The joys of boredom!

Modern life is so full of distractions, there's a risk we never get beyond the surface. Andrew Martin admits a bit of tedium can put the good things into proportion

Should readers be at a loose end today, they might like to know that a Boring Conference is being held in east London. Throughout the day, talks will be given on subjects including pylons, double yellow lines, self-service checkouts and shopfronts.

The conference is organised by James Ward, who blogs about stationery and other boring things. He first held a Boring Conference in 2010, on learning that an event called the Interesting Conference had been cancelled. He simply booked the same speakers whose subjects were "things that, on the surface, would appear to be boring but aren't" and relabelled the event.

If you ask me, a lot of subjects come into that category. I speak as someone who in recent years has written articles on such boring/interesting topics as the town of Cromer, the George Formby Appreciation Society, abnormal loads (that is, the carriage by road of loads that take up more than one lane of the motorway) and the roundabouts of Milton Keynes. The more you know about something, the more interesting it becomes, and there's a great pleasure to be had in seeing someone not going to sleep as one explains the history of crazy golf, or how mind-reading is done (both subjects on which I can and do give long lectures).

A friend of mine regularly took his early-teenage son to classical music concerts, protracted church services, exhibitions of obscure art. "But, Dad, it's boring!" the boy would say. "That," his father sternly replied, "is the whole point." He thought it necessary for his son to develop a high boredom threshold such as is necessary in the early stages of learning to play the violin or speak Mandarin. He wanted to wean the boy off overstimulation.

Personally, I have a high boredom threshold. It's an essential requirement in someone who reads a lot about transport, and I am in no way deterred by titles such as Tank Engines, Classes L1 to N19 or Leyland Bus: The Twilight Years. Heidegger believed that the essence of boredom lay in waiting for a train. Well, I've just come back from a three-day mini-break spent in a station waiting room on a closed-down railway. It was at Alton in Staffordshire, and I loved the silence, the ticking clock, the waxing and waning of the fire in the stove.

I accept that boredom is not necessarily a good thing. A bore is someone who doesn't care whether you're interested in what he's droning on about, but this man must be distinguished from the innocent enthusiast. I knew one of those at university: a lovely man who would give enumerated monologues on almost anything, honestly believing you were interested in why the novels of Sir Walter Scott were well worth tackling or why Richard III wasn't such a bad chap really. It was said that he once began a sentence, "Thirteenthly ...".

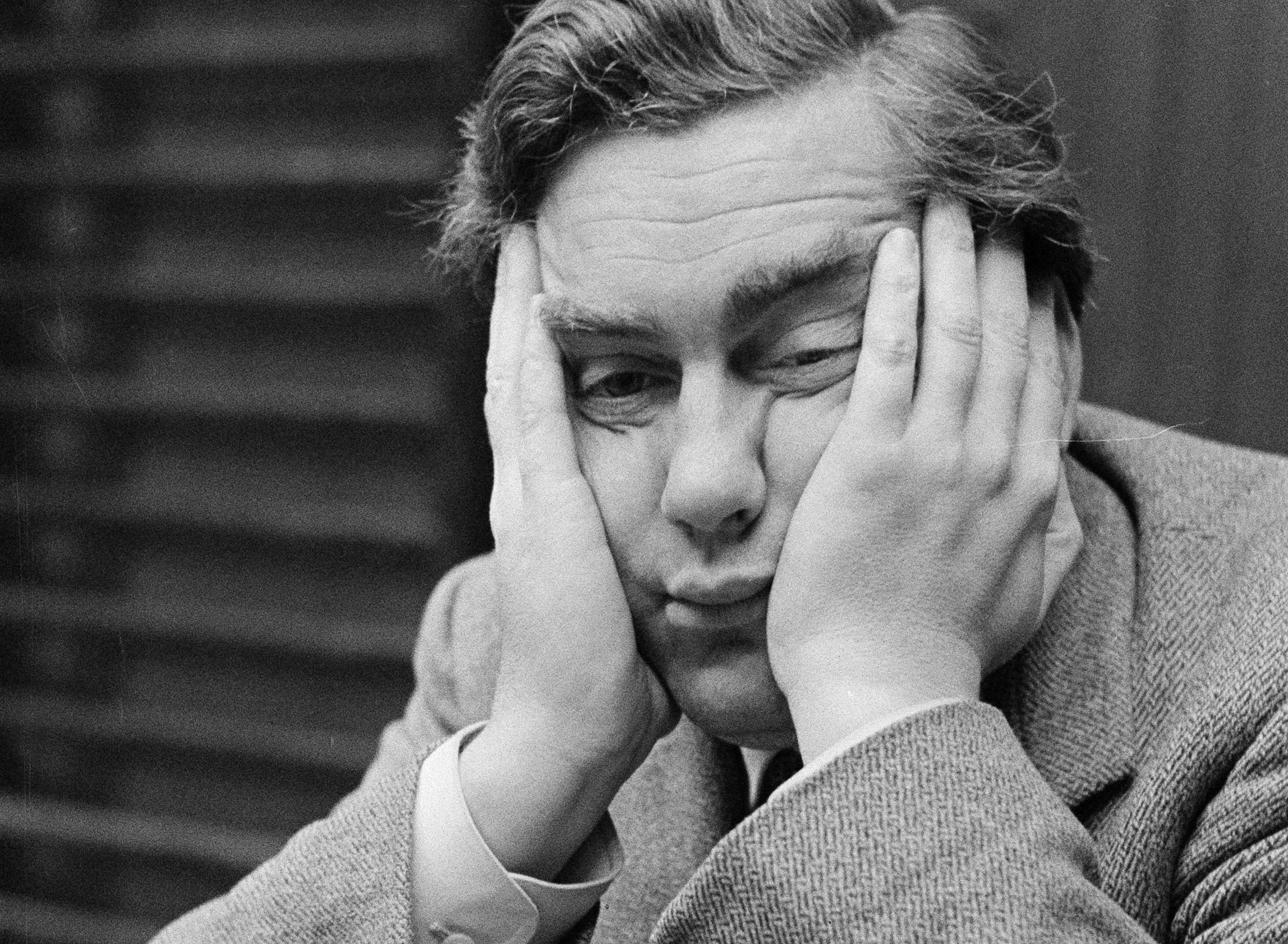

Another innocent bore is Eric Olthwaite, a character portrayed by Michael Palin in his brilliant Ripping Yarns series. Olthwaite is so boring that his father, a coal miner, pretends to be French so he doesn't have to speak to him. Eric has two interests in life: first, indices of rainfall or, as he calls it, "precipitation", and, second, shovels. Trying to chat up a girl, his opening gambit is, "Guess who's got a new shovel, then?"

A different sort of forgivable bore is the person who admits he's boring, offering the information he has to impart in a take-it-or-leave-it manner. It is said that one of the Dukes of Devonshire yawned hugely during his own maiden speech in Parliament because he was just "so damned dull".

Boredom is nostalgic for me: it reminds me of my 1970s childhood, when not so much was going on. In fact, the dominant social theme of my lifetime is the displacement of the ordinary sort of boredom, arising from having insufficient distraction, by the boredom that comes from having far too much distraction but with no real interest in any of it.

When I was a boy, football was confined to Saturday afternoon. Everything closed on Sunday, and most things closed at 1pm on Wednesday. If someone wanted to send me a written communication, they wrote a letter and posted it, but they usually didn't bother. If they rang up and I was in, I would speak to them. If they rang up and I was out, my sister would write down a message on a bit of paper, which would then get lost. I admit there were moments in the depths of a rainy Sunday when my day would be like the famous Hancock's Half Hour episode, punctuated by yawns, melodramatic sighs and family recrimination.

I must have been frequently bored as boy because my dad had all these supposed panaceas, most of them complete non-starters: "Do some colouring-in"; "Go for a walk"; "There are plenty of jobs around the house that need doing".

Then I would take matters into my own hands. The effort of will needed to escape the quicksand of boredom resulted in dramatic and worthwhile endeavours. I would write a film script, or throw out half my possessions, or run five miles. A friend who became a vicar used to say, "Has it ever occurred to you that God deliberately leaves Sunday blank, so you have to think?", and I would agree there was something in that.

I do not believe that when I was a child I ever stood in a post office queue thinking, "I wish there were a television screen in front of me, so I could learn about all the latest special offers while I wait." I don't think I aspired to be able to "watch movies on the go". Did I want to be part of an electronic network that would enable me to access at the touch of a button much of the world's music and literature? Not especially.

In his book Boredom, Peter Toohey writes, "Boredom is connected to surfeit", hence the expression "fed up". This strain of boredom is connected in my mind to what Toohey calls "melancholy" or "existential boredom", which "is often said to be the great characteriser of our age". It is related to the Marxian concept of alienation, the sense of being merely a pawn in a capitalistic chess game, because, let's face it, everyone trying to grab our attention is also trying to get money off us.

When, as a boy, I experienced traditional boredom, I blamed myself. Faced with existential boredom, I blame society. No doubt it's churlish of me not to want a text alert every time my football team scores, and I suppose there are some people out there who love the idea of "rolling news". But, surely, if more entertainment on tap is the answer, then the question must be wrong. Instead of fleeing boredom, why not turn round and embrace it?

The Boring Conference is at York Hall, 5-15 Old Ford Road, E2 9PJ. Tickets, £20; tel: 020 7638 8891

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks