Turning a blind eye to moments of death is a strange, modern taboo

Whatever your beliefs, we must recognise the dead left their empty shell and now dwell elsewhere

Earlier this month, the BBC’s Newsnight programme broadcast at length and in detail the lynching of a young woman by more than 100 enraged men who beat, kicked, ran over, stoned and burnt their victim while police stood by. It was right to do so. True, Newsnight suppressed the mob’s final assault on 27-year-old Farkhunda Malikzada, a student of Islamic law falsely accused in Kabul of burning a Koran. Still, the camera lingered unbearably longer than it usually does. Made with tact and courage by Zarghuna Kargar, the film put the atrocity in context, interviewed both Farkhunda’s family and her persecutors, and explained why murderous misogyny remains the norm in a supposedly liberated nation. Anyone who still believes that Western armed force in Afghanistan has achieved even a tiny fraction of its stated aims should view the report.

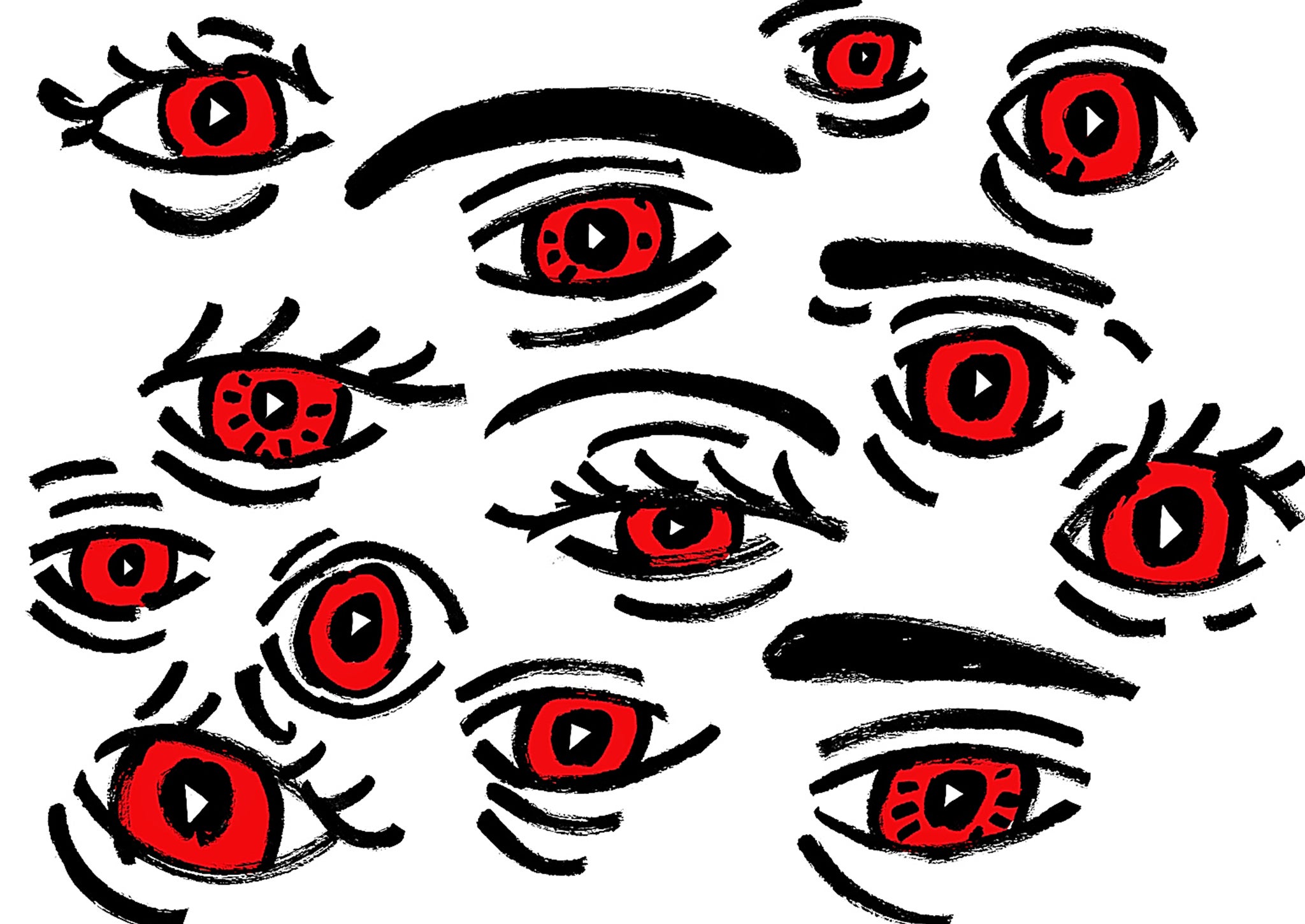

Images, even images of death, have no single meaning in themselves. The old adage is exactly the reverse of true: a word – or at least the right word at the right time – is now worth a thousand pictures. Zarghuna Kargar gave us that. Thread the visual enormity into a narrative that makes some human, and humane, sense of it, and even the most “graphic” frame – to enlist the newscaster’s favourite weasel adjective – may justify its place. Online, that seldom happens. When, this week, TV reporter Vester Flanagan shot his two former colleagues live on air in Virginia and then uploaded the film of his crime, the “autoplay” function on Facebook and Twitter accounts went on circulating this record of a double murder even after social-media bosses pulled the plug. Ghouls, psychopaths and prurient teens aside, many users became involuntary witnesses of violent death.

From the chamber of desert horrors digitally edited by Isis to raw footage of shoot-outs and aircraft crashes, we all know in theory if not practice that the net delivers a 24/7 “atrocity exhibition”. That was the title chosen in 1970 by the prophet of new-media delirium, J G Ballard, for a batch of stories inspired by the endlessly recycled film of J F Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. Even in the grainy 8mm Kodachrome stock of the Sixties, Ballard saw what lay in store for us.

It’s easy enough to mount a moral grassy knoll and censure the voyeurs, thrill-seekers or downright maniacs who go online to gawp at Isis torture videos, murder recordings or the aftermath of disasters. However, might our media conventions of “decency” and “discretion” also enshrine lapses of taste, even blatant cruelty? Consider the Shoreham air show crash. We see on primetime screens the aircraft’s doomed descent and the resulting fireball. Somehow, the moments of impact – the moments of death – remain utterly taboo. Why?

As death has retreated from life in the affluent world, no longer an everyday companion but a sanitised medical mystery, so the prohibition over showing it in fact rather than fiction has deepened. The vigils and wakes that sent the departed on their journey in consoling rituals have by and large given way to the quietly drawn curtains on the hushed ward. Most people in Britain still die in hospital, although it turns out that the number who quit this life in their “usual place of residence” is actually on the rise again: up from 38 to 44 per cent between 2008 and 2012, according to Public Health England. Remember, though, that the usual residence will often be a “home” and not their home.

Fewer of us now view the dead, even the dead who mean the most to us. We should. Because their presence proves their absence. Whatever your beliefs, you must recognise that they have left that empty shell and now dwell elsewhere – even if only in the memories you keep of them. Yet the visual euphemisms of the polite media – with their command to “Look away now”, having titillated us up to the brink of slaughter – also connive in this new mystification of death.

One of the most striking stories to emerge from the Shoreham crash was that of Terry Hallard. He saw the aeroplane fall, almost 63 years after – as a boy of 12 – he had witnessed the Farnborough air show crash. In September 1952, 29 spectators and two crew died when a prototype De Havilland 110 fighter broke up in mid-air and its burning engine crashed into the crowd. In Empire of the Clouds, his history of post-war British aviation, James Hamilton-Paterson evokes the near-incredible stoicism of the Farnborough scene. “An extraordinary silence” followed the impact. The wife of pilot John Derry turned to a colleague and asked, “There’s no hope, is there?” “No, none.” The show went on even as ambulances arrived and medics tended hideous wounds.

Almost immediately, test pilot Neville Duke flew a Hawker Hunter – the same type, now a vintage curiosity, that crashed at Shoreham – through the sound barrier. Seven years after the end of the Second World War, that choice “was perhaps more comprehensible to those who could remember active service, and how in war there was seldom time to grieve”. In the crowd, many who had not fought themselves would have endured the Blitz. The next day, Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent Duke a message of support: “Accept my salute.” No one dreamed of suing the manufacturers or the organisers. As Hamilton-Paterson writes, “Many things about Britain some 60 years ago were strange, even quite brutal.”

Bitter experience of loss had cemented millions of stiff upper lips in place. Now we circle obsessively around the circumstances of death but recoil from its sight. Yet the serious broadcaster’s rule – show the preludes, the outcomes, but not the fatal event itself – betrays a queasy kind of fetishism. The bodies of the dead merit sacred seclusion but the anguish of the living, however extreme, is fair public game. Cut from the corpse, focus instead on the fear and grief of victims, survivors or relations, and you stay safely within our bizarre laws. This week, a newspaper that likes to lecture public broadcasters about ethics displayed on its front page the face of the young journalist in Virginia as Flanagan took aim at her. That last look of shock and terror presumably violated no guidelines. There was no body and no blood. I still found it obscene.

In the past, representations of the dying and the dead served many purposes. For medieval Europeans, no image merited more reverence that the horrifically tortured Christ on the cross, dying his slow, slave’s death. To late-Gothic artists, the worse the suffering, the holier the image. In the Crucifixion altarpieces of Matthias Grünewald, the scourged, ravaged, purulent, moribund body inspires devotion to a Jesus who (in the words of novelist J K Huysmans) dies “like a thief, a dog… He had sunk himself to the deepest depth of fallen humanity”. Some viewers may find these images distressing? That was the whole point.

As faith withdrew to the margins of European life, death masks cast in plaster or wax preserved the face of genius, fame and power. Widely reproduced, the visage with which a Cromwell, a Voltaire or a Napoleon departed became as much a part of their posthumous glory as any studio portrait. Whether serene or struggling, the face of death in a great one brought honour and not shame.

Even the advent of photography failed to banish pictures of the dead from polite society. During the Victorian age, advances in the technology of print and image far outpaced progress in medicine. The result was the fashion for post-mortem photography, with depictions of dead children – often garlanded with flowers – treasured by bereaved families or made into calling cards. Grieving parents saw nothing macabre in the custom. Only hindsight finds it morbid.

Today, media codes dictate that invisibility alone can confer respect. To reveal is to desecrate. The meaning of mortality in photographs, however, will change from viewer to viewer. After Che Guevara’s death in Bolivia in 1967, the critic John Berger published an essay that compared this image – transmitted to prove the guerrilla leader had really been killed – both to Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Professor Tulp and Andrea Mantegna’s painting of the dead Christ. Both Rembrandt and the CIA-backed Bolivian army, Berger writes, wanted to “make an example of the dead”. However, the dead Che was seen around the world not as proof of “the absurdity of revolution” but an emblem of its dignity and value.

The Isis curators of execution-porn sites need no further curses here. We know what they do and why they do it. Likewise the mercenary ringmasters of freak-show video aggregators such as LiveLeak (trending on the site today: “teenager in agony after being shot in the head”). Think twice, though, before assuming that the closed eyes and the covered lens always represent the better way. In 1955, the 14-year-old Emmett Till was tortured and killed in Mississippi after he had allegedly flirted with a white woman. Before the funeral, in Chicago, his mother Mamie insisted on an open coffin. About 50,000 saw the mutilated corpse; African American magazines carried the image to millions more. Emmett’s ruined face became an icon of the growing civil rights movement. As Mamie Till said, “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments