World leaders in their 30s? Change is in the air and we’d better get used to it

A new generation is shaking up the way politics is conducted

With the recent victory of an 88 year-old in Tunisia’s first democratic presidential election, an 89 year-old still in harness as President of Italy, and, of course, our own Queen, at 88, showing no signs of giving up her throne – despite a flurry of social media speculation - you might well conclude that this was the age of the gerontocrats.

Look more closely around Europe over the past year, however, and quite a different trend emerges. In mainstream politics, youth is busting out all over.

Let’s take a benchmark of 40 or thereabouts. Italy’s prime minister, Matteo Renzi, is 39; he was swept to the leadership of his centre-left party with almost 70 per cent of votes. Just before Christmas he steered his tax-cutting budget through Parliament against the odds. Striking a tone of efficient professionalism, he is about as far from the ageing seediness of Silvio Berlusconi as it is possible to be.

Pedro Sanchez, the new leader of Spain’s opposition Socialists – who may well come to power in elections this coming year – is a 42 year-old economist who bounded on to the political scene pretty much out of nowhere. The mayor of Kiev, who decided against standing for president this year, is the former boxer, Vitali Klitschko, now 43. The prime minister of the Baltic state of Estonia is a 34-year old, Taavi Rõivas.

Nor have Germany’s staid Christian Democrats (Angela Merkel’s party) been exempt. A 34-year old, Jens Spahn, has just made – sometimes critical headlines – by putting himself forward for election to the party’s presidium. In the event, he received two-thirds of the second round vote and is now a member of the party’s seven-member day-to-day leadership.

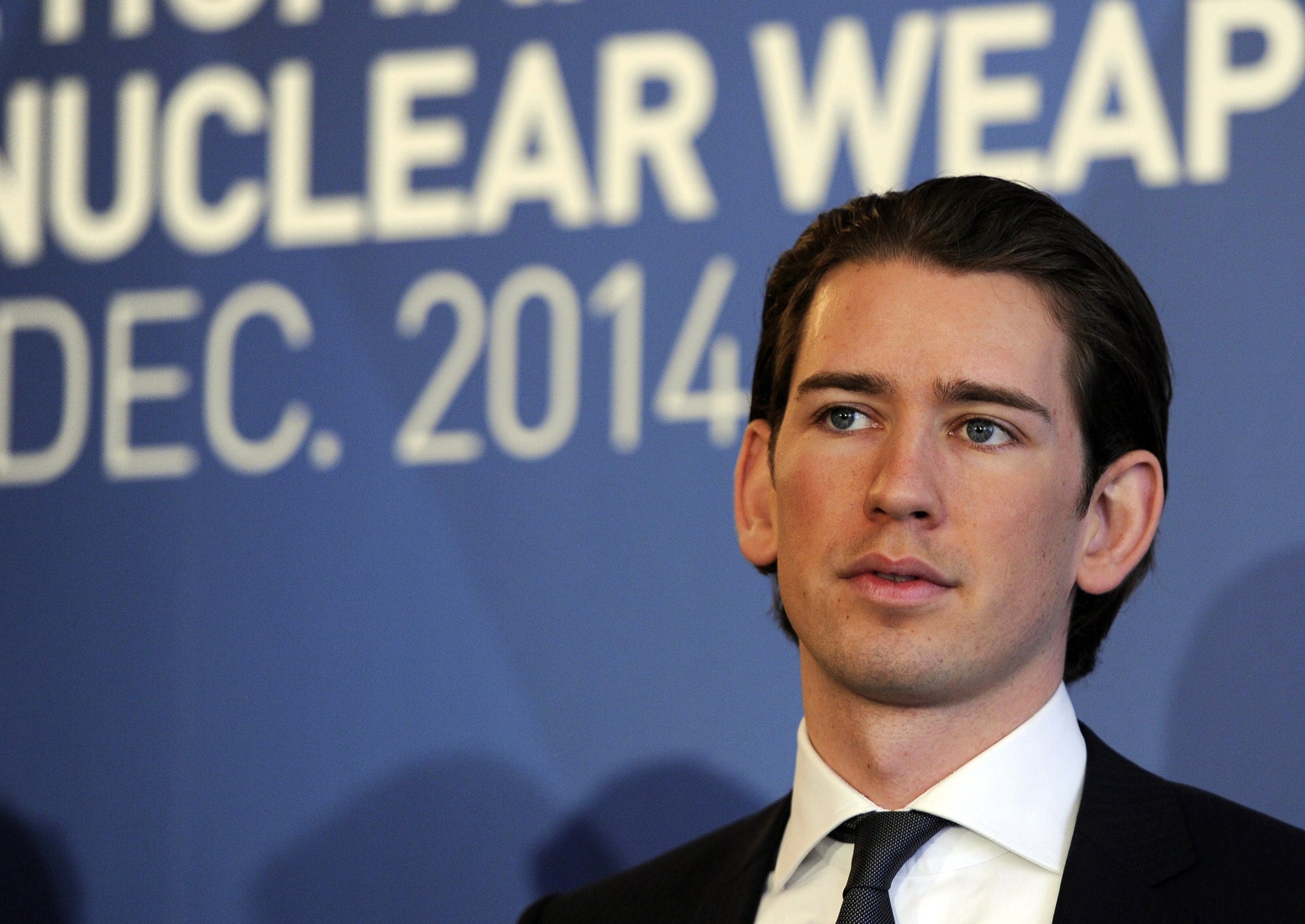

But it is Austria’s foreign minister, Sebastian Kurz, now 28, who takes the laurels in the political youth stakes. Kurz was promoted after three years in which he made an unlikely success of being integration minister, a portfolio he insisted on retaining in his new position. You might reasonably be sceptical about the capability of one so young, but I’ve seen him in action and was seriously impressed. He is Austria’s youngest government minister since the foundation of the republic and the youngest foreign minister in the EU.

What is striking about all these politicians is that they are not maverick outsiders. They have not founded insurgent parties, such as the Pirates, who made their mark a few years ago, thanks largely to social media. Nor are they part of any right-wing populist upsurge. They are working through the political establishment and setting out to change things from inside.

You could argue, perhaps, that the UK has been a bit ahead of the curve here. Remember how young Tony Blair looked when he became prime minister in 1997, at 43, or the Cameron-Clegg double act - compared to a civil partnership ceremony! – after the election of 2010. And George Osborne, forget it not, was still in his 30s when he became Chancellor the same year.

Think, too, of the engagement of young voters in the Scottish referendum - and not just because the voting age was reduced to 16, but because there was a real sense that the country’s future was at stake. The new SNP First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, has a long political career behind her, but is still only 44.

There are dangers in being propelled to a top job with little experience. Young men (still mostly men, alas) can also be in too much of a hurry. Germany’s great white political hope, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, had to resign as defence minister in 2011, when he was 40, after admitting that he had contracted out the work on his doctoral thesis.

But inexperience also carries advantages, especially when technology and communications move as fast as they do today. A young politician may be less afraid of breaking moulds, more open to new ways of doing things, less beholden to patronage built up over the years, and more in tune with the language and concerns of more voters. The old ways – as ministers who have tussled with Whitehall’s more hidebound civil servants – are not always or necessarily the best.

Nor, perhaps, are the policies. As the UK enters this election year, there is already much agonising in political circles about how to engage voters, including young voters, with envious glances cast back at the Scottish referendum. There are those lobbying to reduce the voting age; others are calling for updated procedures, such as e-voting. And the Demos think-tank releases a report next week looking, among other things, at policies. A sneak preview suggests that the priorities of the young diverge not just on obvious subjects, such as housing or pensions. Its polling also found that young voters were less concerned about immigration than they were about privacy online, and would like more younger MPs with closer local ties.

Politicians should sit up and take notice. If they want a wider spread of voters, they perhaps need more imaginative policies, and some new political voices to reflect them. For if you look around Europe today, you will notice not just how a new crop of young politicians is emerging, but how set in their ways and bereft of solutions even the most accomplished, such as Angela Merkel, are starting to look.

A heroine needlessly adapted for our times

Speaking of bright young things, an early major release in the New Year will be the film of Vera Brittain’s 1933 best-seller, Testament of Youth, starring the Swedish actress, Alicia Vikander, in the title role. Brittain, as those of my vintage will doubtless know, not only went up to Oxford as one of very few women admitted in those years and not only became a doughty campaigner for pacifism after losing her fiancé in the war and serving as a volunteer a nurse’; she also had a direct connection to the present, as she was Shirley (now Baroness) Williams’ mother.

Those of my vintage may also recall that Testament of Youth had an earlier outing on screen, in BBC Television’s 1979 serialisation. My memories of that version may not be exact, but they are fond, and the contrast is not to the new film’s advantage. Forgive me if memory deceives, but the earlier Vera seemed less preoccupied with herself and more a part of the wider context. In the new film there is a “star” quality to the acting, and a knowingness to the production, that was mercifully absent from the TV serial. The feminism seems somehow cheapened, and the depiction of war both cruder and more consciously calculated to shock.

Perhaps that is all part of belonging to a more media-savvy, celebrity-orientated age. But take one look at Cheryl Campbell on the cover of the earlier BBC version and Vikander on the posters for the film and you may see what I mean. Restraint can be more eloquent and evocative than “significance” rammed into your face.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks