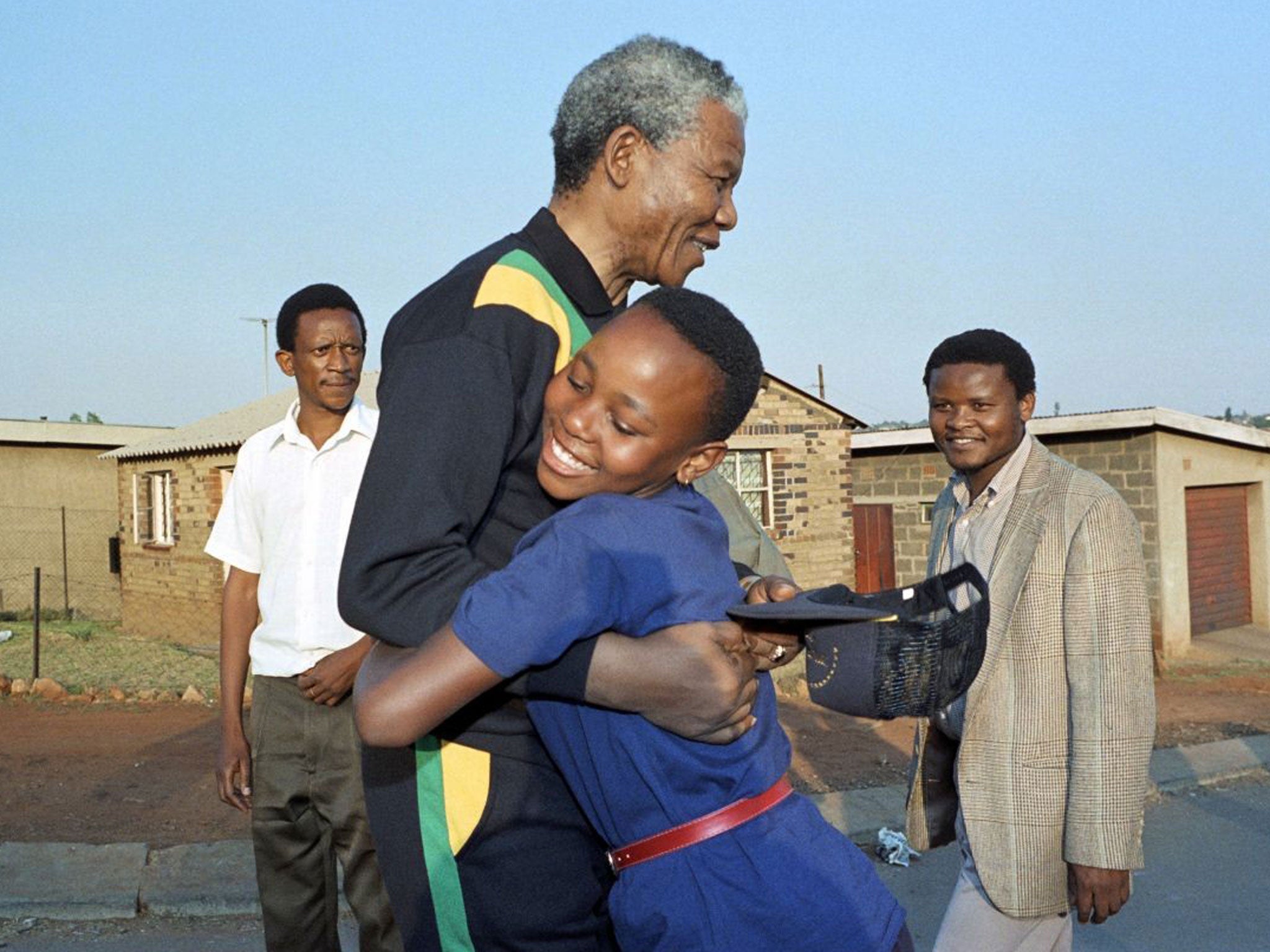

Nelson Mandela: The true embodiment of goodness

There is a spiritual dimension to the regard in which the late South African leader is held. The qualities he epitomised, of grace and charisma, have religious roots

It was always interesting, especially in his later years, to watch television footage of Nelson Mandela – greeting some visiting world leader, say, or presiding over some international event which his country happened to be hosting.

There was an affability, and a courtesy, there was a dignity that goes with the position, a happy knack – this doesn't always go with the position – of using abstract nouns like "freedom" and "liberty" with a conviction most world leaders struggle to achieve, but also something else, that made these qualities look simply routine. This was what can only be called a kind of exalted personal resonance – in part his own, in part wished on him by onlookers desperate for the personal resonance to be there – that combined two more abstract nouns, grace and charisma.

Both these words exist in deeply problematic lexicographical terrain. In fact, each of them long ago tugged free from its original dictionary definition and turned into an all-but meaningless celebrity garnish. "Grace", strictly speaking, means "the undeserved mercy of God", and "charisma", from the Greek idea of the Three Graces, "spiritual power given by God". These are not, broadly speaking, qualities that the average world leader, however puissant or magnanimous, generally attracts.

Bill Clinton, for example, was often described as "charismatic" during and after his time in office – I can remember an appearance he made at the Hay literary festival after which several of the women present who had shaken his hand declared that they would never wash their own hand again – but this is a poor definition of a roguish smile and the hint of intrigue.

Clinton, on this Olympian scale of values, would have made a good Butlin's redcoat, to use Martin Amis's famous description of his predecessor Ronald Reagan; Mandela was something else altogether. But, inevitably, given the career he followed and the work he did, the acts he performed are much less important than the values he was assumed to symbolise.

It is a cliché, of course, to observe that in an intensely mediatised world celebrated people are less important for their achievements than for the wide variety of collective and personal myths projected through them. But what was Mandela supposed to represent to the millions of people, both in South Africa and beyond, who followed his stately ascent from "terrorist" to president and communist bogeyman (at any rate to the white minority and their supporters in the west) to bringer of peace and harmony?

Again, he epitomised qualities that, like grace and charisma, have what is essentially a spiritual underpinning: wanting reparation for almost unimaginable wrongs but without recourse to vengeance; anxious for past crimes to be acknowledged (that ancient religious idea that there can be no forgiveness without the person being forgiven admitting the hurt) but aiming for betterment on both sides. One of the most widely quoted statements attributed to him on the morning after his death was that deeply conscientious: "To be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others", in which the personal becomes the communal, and the individual destiny is instantly framed in almost universal context.

It hardly needs saying that this is divinity without the divine, that Mandela achieved most of his resonance – certainly to his western admirers – by peddling a spiritual message that avoided mention of the word God: one of the most regular compliments he attracted in his pursuit of the good was that of "secular saint". In the last half-century or so the idea of the secular saint – the man or woman who embodies what orthodoxy defines as "goodness" without harping on about after-lifes or commanding intelligences – has become a staple of European political thinking: the average piece of journalism about George Orwell usually introduces the phrase by the end of the second paragraph.

At the same time the roots of the secular saint are not in the least modern. They can be found, if not in the Enlightenment – and who was going to do the enlightening if not a succession of much-admired philosophes with fluent pens? – then in the Victorian cult of the "great man", the Carlyelean, or Arnoldian or Darwinian sage who could infuse much-needed wisdom into public debate, and in the increasing absence of divine authority come up with an acceptable man-made substitute. That many of the secular saints of the first part of the 20th century were in fact practising Christians was beside the point. G K Chesterton, to take a rather obvious example, was a Roman Catholic but his moral homilies appealed to thousands of people who would never have dreamed of attending mass and regarded his spiritual views as the merest superstition.

It is the same – much more comprehensively and urgently – with Orwell, most of whose mature work proceeds from the idea that the greatest problems facing the mid-20th-century world was the vast reservoir of displaced religious sensibility floating around it and the collapse in behavioural standards that followed the weakening of religious belief. Nineteen Eighty-Four insists that totalitarianism can only flourish in societies where God doesn't exist: only this gives the totalitarian his sanction, for in his heart of hearts he knows that he is behaving badly, while also exulting in the fact that, here in a Godless world, there is no one left to punish him – either now, or, more importantly, in the hereafter.

These are questions that, with certain prominent exceptions, the modern professional atheist chooses to ignore. It is so much easier, after all, to talk about "common sense" and "liberal consensuses" without admitting that the liberal consensus has as much coherence as government planning policy and that the average human being wants desperately to know how to behave properly in an age where there is very little agreement as to what behaving properly might consist of. Hence, perhaps, the worldwide reverence of the man from Mvezo, who spent his public life behaving properly according to lights that were his own but which his onlookers grasped at as the model of exemplary moral behaviour.

Set beside him, most of the people he dealt with on the international stage looked venal and self-interested, and perhaps the most significant tribute that can be paid to him is that, like all the very best secular saints, the personal cult that formed around him was of no interest to the saint himself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies