The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

We need a 21st century Voltaire Test to fight the growing power of censorship around the world

Religious groups everywhere - and particularly Muslim ones - are demanding limits to free expression which are unacceptable, dangerous and counter-productive

In the context of the Pussy Riot trial in Moscow, the anti-Islam film Innocence of Muslims, the cartoons of the Prophet Mohommed in the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, and the pulling of the repeat showing of Islam: the Untold Story by Channel 4, there is again much discussion and debate about freedom of expression and its limitations.

The Moscow court made its position clear by imprisoning the three women band members, a verdict supported by the offended parties, Vladimir Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church; though one member of the band has won her appeal. In regard to the anti-Islam film, those offended by and protesting against it (Salafists in the main) demand nothing less that the death penalty for the makers of the film – a demand backed by and incentivised with a bounty of $100,000 by a politician in a country where the blasphemy law reigns supreme, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

The US government as represented by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has, on the one hand, spoken firmly in favour of Pussy Riot but, on the other, has forcefully condemned the anti-Islam film. Her department's spokeswoman Victoria Nuland urged the 'Russian authorities to review this case and ensure that the right to freedom of expression is upheld'.

Hand-wringing

One presumes that Clinton’s dichotomy of opinion on freedom of expression would also be shared by many other western leaders, with the implied assumption that in the game of who is offended most, fanatical and violent adherents of Islam take priority over the relatively unassuming members of the Russian Orthodox Church. One shudders to think what would happen to the equivalent of a Pussy Riot performing in a mosque in a Muslim country but somehow it is doubtful that such a band would receive anything like the same level of support from western leaders.

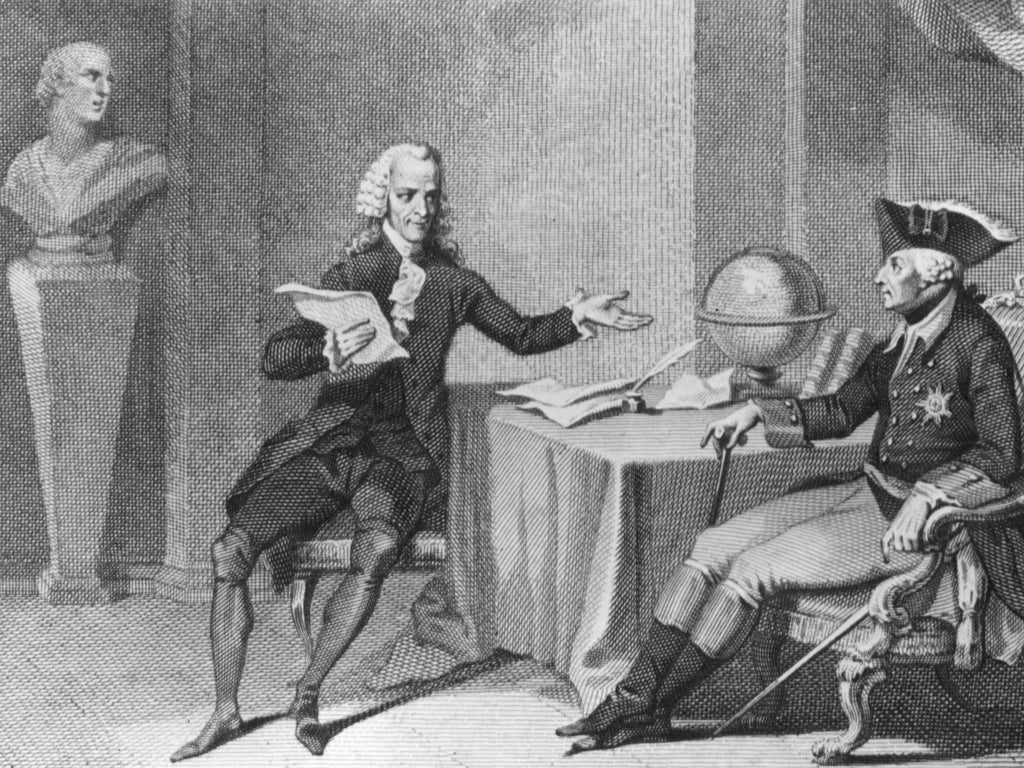

Whilst all this hand-wringing is going on regarding religious sensibilities, it would be helpful to remember the famous remark attributed to Voltaire – let us call it the ‘Voltaire Test’: ‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it’. This should be the true test of freedom of expression, not the fake one whereby ‘you are free to say what you will unless large numbers disapprove and threaten or resort to violence’.

To the oft-quoted quip ‘freedom of expression does not give one the right to shout “fire” in a cinema hall’, the rejoinder is simply no it does not if there is no fire. But this is surely a curtailment of freedom of expression? Indeed it is but untrammelled free speech is not being advocated; on the contrary it is curtailed where there is a clear and present danger of injury.

Given that shouting ‘fire’ in a cinema risks invoking panic, a crush, injury, and death, it is proscribed in the absence of a fire. Equally, where freedom of expression involves threats of violence, it is also proscribed. However, none of these limiting factors apply to the demands incessantly being made by religious groups. But what about the argument that freedom of expression must not be too extreme as to cause genuine offence?

Mr Bean's example

This was John Stuart Mill’s riposte in On Liberty to this limitation: ‘Strange it is that men should admit the argument for free discussion, but object to their being ‘pushed to an extreme’; not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case’.

Back in 1989, after Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie, many soi disant progressives abysmally failed the Voltaire Test and, de facto, joined the ranks of those for whom freedom of expression is an abomination. One of the latter group, Inayat Bungawala, a young man then but now a prominent Islamic leader in Britain, has, to his credit, become embarrassed by his youthful joining up with many of his book-burning co-religionists – which is not to say he will pass the Voltaire Test.

Let us, however, hope that the ‘progressives’ who joined Bungawala in advocating censorship are likewise also embarrassed by their lack of principle and cowardice 23 years ago and will now pass the Voltaire Test. Let us further hope that they robustly take up the cudgel against the pressure being mounted by the 56 member countries of the Organization of the Islam Conference to bring about a blasphemy law writ large – one that will make it a criminal offence to disparage religion, above all Islam – which is tantamount to the overturning of the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

Perhaps they can take the lead from the comic Rowan Atkinson who, in his intervention on the religious hatred bill in 2004, raised the very serious clarion call: ‘The freedom to criticise ideas, any ideas - even if they are sincerely held beliefs - is one of the fundamental freedoms of society ... the right to offend is far more important than any right not to be offended’. He would surely pass the Voltaire Test.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments