The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

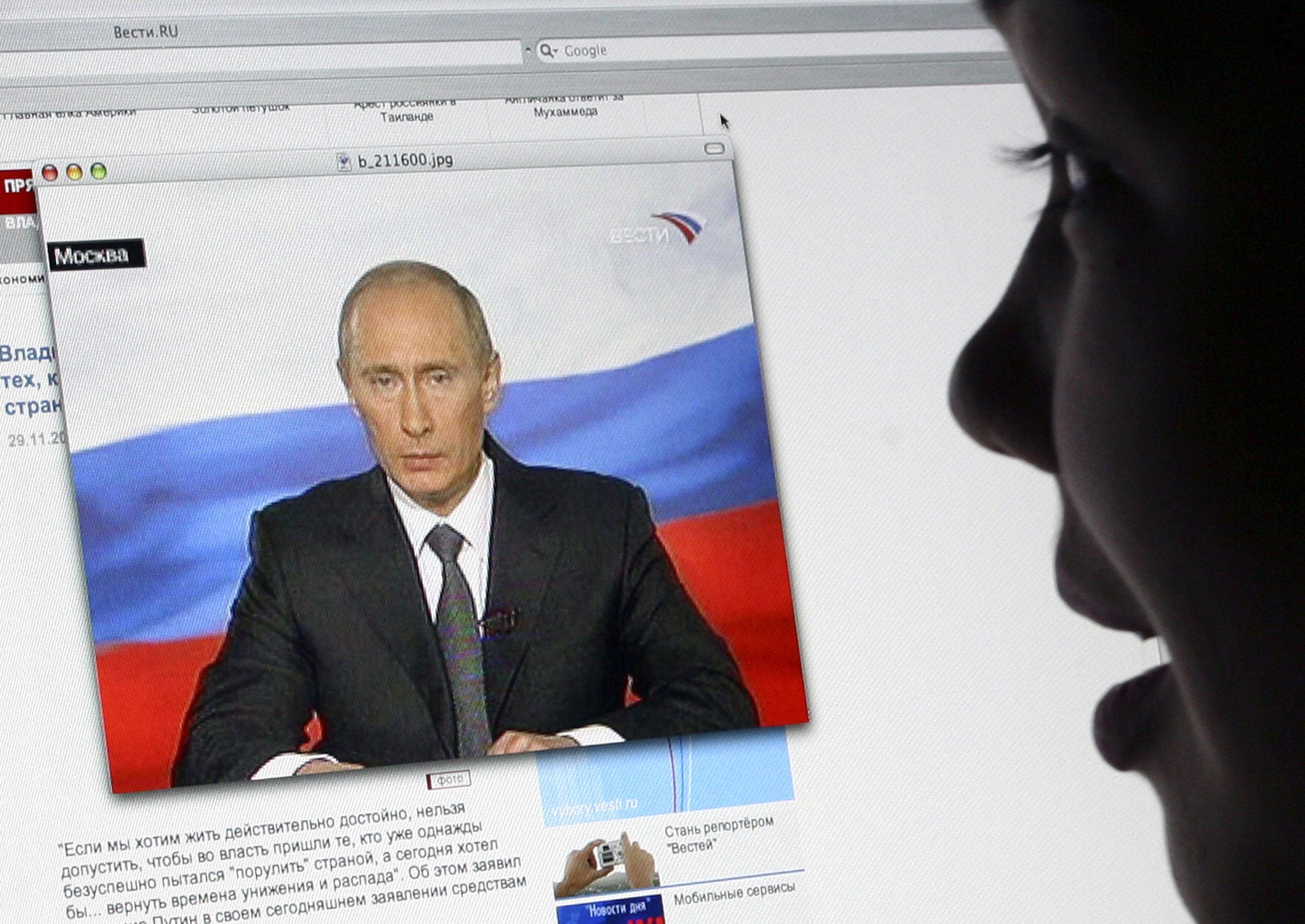

The internet was the last free zone in Russian society. Now Putin has it in his grasp

As a former secret agent, it frightens the Russian leader that information can be shared on such a scale

Vladimir Putin hates revolutions. In 1989, he was horrified when East Germans burned the Stasi headquarters in Dresden, where he worked as a young KGB agent. He took Russia’s 1991 revolutionary overthrow of the Soviet system as a personal betrayal. He scoffed at Georgia’s Rose Revolution in 2003, and derided Ukraine’s (failed) 2004 Orange Revolution. He loathed the crowds in Cairo, Tunis and Tripoli that formed the Arab Spring, and he continues to back his bandit client Assad in a bloody civil war against the Syrian revolution. And, most recently, when revolution came too close to home, he invaded Ukraine following the toppling of the Yanukovich regime.

The Russian president drew his own conclusion from all of these events: all talk of democracy leads to protests, and protests lead to revolution. The bottom line: Russia must end all talk of democracy.

Thus, when he became Russia’s leader back in 2000, Putin began the process of undermining democracy in Russia and stifling freedom of expression. First, he cleansed the Kremlin of opponents and ended political pluralism and installed his inner circle. This included old friends from his days as a KGB agent time working for the mayor of Saint Petersburg; they became rulers of Russia’s kleptocratic economy and enforcers of the Putinist system from which they profited.

Soon he attacked the media’s freedom. One by one, he shut down the liberal newspapers that had sprung up in the 1990s since the Perestroika reforms. In some cases, their editors and journalists were “kindly asked to leave”, in others, they simply disappeared. Having marginalised print media, Putin turned his attention to Russian television. Broadcasters that once carried lively debates were turned into stultifying Kremlin instruments. As state-controlled TV stations began to spout increasingly convoluted theories to demonstrate their loyalty to Putin, Russian propaganda entered the realm of the absurd – so much so that Soviet propagandists would hide behind their Putinist counterparts.

Once he cleared Russia’s politics, economy and media from undesirables, Putin turned to society itself. December 2011 witnessed the biggest demonstrations post-Soviet Moscow had ever seen. So Putin used the courts: Russia conducted dozens of political trials, many of them unreported. Today, with Russia in a de facto state of war, Putin’s societal re-engineering has intensified. The Kremlin now categorizes citizens into either “traitors” or “patriots”. It is able to do this by maintaining a monopoly on patriotism, Putin having hi-jacked the concept by presenting himself as the guardian of traditional Russian values.

But one combustible tool had so far eluded Putin’s grasp: the Internet. Until recently, Russians could only breathe freely online. The online world would offer alternative narratives to the propaganda Russians were spoon-fed on television and in print. Online, Russians entered another, freer world to the claustrophobic cage that Putin’s Russia had become.

Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t long before Putin declared war on the web. Today, Russia’s most famous blogger – Alexei Navalny – is under house arrest, and Pavel Durov, the founder of Vkontakte (Russia’s answer to Facebook) has been forced to flee the country. New laws require that foreign networks have their servers inside Russia, and that Russian bloggers with over 3,000 followers register with the state.

Putin never quite understood the Internet. Between 1985 and 1990, he was a KGB agent in East Germany, sending communiqués by telegraph and transporting messages in his shoes. His next stop was the Saint Petersburg mayoral office, where shady deals with gangster businessmen were sealed with the help of a fax machine. He was appointed as Russian president on New Year’s Eve 1999 – several years before the dawn of the social-media and smartphone era.

As a former secret agent, it frightens him that information can be liked and shared on such a scale. As the self-proclaimed protector of the “Russian world” (what Putin calls former Soviet lands), he dislikes Russians being so exposed to Western values. As the head of a kleptocratic economy, he feels threatened by Russians taking control of their own business needs. And, as an ultra-conservative, he is disgusted by the Internet’s liberalism.

Putin’s Internet illiteracy sets him apart from his Kremlin colleagues. Dmitry Medvedev, the puppet prime minister who kept Putin’s presidential seat warm between 2008 and 2012, has a reputation as a tech nerd who sought to create a Russian Sillicon Valley (the Skolkovo project). Ramzan Kadyrov, Putin’s loyal Chechen warlord, posts daily photos of his large family on Instagram. And Putin’s aggressive deputy prime minister, Dmitry Rogozin, is an avid Twitter user.

Yet the Russian president’s ignorance of the online world is clear for all to see. Putin dismissed the Internet as being “50 per cent porn”, claims he “never sent an email before” and, most recently, called the web a “CIA project”.

The Kremlin justifies its invasion of the Internet by alleging that it wants to protect Russians from America’s Intelligence services, enforcing its point of CIA aggression by parading Edward Snowden live on TV during Putin’s annual Q&A marathon. In reality, the Orwellian legislative document Russia drafted to combat the USA’s influence is only boosting the Kremlin’s own power to eavesdrop on its citizens.

Putin claims he wants the Internet to “serve Russian national interests”. In reality, his policies undermine Russian firms. Moments after Putin called the Internet a CIA project, the value of Yandex – Russia’s largest search engine – fell 5 per cent. Those Russians who leave Yandex will most probably go to Google. Surely Russia’s real national interests lie in supporting economic prosperity and social progress, not in defending Putin’s status quo.

Tragically, Pavel Durov has left Moscow. Yet he was everything Russia wanted – and needed: a young bright mind that could actually compete with the West using Russian products. And now, the only person in post-Soviet Russia that actually invented something is shopping for a new passport. Clearly, Russia has abandoned its dream of becoming a modern, functioning state in the name of Putin’s criminal regime and his mad imperial politics. There was nothing wrong with the small breathing space Russians enjoyed online – it was harmless to the Kremlin. Now, it is about to become much harder for Russians to speak freely.

Authoritarian regimes watch what you say; dictatorships watch what you think. Is Russia about to take that giant step backwards? If so, Putin could be headed for revolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments