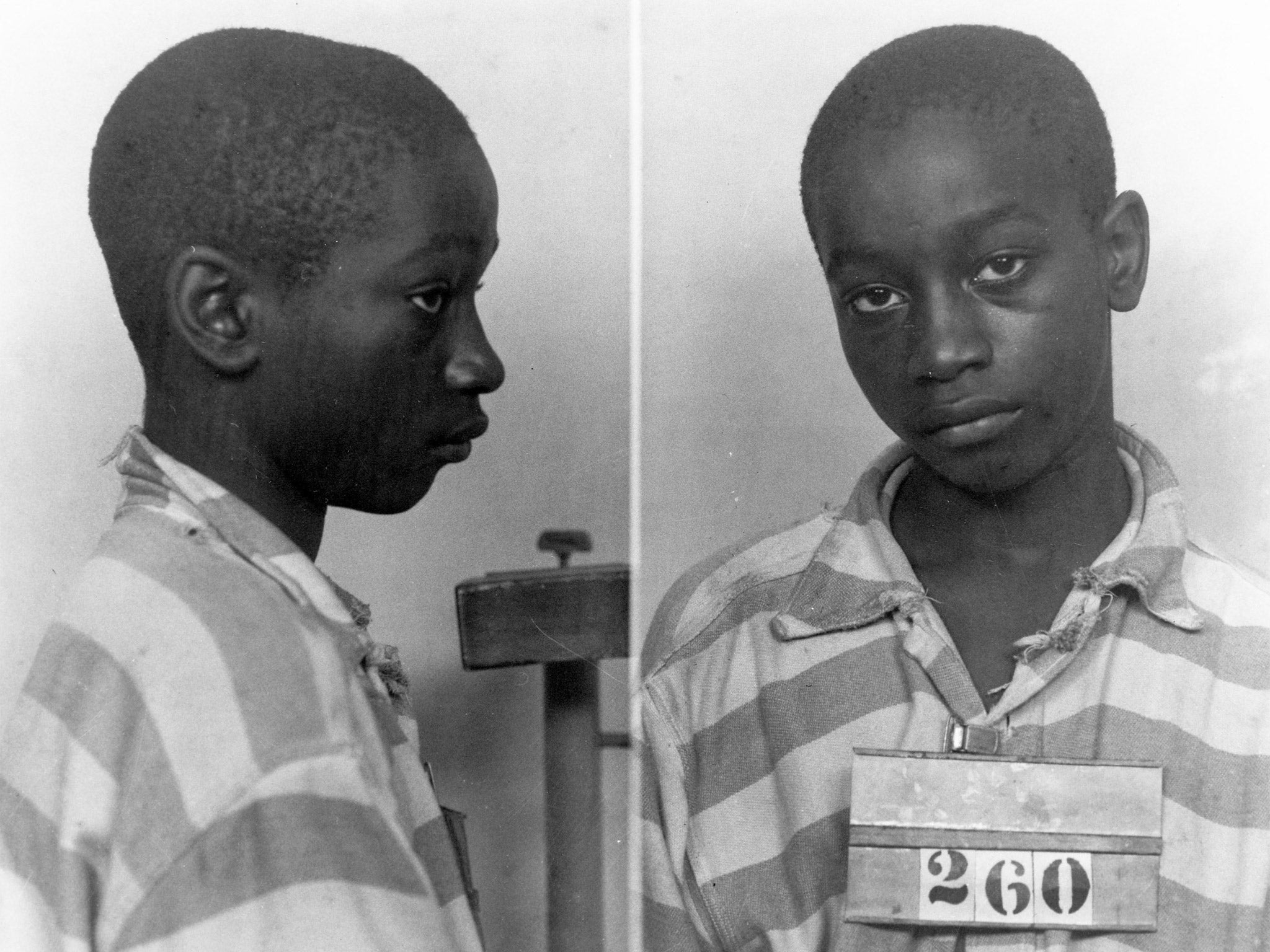

George Stinney: Even if the executed 14-year-old is pardoned, it would be wrong to suppose capital punishment has become more 'humane' since 1944

Endemic racism, of course, remains. And neither have our killing methods 'improved'

Seventy years ago the State of South Carolina acquired a dubious distinction: George Junius Stinney was executed at the age of just 14, becoming the youngest person put to death in the United States in the twentieth century. Much is made of the fact that he was so young and so small: he had to use his Bible as a booster seat and his feet were dangled as he could not reach the floor. The leather mask was too big, and slipped off when the first 2400 volts hit him, revealing his agony as he died.

Even advocates of the death penalty look back on Stinney’s death with some remorse – things were, we are told, so much less sophisticated back then. Seventy years on, his family is seeking a posthumous pardon, based on evidence of innocence. It would seem that he was a victim of local racism, when the bodies of two young white girls were found in a drainage ditch and his family run out of town so they could not help stave off an injustice. Of course, a pardon will do Stinney little good now, but are we so much more civilised in our ‘modern era’?

Of course, the racism still remains. I had to walk into the gas chamber with Edward Earl Johnson in Mississippi – a nightmare recorded in the BBC documentary Fourteen Days in May. Edward was a black teenager accused of killing a white police officer in our modern world. Edward was a victim of some very similar racism: I only represented him for the last, desperate three weeks of his life, and I learned after he had died in the swirling Zyclon B that a woman had been with him at the time of the crime. I asked her why she had not gone to the police. She said she had, but they told her to mind her own business. Edward’s black trial lawyers had been too intimidated to go to the country where the murder took place to investigate his claim of innocence.

Perhaps one reason that Stinney could not prove his innocence in 1944 was that he had no time: South Carolina took just 81 days from his arrest to his execution. Compare this to modern times: Thomas Knight was executed on January 7, 2014. He was originally sent to death row in 1974, when he was only 18 himself. In other words, he spent 44 years waiting to be executed – more than two thirds of his own life, and three times the length of Stinney’s. Can it be said that we are more civilised when we make people wait for decades, their cell lights dimming once a week as the Electric Chair is tested, before they are finally strapped down for death?

Knight had plenty of time to prove his case. But would our ‘modern courts’ have let Stinney off just because he did not commit the crime? The simple, sorry answer is, no. The United States Supreme Court has held (in a 1993 ruling that still binds us today) that innocence is not actually a reason to stop an execution. Just last week I was in Miami on the case of Kris Maharaj, a British man originally sentenced to die 27 years ago. There is powerful evidence of his innocence – three members of the Colombian cartels say Pablo Escobar was behind the double homicide in the Dupont Plaza hotel in 1986 – and yet Maharaj is still in prison. Indeed, on Tuesday, the prosecutors vehemently opposed letting us compare the 19 unmatched fingerprints from the crime scene – any one of which might demonstrate his innocence beyond sensible doubt.

Most states have now rejected the barbarism of the Electric Chair – and I can assure you it was disgusting, as I watched two men (Nicky Ingram and Larry Lonchar) being tortured to death in it. But is the lethal injection needle so much better? Stinney died after four minutes of electric agony. On January 17, 2014, Dennis McGuire died on the Ohio gurney. It took 25 minutes, as Ohio had run out of the drug they normally use for killing people, so they had to experiment.. Unsurprisingly, these macabre scientists – more Frankenstein than Einstein – got it catastrophically wrong.

A few years before Stinney’s death, Mohandas Gandhi was famously asked what he thought of Western Civilisation. “I think it would be a good idea,” he replied. Until we rid the world of the death penalty, we should not delude ourselves that we have travelled very far along the path to decency.

Clive Stafford Smith is the director of the legal action charity Reprieve

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies