The ECB brandishes a feather duster instead of a bazooka as it goes into battle for the euro

The ECB is at least consistent in always putting off until tomorrow what it should have done yesterday

Fortunately the European Central Bank isn’t listening to Andrew Sentance who argued in the Financial Times recently that it shouldn’t worry about “the false bogeyman of deflation” – actually it should.

As Paul Krugman has pointed out, “falling prices worsen the position of debtors, by increasing the real burden of their debts…debtors are likely to be forced to cut their spending when their debt burden rises, while creditors aren’t likely to increase their spending by the same amount.

“So deflation exerts a depressing effect on spending by raising debt burdens – which can lead to another kind of vicious circle, in which depressed spending because of rising real debt leads to further deflation”.

The European Central Bank in its wisdom last week cut interest rates and lowered one of its rates from zero to minus 0.1 per cent in the hope that this will prevent deflation. It is hard to believe that such a small change will do much of anything. Why not go the whole hog and, say, cut it to minus 1 per cent or even minus 2 per cent or minus 3 per cent if they really wanted an impact?

The idea was to help the periphery countries in particular by weakening the euro. The euro fell for about half an hour but within the hour had climbed above its starting level; as ever the market was underwhelmed by “not so super” Mario. As I said on a Bloomberg radio interview just after the decision, this was not a bazooka, it was more of a feather duster. It was, though, a kick in the eye for the Bundesbank, which has opposed any monetary easing despite the fact that the eurozone economy has virtually had the life squeezed out of it by both overly-tight monetary and fiscal policy.

The ECB signalled last month it was going to make a policy move. Given the need to do something it is hard to understand why they didn’t act last month, or for that matter the month before that, or the year before that or even five years before that. Ed Balls and Gordon Brown can take full credit for their wise decision to keep the UK out of the disastrous euro project.

At the press conference following the announcement, the president of the ECB, Mario Draghi, announced measures to ease borrowing constraints on the currency bloc’s smaller businesses, including providing up to €400bn (£325bn) in cheap loans to lenders. He added the central bank was stepping up its preparations for asset purchases or quantitative easing.

Given that the Fed started QE in 2008 and the Bank of England did so in 2009 you might have thought that the ECB would have at least prepared for the possibility, so that if the governing council hit the panic button it would be ready to go. But that is not how the ECB works. It is at least consistent in always putting off until tomorrow what it should have done yesterday – actually it put it off for at least six years. The measures that were announced will take some considerable time to have an effect.

I have never understood why the governors of the central banks of Estonia, Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia and Slovakia and even France would go along with ECB decisions over the last several years which have so obviously been against their national interests.

It is also hard to see why Estonia, which joined the euro in 2011, and Latvia, which joined at the start of 2014, would want to join given the mess they were getting into.

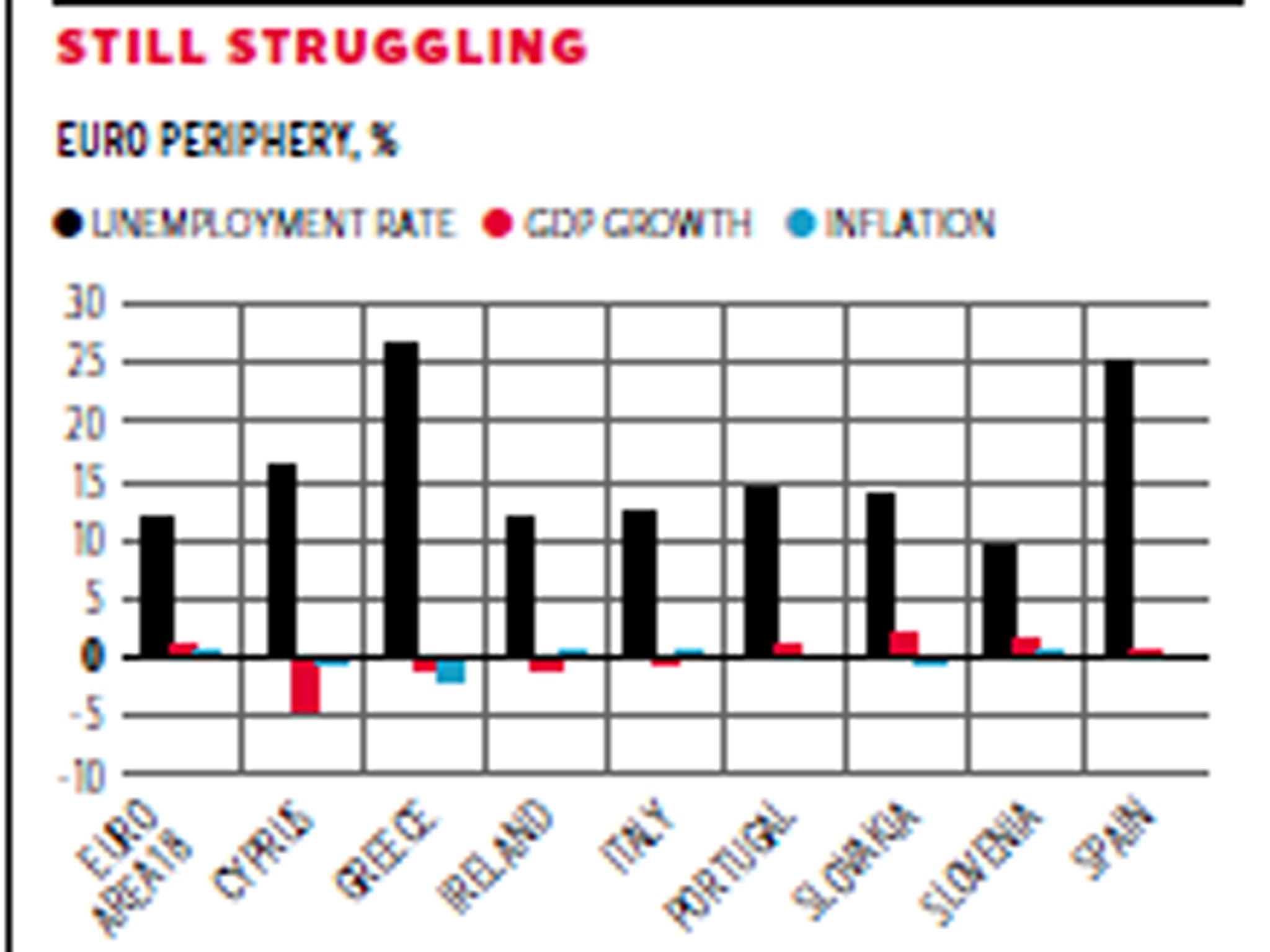

The chart illustrates the terrible situation all of these countries are in. It plots unemployment rate for eurozone periphery states in April 2014 (February 2014 for Greece) alongside the April inflation rate and finally GDP growth over the four quarters Q2 2013-Q1 2014. Data are taken from Eurostat.

I should once again note that, inexplicably, and just like Greece, the UK can only provide data for February 2014. It’s hard to know what is happening in the UK labour market when the data is so bad.

The chart shows the nature of the problem. The unweighted average of the unemployment rate across these countries, (and also Latvia, Estonia and France) is 14.6 per cent, with Greece and Spain over 25 per cent. The unweighted average is not unreasonable here as we can treat each country, big and small, as a separate data point, so that way the big country, France, doesn’t dominate.

The unweighted average of the inflation rate is 0.2 per cent and of GDP growth is 0.1 per cent. So these countries have high unemployment, no inflation and no growth. Five of the countries (Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Ireland and Italy) have had negative growth over the past year, while four are already experiencing deflation (Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Slovakia).

Plus the situation is likely to get worse on the inflation front because the individual country rates are from April 2014 when the euro area average was 0.7 per cent and we have a flash estimate for the euro area as a whole of 0.5 per cent in May. It may well be that the number of euro area countries in deflation will go up from the current four of Cyprus, Greece, Portugal and Slovakia.

The ECB’s projections for real GDP growth for 2014 have been revised downwards and the projection for 2015 has been revised upwards with real GDP projected to increase by 1.0 per cent in 2014, 1.7 per cent in 2015 and 1.8 per cent in 2016.

The ECB staff foresee annual inflation at 0.7 per cent in 2014, 1.1 per cent in 2015 and 1.4 per cent in 2016. In the last quarter of 2016, inflation is projected to be 1.5 per cent. In comparison with the March 2014 ECB staff macroeconomic projections, the projections for inflation for 2014, 2015 and 2016 have been revised downwards.

Both of these forecasts though may well prove overly optimistic, as they have been consistently.

Better late than never, but when you are this late things usually don’t get that much better.

Too little, too late.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments