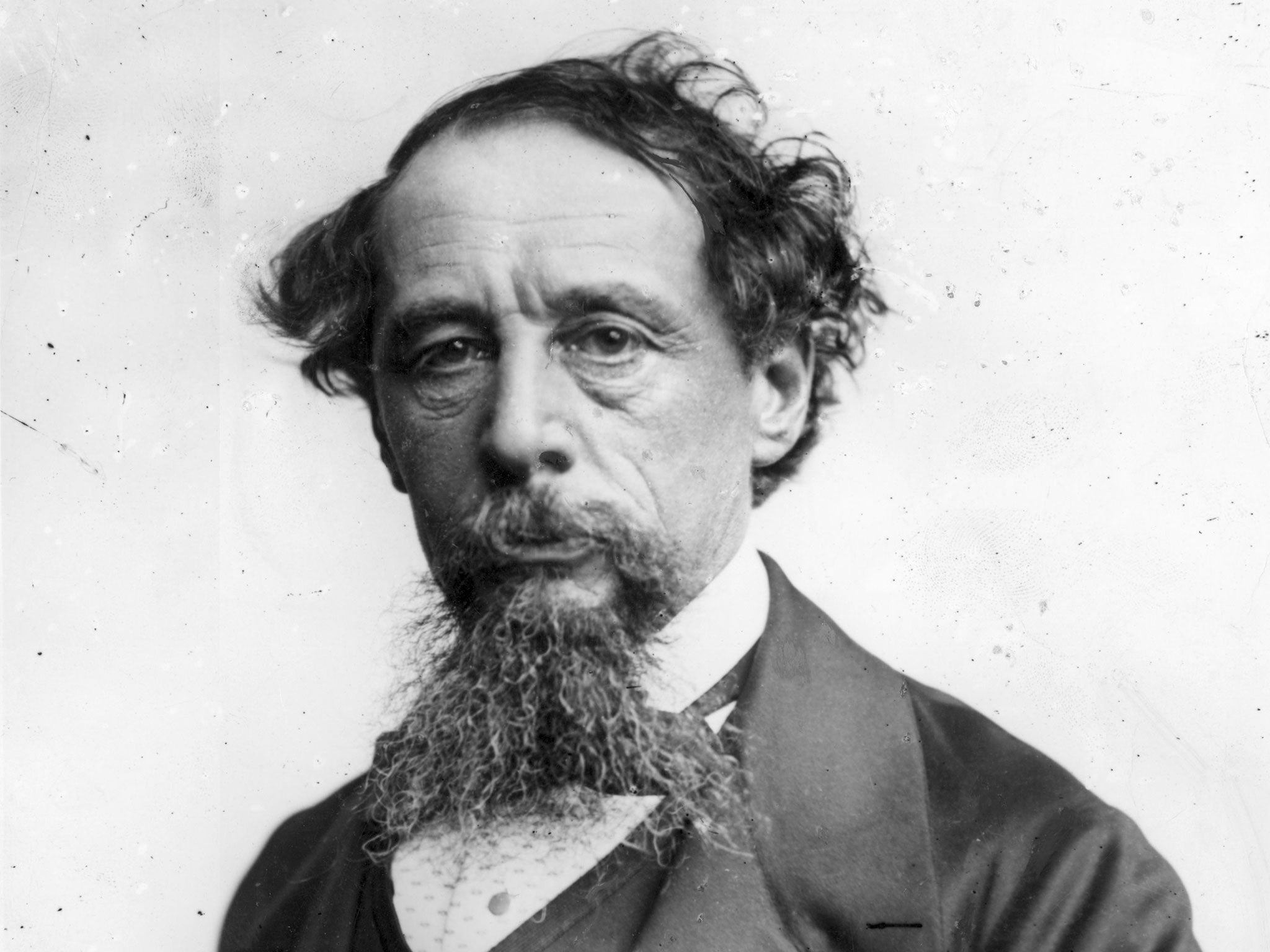

Not since the days of Dickens has middle-class prosperity so relied on family bequests

Osborne's reforms to Inheritance Tax have lawyers rubbing their hands with glee

You will probably know the scene from a throng of Victorian novels, corny melodramas, family sagas and murder mysteries. In the hushed parlour, the family solicitor gravely reads a will. One after another, the time-bombs laid by the wealthy but mischievous deceased explode. The vain wastrel heir – cut off without a penny! The loyal retainer – set up in a cosy cottage with a handsome annuity! The penniless great-niece – left enough for her to marry her humble swain, but not so much to tempt them from a life of honest toil.

Not only potboilers turn on the will, but many classics too. Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, to pick just one, pivots around the legacies – or lack of them – that fix the destinies of schoolfriends Becky Sharpe and Amelia Sedley. With her husband killed at Waterloo, Amelia and her little son at length escape their penury thanks to the deathbed generosity of her father-in-law. And what was the name of the spendthrift dandy who left his family so short of funds? Captain George Osborne.

Last month, another George Osborne won applause when, in the Summer Budget, he raised the threshold for Inheritance Tax (IT). By 2021, after a series of increments, the combination of a raised personal exemption and a new “family home allowance” will mean that couples can together leave an estate of £1m without liability. It clearly took some fiscal prestidigitation to reach that magic figure. Still, the Government can now claim that the number of estates paying IT will, by 2021, fall from the pre-reform estimate of 63,000 to 37,000.

Now, what is that faint chirruping we can hear in the distance? Not an August plague of cicadas, but the sound of lawyers rubbing their hands in glee. As loudly as possible, the Chancellor has signalled that he wishes the profits to some families from the selective rise in property values to cascade down the generations without state impediment. Over the past two years, house-price hyper-inflation has in certain areas so far outstripped wages that bricks-and-mortar can in theory “earn” three or four times a full-time job: on average, £143,000 more than median income in Hammersmith and Fulham, or £102,000 in Wandsworth.

True, these districts will have the greatest number of estates with a value above the new threshold. Even so, Osborne – almost as reckless as his fictional namesake – intends that the extra privilege now bricked into British society by a lopsided property boom should pass down to grateful heirs with minimal interference. Forget that deceitful guff about “hard-working families”: just propaganda for the hoi polloi. The real British disease is that a few million of the luckiest baby-boomers think they will and should earn a fortune for themselves and their offspring by sitting on their fattening assets.

Beware: this model of conveyor-belt inequality depends on hitch-free legal transfers, without snarl-ups within the probate process. This is where the will makes its fateful return. Mix almost a decade of stagnation in real wages with near-zero savings rates, plummeting pension-fund returns and a crazy spike in the price of some residential property, and you have a blend of factors that will plant family bequests as close to the heart of middle-class prosperity as in the days of Dickens.

Meanwhile, the rate of home ownership in Britain has fallen to its lowest in 29 years. Inheritance – of real estate, and of the wealth locked up in it – will matter even more. As the role of inter-generational legacies expands, so greed or need will drive more squabbling heirs to court. Complex family structures, with the proliferation of step and half-siblings, may further stir the litigation pot. Hence those serene solicitors and blissful barristers.

A few days ago we saw evidence that the contested will has recovered its old bite. After 11 years of verdicts and challenges – express delivery, by Victorian standards – the Court of Appeal decided that Melita Jackson had wrongly refused to make any provision for her estranged daughter Heather Ilott. In a ploy familiar to connoisseurs of disinheritance, Mrs Jackson had in 2004 given £486,000 to three animal charities. Mrs Ilott will now receive £164,000.

To outsiders, these post-mortem prolongations of rifts between parents and children can look more amusing than distressing. We can giggle over the monstrous plutocrat who – in the manner of New York’s “Queen of Mean” hotelier Leona Helmsley – prefers a chihuahua to a child. Or we applaud Golda Bechal, who in 2004 left £10m to the owners of a Chinese restaurant – close friends for decades – rather than her outraged nieces and nephews. In that case, Mrs Bechal’s only son had died at 28. Try to imagine the bitterness of a breach that remains beyond reconciliation at a parent’s death, however, and the courtroom farce begins to feel like tragedy.

The tradition of English law gives special potency to these posthumous blood-feuds. What lawyers call “testamentary freedom” has in principle meant that a will-maker can do what they damned well like. Eccentricity, folly, even malice do not themselves invalidate a will. In 1873, probate judge Sir James Hannen thundered that a testator “may disinherit … his children, and leave his property to strangers to gratify his spite, or to charities to gratify his pride, and we must give effect to his will”. Beloved cats, donkeys and parrots, rejoice!

Other jurisdictions – France, Germany, Ireland – in contrast assume that children retain some right to partial if not full inheritance. Here, only firm proof of outright irrationality and insanity – not being “of sound mind” – could trump that cherished death-bed licence. However, in the 1930s pressure for reform – led by the feminist campaigner and social reformer Eleanor Rathbone – began to dislodge this absolute power.

In 1938, the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act installed some restraints on “testamentary freedom” in order to safeguard widows, widowers, and dependant or disabled children. A legal scholar fretted at the time that “the Englishman’s unlimited freedom to cut off his children without a penny is gone”. By 1975, the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act had fortified the courts’ ability to overturn or modify wills that shut out vulnerable relatives. With capricious or spiteful legacies, the balance of proof has gradually shifted. This week’s judgment in Ilott v Jackson will encourage more disappointed heirs to take the most wilful wills to court.

In which case, the thickening ranks of celebrities who now insist that their kids should fend for themselves should place a call with a hot-shot counsel now. Sting, Nigella Lawson, Lenny Henry, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Simon Cowell: avowals that one’s progeny should learn to get by without family riches have become as modish as a table at the Chiltern Firehouse. This tough love, we have to assume, is entirely consensual. Not so with the target of the so-called “Rinehart Paradox”, named after Australian mining magnate Gina Rinehart.

Mrs Rinehart, Australia’s wealthiest citizen, sought to keep her adult children’s hands off the family trust until 2068 (love your sense of humour, mum). She argued that they lacked the “capacity, or skill or knowledge, experience, judgement or responsible work ethic” to control it. Two challenged her. In May, they managed to seize the trust from their own mother.

In the future, this commotion may not only shake stars and tycoons. In London and much of southern England, the explosive formula of goldmine houses, stalled careers, layered families and shrunken pensions could bring a bonanza for the briefs. Housing activists lament that the transmission of inflated property across the generations will entrench the gap between the landed haves and the landless have-nots. They should bide their time and look forward to the pleasures of schadenfreude. We have centuries of evidence that the British propertied classes love nothing better than to squander their family wealth in arcane and ruinous legal tussles. Remember the outcome of Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Dickens’s Bleak House? Yes, Jarndyce and Jarndyce, that “scarecrow” of an inheritance dispute “so complicated, that no man alive knows what it means”.

Readers who think of Dickens as a prose cartoonist ought to know about one of his models for the case. Jennens v Jennens, which arose from the unsigned will of the “Acton Miser”, crept all the way from 1798 to 1915: 117 years. When Dickens was writing Bleak House the suit was scarcely middle-aged. At the close of his testamentary wrangle, the lawyer Kenge is asked: “Do I understand that the whole estate is found to have been absorbed in costs?” “Hem! I believe so.”

“Absorbed in costs”: Take care, comfy boomers, as you calculate the princely gains on that suburban semi. Think of Ilott v Jackson, if not Jarndyce and Jarndyce. Jurists warn that this week’s judgment has strict limits and does not mean that “forced heirship” has come to England. Disgruntled children – and opportunistic lawyers – may not see it quite that way. So make sure that every link in the chain of kin remains secure, lest a Victorian fate wreck your post-mortem plans with the sort of zombie lawsuit that “stretched forth its unwholesome hand to spoil and corrupt”. The Dickensian will is rising from its grave.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks