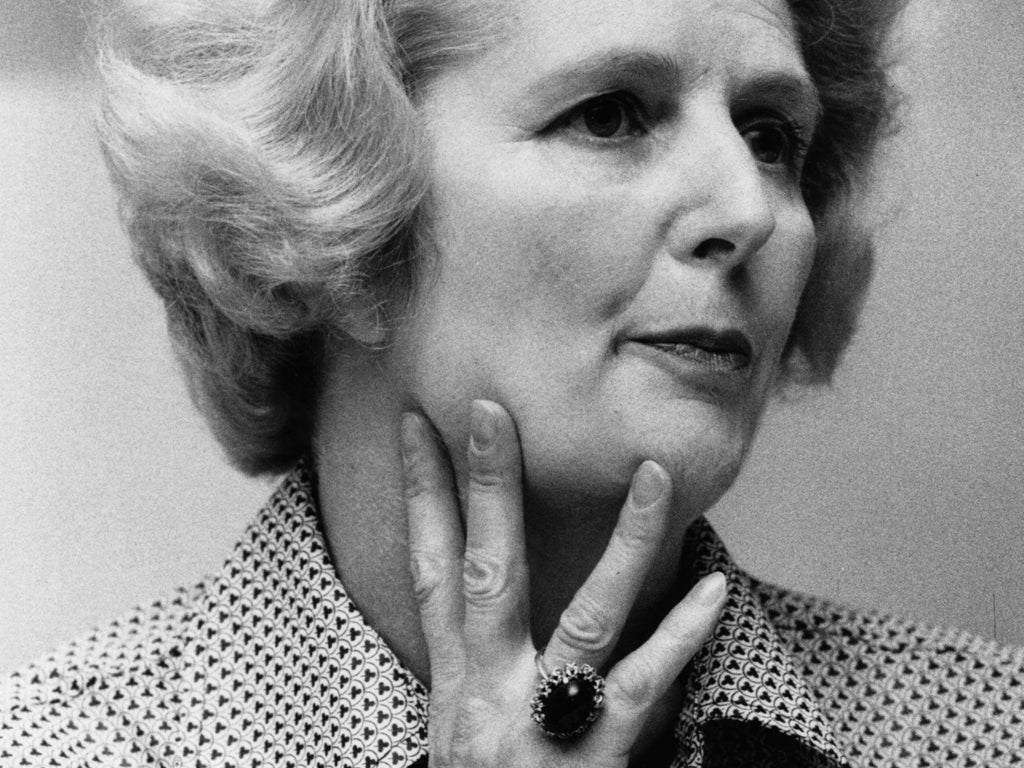

Shirley Williams: How Margaret Thatcher changed Britain

She used gender to her advantage until hubris brought her down

Margaret Thatcher will go down in history as one of the 20th century’s most remarkable Prime Ministers, surpassed only by David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, both of whom were leaders during great wars.

She was not the cleverest or most brilliant of the great politicians of her generation, but she was unquestionably the most single-minded, the most determined, and the equal of them all in her passionate and immutable convictions.

Those convictions were born of her upbringing in the disciplined, thrifty, small world of an isolated town, Grantham in Lincolnshire. The passion came from her determination to succeed, and from her experiences of a war in which Germany was the enemy and the United States, whose airfields spread over the Lincolnshire wolds, the ally.

There were many obstacles to overcome. Her father was a respected alderman, but was neither wealthy nor, outside his own town, influential. He took the young Margaret with him to local meetings, and local government was her political nursery. By sheer commitment and hard work, she managed to get to Oxford University, teaching herself Latin, an entry requirement, and polishing up chemistry, her special subject. Once there, she devoted herself to politics, becoming president of the Oxford University Conservative Association, only the second woman to achieve that position.

In its imperturbable way, Oxford remained unimpressed. “Margaret has a second-class mind,” the principal of her college, Somerville, opined, the ultimate University put-down. But Janet Vaughan, like many other academics, failed to recognise that success in politics has much more to do with character than with mind. Margaret Thatcher’s character had been forged in a series of personal battles within a society that failed to value her.

She was a woman at a time when there were statutory women – the indispensable sole female member of the Cabinet in governments pretending to be modern. She was a Cabinet minister in a Cabinet – that of Ted Heath – where she was not encouraged and sometimes not even allowed to express her own viewpoint. She was a fall guy for the Treasury’s expenditure cuts, for it was Anthony Barber, not Margaret Thatcher, who abolished free milk for school children; yet it was Margaret Thatcher who took the blame for it and was nicknamed Thatcher the Milk-Snatcher.

She was sensitive to such attacks, indeed upset by them. But they tempered her steel further. She thrived on argument, conflict, and confrontation. And as she grew more and more powerful within her own Government, she shaped it to be more compliant to her own views and wishes, often bypassing or disregarding the Cabinet and reshuffling ministers so as to lose the Tory moderates, the “wets”.

In all this, the great challenge of her first administration, the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands, 8,000 miles from Britain, was crucial. Her decision to recover the islands was breathtaking, a huge and incalculable risk. The ultimate victory in the war was a much closer-run thing than most commentators realised. She was driven by her innate patriotism, but also by the sense that she had nothing to lose. She was deeply unpopular after the savage Budgets of 1981 and 1982. Unemployment was burgeoning, and hundreds of small businesses were facing bankruptcy. Yet, within two months, her position had become unchallengeable; she was the Boudicca of the modern world.

The Falklands victory led her on to the domestic challenges, the miners’ strike and the power of the unions. Mrs Thatcher was no leader of the Light Brigade, though the Falklands looked a bit like that. Now, at home, she played her cards cunningly, making sure that she only took on the miners when her government had built up large stocks of coal, large enough even to outweigh her equally committed opponent Arthur Scargill – committed, yes, but nothing like as clever.

By the time Margaret Thatcher had won her third General Election, albeit against a divided and fractious Labour Party, she seemed unassailable. She had defeated the miners and curbed the trades unions, partly by law, partly by unemployment. She came to believe she could not be mistaken.

Stubbornly, and despite warnings from her Cabinet colleagues, she insisted upon bringing in the poll tax, based on her simple view that everyone should pay the same for local government services. Hubris, which waits in the wings for the great leaders who bestride the world’s stage, brought her down. She regarded those who warned her, and those who abandoned her, as traitors and enemies. But they had had enough of her dominance, her unwillingness to listen. In the end, they found the courage to tell her so.

What was the secret of this extraordinary woman’s power? Sir Percy Cradock, her foreign affairs adviser, quoted in Professor Peter Hennessy’s book on Prime Ministers, said “the combination of femininity and power intrigued and excited her male interlocutors, from President Mitterrand to Anthony Powell…”. Maybe. With Gallic sensitivity, President Mitterrand used to bring her flowers when they met. In private, he admitted to his friends that he found her very attractive. She had, he said, the eyes of Caligula, but the mouth of Marilyn Monroe.

I find a slightly different explanation for her dominance over her Conservative Cabinet – and it is worth noting that she never promoted any other woman to be a member except Baroness Young who was distantly ensconced as leader of the House of Lords and so in no sense a rival. Most Conservative MPs of Mrs Thatcher’s generation had been brought up by nannies and then sent to boarding school, where they encountered another set of authoritarian women – matrons – who had to be obeyed. That early training made such men uneasy about challenging a woman leader and unsure about how she might react.

In her final years as Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher became somewhat monarchical. Like Queen Elizabeth I, she had a private court – an admired counsellor or vizier in William Whitelaw, of whom she once said in a wholly innocent double-entendre, “Every Prime Minister needs a Willie”, a favoured squire in Cecil Parkinson, and a whole legion of young knights in cavalry-twill trousers and striped shirts who would gladly have died for her.

Mrs Thatcher had no hinterland of books or music, grouse-shooting or sailing, like other Prime Ministers. Politics was too serious a business to waste time on play. But she did have a private life which revolved around her husband, Denis, on whose humorous, detached but completely loyal support she depended, and her son Mark, upon whom she doted.

Many years ago, my husband and I saw scrawled on a ruined castle in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco the words “Sic transit gloria mundi” – so passes the glory of the world. Margaret Thatcher will long be a figure of controversy, adored by some, detested by others. History may dim her memory, but she will not be forgotten.

Baroness Williams of Crosby is a Liberal Democrat peer and was one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party in 1981

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies