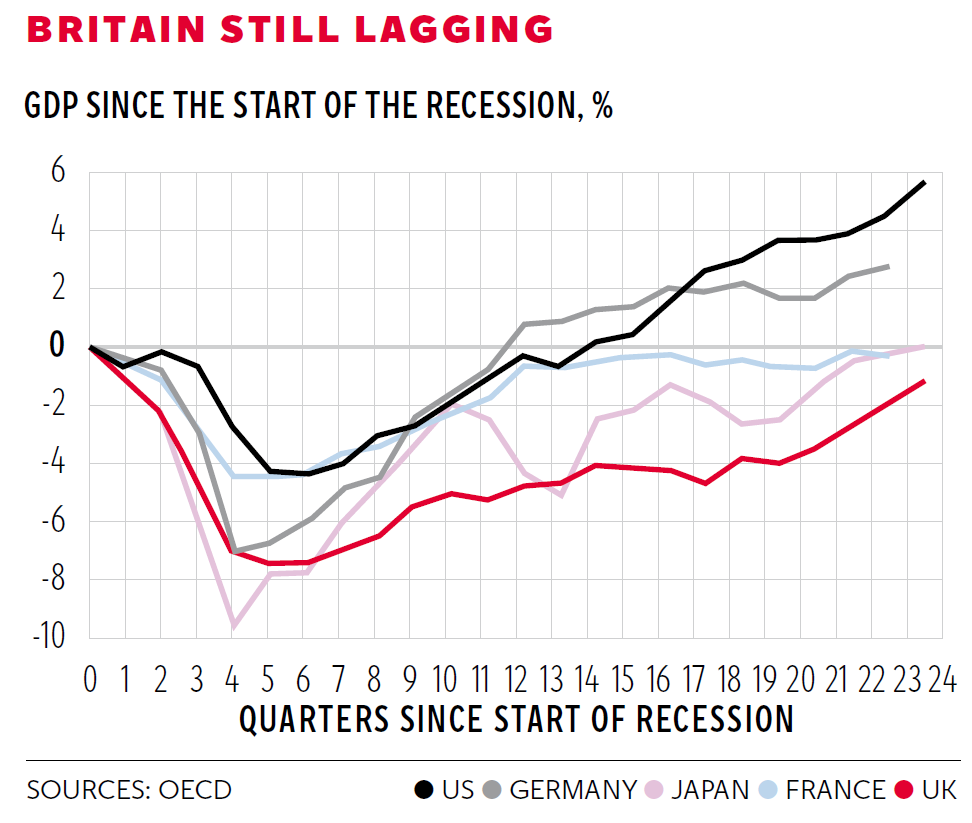

The chart illustrates how Coalition economic policies have resulted in a much slower recovery than our major competitors, including Germany and Japan, which had similar drops in output but stronger recoveries.

In Davos last month, Larry Summers and George Osborne debated macroeconomics, which was probably a mistake, given that one of them was the youngest full professor of economics at Harvard ever, a Bates Clark medal winner, which is the baby Nobel prize, has had stints as chief economist at the World Bank, US Treasury Secretary and Harvard president, while the other has an undergraduate degree in history.

Mr Summers claimed that UK performance was weak compared to the US which had exceeded the prior peak a couple of years ago.

Mr Osborne responded: “We did have a much deeper fall in GDP and for a banking sector which is the same size as the US’s in an economy a fifth or a sixth the size, the impact of the financial crisis was even greater in the UK than it was in the US. The great recession in the UK had an even greater effect and we were one of the worst-affected of the major Western economies.” Mr Summers countered with, “the deeper the valley you’re in, the faster you’re able to grow”.

The evidence in the chart appears to be supportive of the economist, especially given that the UK economy was doing pretty well in 2010, 10 quarters in, when Mr Osborne inherited it. In GDP per capita terms, which allows for the rise in population, the UK fares even worse; this is essentially unchanged since Mr Osborne became Chancellor.

The worry is that this will be as good as it gets as the world economy slows and monetary policy tightens; growth in developed countries since the recession has been bolstered by the demand from emerging economies such as China, India, Brazil and Turkey. But the mud hit the fan last week in a number of countries, starting with the release of a poor manufacturing purchasing managers’ index for China of below 50, suggesting contraction. Then it spread and interest rates rose. The Argentinian peso quickly fell 14 per cent.

Turkey surprised markets when it raised its weekly repo rate from 4.5 per cent to 10 per cent in the face of a battering inflicted on the lira, which recovered slightly after the intervention but then fell back sharply. India raised rates by 25 basis points, and Russia intervened on foreign exchanges to support the rouble. The South African central bank unexpectedly hiked rates from 5 per cent to 5.5 per cent. All of this because of fears that the US Federal Reserve was going to taper and easy money was running away.

The markets had been expecting the Fed to reduce the stimulus by $10bn (£6bn) to $65bn a month. The outgoing chairman, Ben Bernanke, did what the markets expected, and handed over to Janet Yellen to explain her plans for monetary exit at her first press conference following the Fed’s next meeting on 19 March, when a new set of economic projections will be announced.

The new committee she inherits includes four new voting bank presidents: Richard Fisher (Dallas); Narayana Kocherlakota (Minnesota); Sandra Pianalto (Cleveland), who is leaving when a replacement is appointed, and Charles Plosser (Philadelphia). The committee has lost three dovish members, including Mr Bernanke, who was attending his last meeting, Eric Rosengren (Boston) and Charles Evans (Chicago), so may well be more hawkish than the previous one. Two new members have been nominated and await confirmation by the Senate (Stanley Fischer and Lael Brainard).

Ms Yellen, who will be sworn in on 3 February, will have major challenges on her hands, not least because of the ongoing turmoil in emerging markets. It seems unlikely she can just ignore it and plough on regardless, reducing the amount of monetary stimulus without taking account of increased market volatility. The Fed’s actions have already come in for criticism from Raghuram Rajan, the governor of India’s central bank, for ignoring the plight of the developing world. Will the Fed raise rates before it reduces the stock of assets it holds? Will it continue to reinvest the principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in those same securities? And will it roll over maturing Treasury securities?

Communication is going to be an ongoing challenge – especially in relation to forward guidance – so the markets understand the Fed’s exit strategy. There is very little economics to help her: the Fed is going to follow the data from the labour market and inflation, both of which still indicate the need for further stimulus, but at some point they will signal a halt. In the latest data release, unemployment fell, but only because of even bigger movements out of the labour force rather than into jobs. So the picture may be a murky one. Of interest also will be Janet’s testimony in front of Congress and how she deals with the many Republicans who distrust the Fed and want to take away many of its powers. Previous Fed chairmen have largely been dictators and I don’t expect this to change; Janet is no shrinking violet. I wish her all the best. I am a big fan.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies