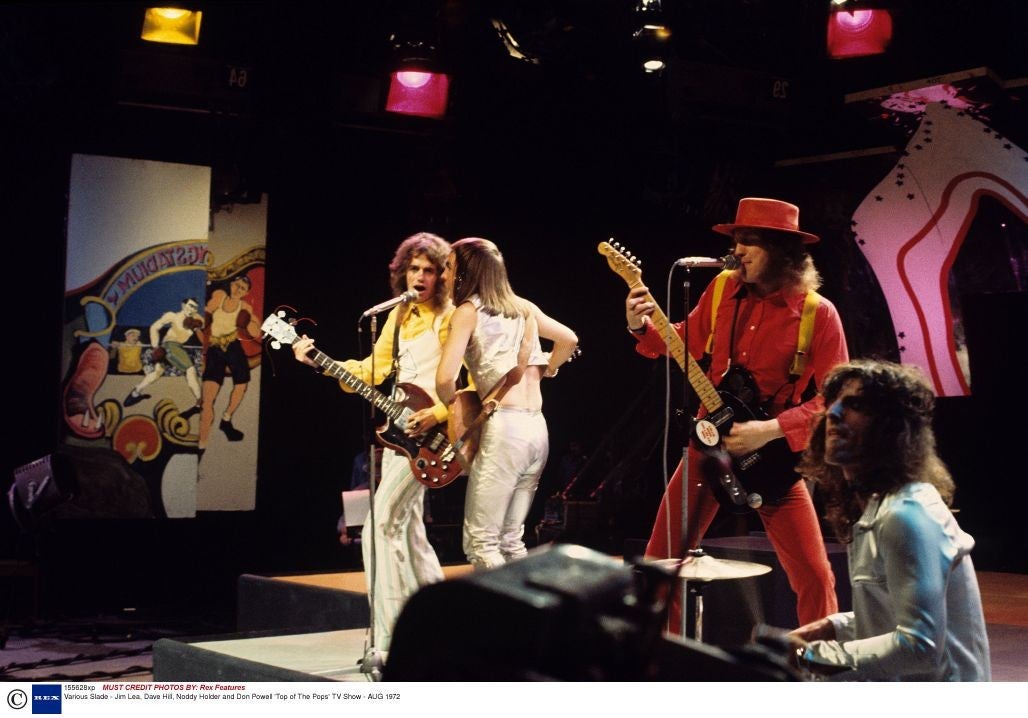

Of all the various anniversary commemorations kicked into gear by the advent of 2014 – the Great War, Bannockburn, the arrival of the Hanoverians on the British throne – one, at least, seems to have been conspicuously under-memorialised. I refer, of course, to Top of the Pops, which turns out to have made its debut on our television screens 50 years ago last Wednesday and whose cultural significance, to any one born in the last four decades of the 20th century, can scarcely be undersold.

At a rough estimate, between 1971 and the mid-1980s, when for some reason it seemed time to put away these childish things, I must have watched 750 examples of what to a teenager living on the sedate English provincial margin was a cornucopia of style, glamour and suggestiveness. My TOTP memories are half to do with situational emphasis – the long, anticipatory stake-out spent yawning through Tomorrow's World before the real business of the evening began, the warnings to friends not to telephone between 7.20 and 8pm – and half to do with the sheer oomph of the spectacle. Roxy Music unveiling "Virginia Plain" (1972); Sparks negotiating "This Town Ain't Big Enough for Both of Us" (1974); The Jam unravelling "Down in the Tube Station at Midnight" (1978): I marvelled at them all, and I can remember them as vividly as the moon landings or Margaret Thatcher quoting St Francis of Assisi on the steps of Number 10.

If this note of elegy sounds rather overblown for what, in the end, was simply a pop music showcase designed to feather the nests of the nation's record company executives, then it should also be said that the success, and ultimate demise of Top of the Pops and its paraphernalia – the inane emcees, the frantically cavorting female talent, the pompadour hair-styles – has a profound symbolic importance to the way popular music has been brought to its consumers over the past half century. To begin with, it was communal. Upwards of 15 million people watched it, most of them teenagers, and it informed the pre-adult discourse of the school playground in a manner that now seems rather startling. Had one seen the Quo play "Caroline" the previous night? Did the new Bowie single cut it? What about that blonde one in Abba, eh?

Then again, its appeal was practically universal. Your parents may not have liked the music, but they knew who was making it and could offer opinions if pressed (I can remember my father, who disliked The Beatles, giving me a lecture about the meaning of the lyrics to "Penny Lane".) Oddly, this universality stemmed from the fact that, ultimately, there was so little of it to assimilate. In fact the entirety of popular music, circa 1976, could be parcelled up into half-a-dozen categories – pop, rock (and its hobbity offshoot progressive rock), soul, disco, folk and reggae, with "world music" barely a gleam in the specimen New Musical Express reader's eye. I can still remember the shock with which I heard some work colleague in the mid-1980s describe himself as an "Essex funkster", for it advertised a taxonomic divide which I had not known to exist.

If the changes that have been wrought on popular music since the tuppence-coloured days of Noddy Holder's mutton-chop whiskers and Bryan Ferry's sneer are, at one level, merely those of classification – trying to work out what, in a teeming marketplace, one is listening to – then on another they are a pattern demonstration of the way in which major art-forms, driven by technology and changes in popular taste, mature or, depending on your point of view, diminish. While old-style pop was, broadly speaking, communal, new-style pop, leaving aside the experience of attending a live concert, is individual, listened to, by and large, in isolation, cutting you off from the world around you rather than connecting you up. While old-style pop was universal, with the average top 10 single selling in six figures, and Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon a fixture on every male teenage record rack, new-style pop is terminally fragmented, with no real mainstream and sub-genres beyond count.

In undergoing these serial mutations pop has, naturally, been prey to some of the pressures which affect more up-market art-forms. Here, traditionally, a burgeoning medium reaches an early high-point of achievement, and then spends the later stages of its development consolidating itself, diffusing its resources, experimenting and falling apart. The English novel, it might be argued, reaches an initial peak in the late 1840s with Dickens, Thackeray and the Brontës and then goes on to pursue half-a-dozen alternative courses. The hot-house conditions in which pop music thrived, since the birth of rock and roll in the mid-1950s, meant that these changes happened with lightning swiftness. The Beatles, to particularise, presided over a brief moment in which the hipster's Bible and the housewife's choice were essentially the same thing.

In their wake, pop music history has tended to consist of a series of stand-offs between a genuinely popular culture forcing its way up from the streets and the mass-market priorities of the record companies – brief and bloody entanglements, after which the biz generally re-exerts its stranglehold. The rise of YouTube and social media may have complicated this process and reduced record company profits, but for some reason Adele and One Direction still top the charts while the left-field and the avant-garde go more or less unheard. Worse, given that the form has been in existence for nearly 60 years, nearly all the trappings of inter-generational conflict with which it was once invested have been blithely dispersed. Here in my early fifties, I like most of the music my children like, and their Christmas presents to me included CDs by the Arctic Monkeys, PJ Harvey and Mogwai. Teenage revolution this definitely is not.

Music aside, the social implications of these changes for the kind of people we are and the way in which we respond to popular art are immensely depressing. Only this week I received an advance copy of a wonderful book entitled A Brief History of Whistling. The authors, John Lucas and Allan Chatburn, begin with the observation that no one these days whistles in the street. And yet 40 years ago the average thoroughfare resounded with people trying out the songs of the day. My father used to roam the precincts of Norwich Cathedral Close whistling passages from obscure choral works in the hope of stirring a response from the cathedral organist. No one whistles, because music is disseminated in other, more private ways. But a tune you can whistle in the street – the Old Grey Whistle Test, to borrow the title of another defunct BBC music show – has the advantage of bringing people together rather than driving them apart. So, in its way, did Top of the Pops, which for all its absurdities, not to mention the Savile-esque taint that now disfigures nearly all recent light entertainment, seems quite as ripe for commemoration as several of the more edifying marker-flags of human existence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments