Some of the world's most powerful CEOs are taking on capitalism, and they need our support

At some of the world's biggest corporations, an Occupy-style struggle is taking place behind closed doors

Not so long ago, the struggle for and against rampant, exploitative capitalism was fought between the workers and their employers.

But with the collapse of collective bargaining, that battle is over.

The struggle now is within multinationals themselves. On one side there are the progressive reformers, often a do-gooding CEO. And on the other side there are the stalwarts of the free market, usually the shareholders, who will do anything to maintain the broken status quo.

"I don’t think our duty is to put shareholders first. I say the opposite". These aren’t the words of an Occupy activist, but Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, one of the world’s largest multinationals, with annual global turnover of $50bn. According to Polman, the current capitalist system is broken. “How long can we steal from the future?" he has been quoted as saying. "Our system is a great system, but it’s not designed to function long term [...] Capitalism has been the worst form of economic system – except for all the others that have been invented.”

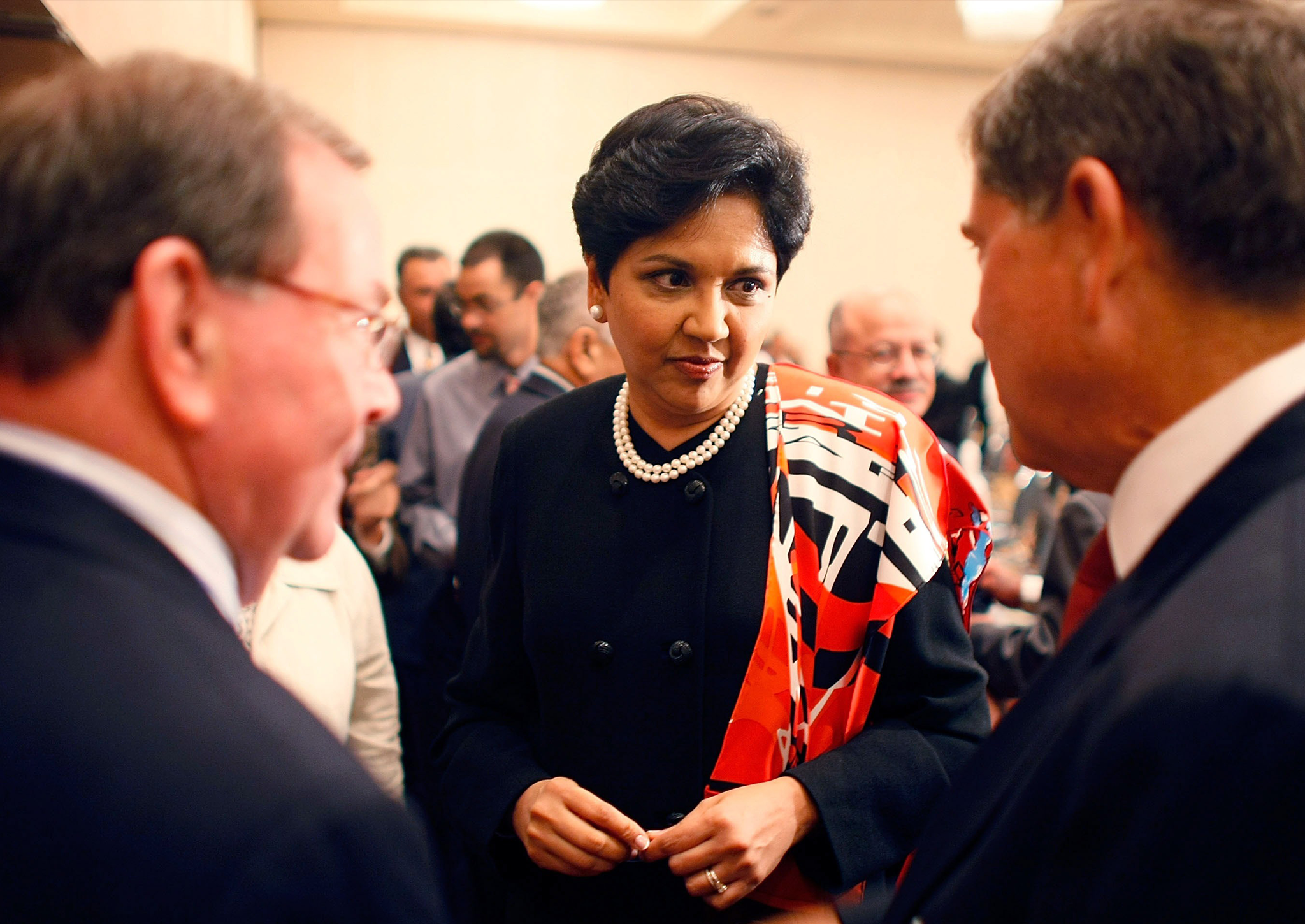

Over at PepsiCo, another of the world’s giant corporations (and one of largest contributors to the obesity endemic) CEO Indra Nooyi says: "I believe we need to attack obesity. Let us be good industry that does 100 per cent, not grudgingly, but willingly."

Polman and Nooyi aren't bleeding heart liberals from NGO backgrounds, parachuted in for some empty soundbites. For their entire lives they've obediently worked their way up the corporate ladder.

Their statements – considered radical given their positions – point to a fundamental shift in global corporate dynamics, and one that will increasingly come to be the new struggle within the global economy.

This struggle once took place on the picket line, but it's now fought behind closed doors, at hushed general meetings. But it’s still a showdown every bit as fierce, with far-reaching implications for all of us.

The outcome will change nothing short of the moral tenor of capitalism for years to come: everything we buy, how it’s made, and how much it costs; the food we eat and how its grown. It's politics, without politicians, or the public, having a say.

So how does this struggle pan-out? One of Indra Nooyi’s first decisions on taking over Pepsi was to declare that she wanted the company to fight obesity by becoming "post-sugar", much in the same way BP aimed at going "post-petroleum" since global warming became such a burning issue. Nooyi started by hiring the WHO’s Derek Yach, and diversified Pepsi’s portfolio into a host of healthy brands such as Quaker Oats.

At Unilever, Polman showed his reformist cards by championing "slow money" – long-term investment in small sustainable businesses rather than chasing relentless quarterly profits.

He was tackling the beast head-on. Quarterly reporting (QR) is the central doctrine of short term capitalism. If you’re shareholder, it's the only thing that matters. If you’re a reforming CEO, it’s the single greatest obstacle to meaningful reform. Both Nooyi and Polman have declared war on QR, and seen an open revolt from their shareholders.

All of this marks a huge shift from the classic, 1950s model of the corporation as a "family", overseen by a quiet father figure (CEOs back then were always male). By the 1980s, a new type of leader was required for the explosion of the free market, and in came the “captains of industry”. CEOs became pop stars, splashed across the cover of Forbes and The Economist, and were hailed as geniuses for their ability to slash costs.

Over here in the UK, the cult of the CEO began with Richard Giordano, who came from America to take over the privatised gas company BOAC in the 80s. I met Richard at The Dorchester, and he told me that after his arrival in Britain, everything changed. The CEO was no longer “in it together” with his employees. His job was to align himself with the interests of the shareholders, and target profit above all else.

But then something happened. Global warming. And then obesity. And financial scandal. Multinational companies – especially those directly implicated in the creation of climate change – needed an image change. A new breed of CEO was required.

It was one that would talk the language of concern, and be neither aligned to the workers nor the shareholders. Like a Miss World contestant, the new CEO’s main job was to say they wanted to better the human race, so the company could be seen to be ticking the new biggest box for the public.

Deep within the marketing departments of the corporate machines, it was hoped people like Polman and Nooyi were just for show, and didn’t believe what they said. But then the penny dropped that they actually might. From that point on, the battle began.

They might seem like masters of evil (especially to the left-wing among us) but CEOs could actually be our best hope of taming capitalism. With the influence of corporations on our political system growing alongside their profits, it's time for us to rethink our approach.

Progressive people might find their energies better spent identifying the good guys from the bad guys within the corporate world, and getting the hell behind them. Because unlike politicians, it's the radicals within the machine that wield real power.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments