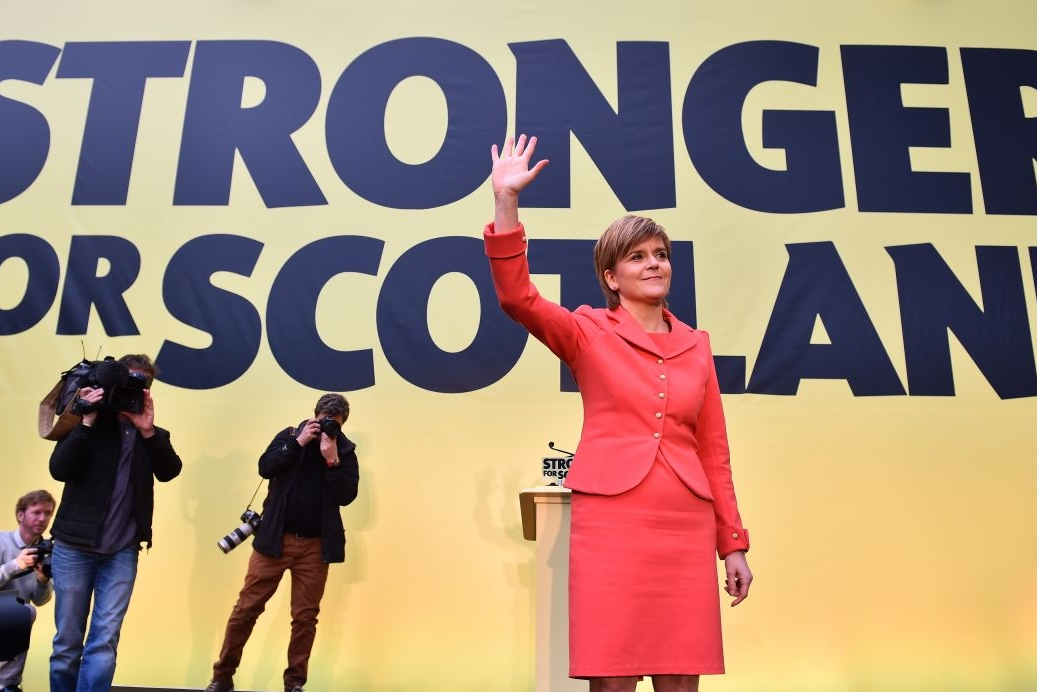

General Election 2015: If Nicola Sturgeon is such a threat, how is it she’s so popular?

For all the fury of Tory newspapers fearing the election of an administration that would not pay homage to their editors and owners, parliamentary arithmetic is set to prevail

The most talked about leader in the election is not David Cameron, nor Ed Miliband, the two potential Prime Ministers. Nick Clegg hardly gets a look-in. The SNP leader, Nicola Sturgeon, commands the headlines even though she is not even standing.

In one respect, and I mean this as a compliment, Sturgeon reminds me of Ken Livingstone in her calm composure while all around her seethe with fury. While Livingstone’s opponents reddened with rage, at his peak he won elections and seemed entirely unfazed by the waves he caused.

On Sunday Andrew Marr’s guests were Cameron, Vince Cable – an important figure in the post-election context – and Sturgeon. It was Sturgeon who made all the headlines. In her wake, Cameron suggested that what she had said was potentially alarming for the country. The Tory newspapers portrayed her as the most dangerous woman in the UK. As for Sturgeon, she was next seen launching her party’s manifesto, as if unaware that she was the cause of soaring blood pressure.

What she had said in her BBC interview on Sunday and repeated at yesterday’s manifesto launch was a statement of the obvious. Sturgeon made clear that in a hung parliament an army of SNP MPs would hold some sway over a government. This should be beyond dispute and would be true if there were a fragile minority Conservative administration in power. In such circumstances the SNP could combine with other opposition parties to make Cameron’s life even more hellish than it is already doomed to be as he renegotiates the UK’s membership of the EU.

Of course, the SNP would exert potentially hellish influence over a minority Labour government too. Miliband would be more regularly dependent on its support and there would be some genuine common ground in terms of policy. Yet the relationship would be of the most ambiguous kind. Miliband can hardly say to Sturgeon in the immediate aftermath of the election: “Thanks for destroying my party in Scotland. We look forward to working with you over the next five years.”

For all the fury of Tory newspapers fearing the election of an administration that would not pay homage to their editors and owners, parliamentary arithmetic will prevail as it did in February 1974 when the incumbent Prime Minister, Ted Heath, tried to form a government. After he had failed to do so, Harold Wilson became Prime Minister. He had the numbers to win a Commons vote on his first Queen’s Speech, even though he had won fewer votes in the election than Heath.

Wilson called another election in October and won a tiny majority. Now we have fixed-term parliaments, one of the many radical reforms rushed through by the Coalition in its reckless early phase. Do not expect another election soon.

For all the focus on what Sturgeon would demand of the next UK government, her party’s position is relatively clear. She would not support a Conservative administration under any circumstances. She would support Labour on a “bill by bill” basis. Her party would not be part of a coalition. We know much less about what the Liberal Democrats might do. Unless the Conservatives or Labour are the biggest party by a considerable margin, there will be much more internal angst in Clegg’s party about how they should act than there was last time. From 8 May they will have bigger decisions to make than the SNP, which has already made them.

For now I do not blame Clegg or any of the leaders for refusing to get involved in detailed speculation. Friday 8 May is another land. No one knows what form the land will take. All they can do is prepare for various circumstances. This time, unlike in 2010, the bigger parties are getting ready behind the scenes for the likely negotiations.

In terms of their public role, the party leaders have a very different task between now and the election. Their duty is solely to maximise their support. A senior Conservative, with smart strategic insights, tells me that he fears his party’s relentless portrayal of Miliband as being in the pockets of the SNP will appeal to the core vote and no further.

I suspect he is correct, partly because if voters in Scotland elect SNP MPs this is a democratic outcome that all the other parties must accept, however awkward. In the meantime, it is Labour rather than the Conservatives, a puny force in Scotland, which is in a battle against the SNP, as far away from an SNP pocket as it can get. The comparison between Sturgeon and Livingstone also explains the limit of the pitch. Voters never loathed or feared Livingstone as much as his opponents had assumed they would. They saw a calm figure who was supposed to be the most dangerous man in the UK and in quite a lot of cases were not frightened by him. Now voters read that Sturgeon is the leader who endangers their lives and then see a composed, articulate figure who is a popular First Minister. She is not easy to loathe, even as she induces rage across the nervy political spectrum.

Nonetheless, I had assumed the rise of Sturgeon’s SNP would hit Miliband and boost Cameron for the obvious reason that her party threatens to slaughter his. The Labour leader’s messages are also blurred by speculation about a possible arrangement with the SNP. Still the Conservatives fail to make headway. So far, Cameron seems a little ghostly in the campaign as he puts the case for reheated Thatcherism, yesterday offering non-Scottish voters protection from the consequences of a devolution settlement he was supposed to support. As he does so, most other leaders debate how to move on from the distant era in which Margaret Thatcher ruled the entire UK in landslide Westminster parliaments. This is a strangely compelling campaign.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies