You don't have to be poor to go to Poundland

The proletarianisation of many professions means the abyss lurks not far beneath even fashionable feet

As it slices through north-west London along the route of the Romans’ Watling Street, Kilburn High Road has a good claim to be the hub of the galaxy. Don’t just take my word for it. The director Michael Winterbottom made a searing docudrama movie called In This World. It followed the perilous path of two Afghan refugee kids from a camp in Pakistan towards their longed-for destination in the West. That was, to be precise, Kilburn High Road.

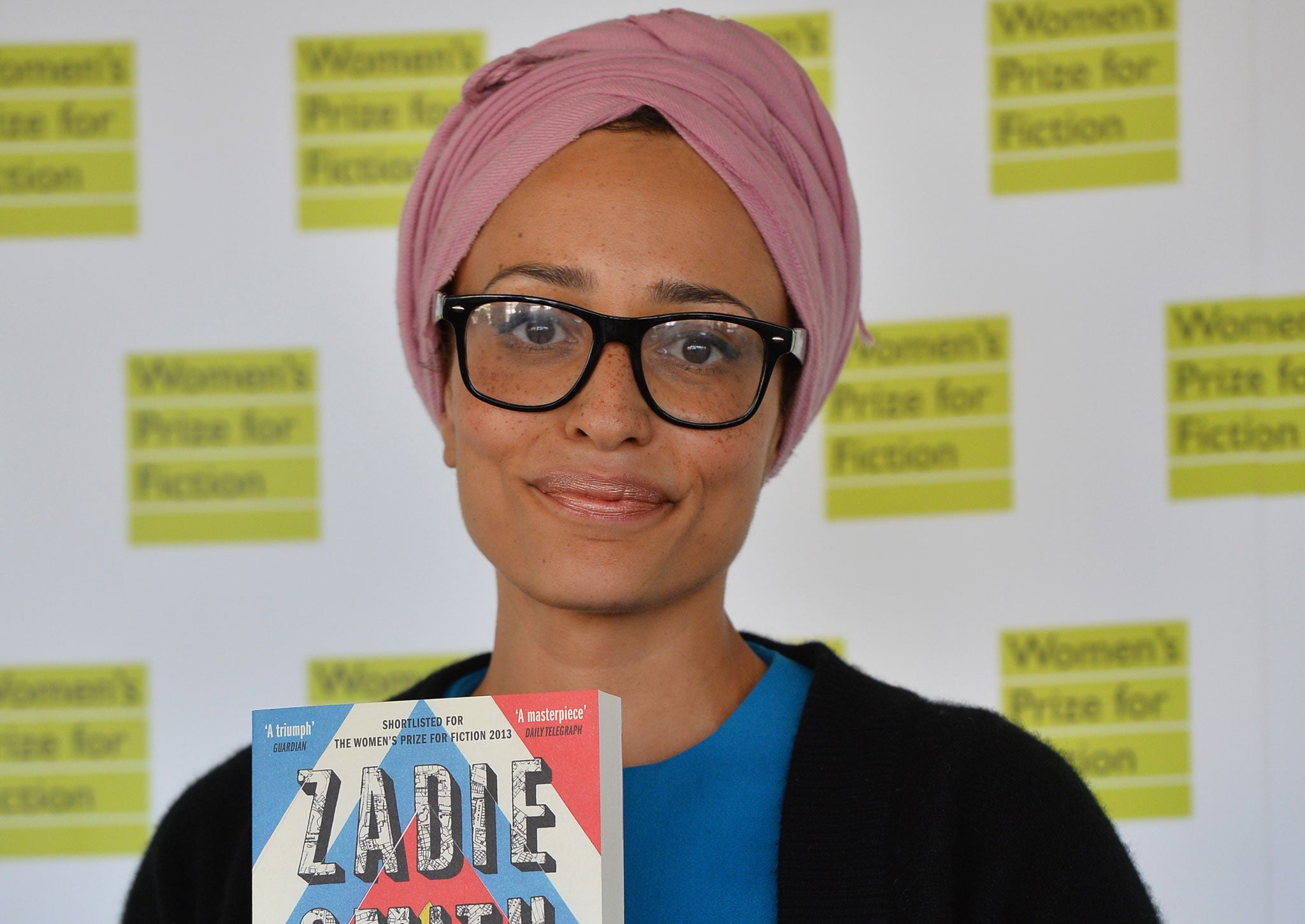

In the novel NW by local girl Zadie Smith, one character looks askance at the Tube map and mentally corrects it: “The centre is not ‘Oxford Circus’ but the bright lights of Kilburn High Road.” After a virtuoso evocation of the multicultural hubbub that makes the street a sort of global souk, Smith edges south almost into Maida Vale and proclaims, to point up her neighbourhood’s lurching clashes and collisions: “Here is the Islamic Centre of England, opposite the Queens Arms.”

Ah, but the reality trumps any fiction. At the Queens Arms itself, an Albanian-origin refugee from Kosovo called Besnik Sahatciu took over as guv’nor. He had a daughter who, thanks to her startling platinum glamour and turbo-charged pop voice, has grown up to become one of the best-known young women in the world. Her professional name is Rita Ora.

The old Roman arrow of Kilburn High Road flies across almost every outcrop and declivity in this fast-changing cultural landscape. All retail – all London – life is here. The billboard outside the site of a new-build apartment block actually quotes, in huge letters, Zadie Smith herself: “It’s not perfect – where in London will you find perfection? – but it’s alive.” I write this with feet stoutly shod in budget lace-ups snapped up from the Clark’s Factory Shop (highly recommended). As it moves between familiar chain giants such as Primark, M&S Simply Food, Iceland, Argos or Aldi and the quirkier local emporia, the High Road layers and shuffles the retail – and therefore social – history of its city and country. Smith celebrates its jolting hubbub in her urban rap or rhapsody: “Unlock your (stolen) phone, buy a battery pack, a lighter pack, a perfume pack, sunglasses, three for a fiver, a life-size porcelain tiger, gold taps. Casino! … TV cable, computer cable, audiovisual cables, I give you good price, good price. Leaflets, call abroad 4 less, learn English, eyebrows wax, Falun Gong, have you accepted Jesus as your personal call plan? Everybody loves fried chicken. Everybody. Bank of Iraq, Bank of Egypt, Bank of Libya… Bearing no relation to the debates in the papers, in Parliament.”

Well, sometimes the word on the Kilburn street does percolate up to reach the ears of opinion-formers. This week, people in power beyond the usual ranks of economic analysts have noticed the inexorable rise of discount retail. Painfully squeezed between the upmarket fare of Waitrose and the high-volume, low-cost offer of the German heavyweights Aldi and Lidl, the supermarket group Morrisons has announced a £176m pre-tax loss. Its emergency rescue package will involve £1bn in price cuts on everyday items. At Morrisons, the answer to the hoary challenge flung by interviewers at politicians – “What is the price of a pint of milk” – has fallen to “42p” (if you buy a two-pint carton). Although Aldi and Lidl together still command a market share of 7.3 per cent (compared with 28.7 per cent for Tesco), all the momentum in openings and growth lies with the most aggressive discounters.

Meanwhile, the fixed-price army of Poundland will storm the London stock exchange on Monday. Its flotation values the chain at £750m. Only four years ago, the private equity outfit Warburg Pincus paid only £200m for the store that occupied many a shopping parade void left by the defunct Woolworths. With Jane Asher as its marketing face for an own-brand range of cookware, Poundland has responded cannily to the swifter consumer traffic between both ends of the market. After decades of clustering around a bourgeois mean, we now almost expect to find the châtelaine frolicking in the bargain basement.

Kilburn High Road boasts two Poundlands within 300m of each other. One of these temples of thrift lies sandwiched, as in some Victorian morality tale, between payday lender The Money Shop and The Coopers Arms. Inside, I stock up on branded toiletries at a price to make Boots very sick indeed and notice, as usual, the signs of agile marketing: a display of £1 Mothers’ Day gifts, from chocolates to kitchenware. I want to leave a warning note for unwary kids: the Guylian pralines, certainly; the decorated oven gloves, no, no, no.

This polarisation of the high-street scene does not bring with it a new shopping apartheid that directs poor consumers to one door and the well-off to another. On Kilburn High Road, refugees or other precarious migrants may line up at the budget tills with the owners of the £2m homes in leafy avenues nearby. The street’s mammoth Aldi opened just a year ago. Even quite early in the morning, queues to pay already snake around the shop. Here 10 fish fingers cost £1.19 – but then so does a packet of fresh asparagus. Beyond the knocked-down staples in bulk, respectable champagne will set you back £12.99; balsamic vinegar, just 99p. Like Aldi and Lidl, Poundland reports that more than 20 per cent of its customers now come from the AB brackets. Penny-pinching frugality has become for some not so much a necessity as a sport and a fashion. Like so many Marie Antoinettes, playing at shepherdess in the grounds of Versailles, the affluent have more chances than ever to mimic the habits of austerity.

This may not always be a narcissistic stunt. In the UK, we now negotiate a marketplace both cheaper and dearer than ever before. Thanks to globalised economies of scale, I can clothe myself perfectly decently at the Kilburn branch of Primark for £30 or £40. As for the social cost of dirt-cheap threads to growers and sewers overseas, Western consciences have proved no match for bone-deep discounts. Protests outside Primark stores after the garment factory collapse in Bangladesh last April (which killed more than 1,100) lasted just a few days – although, to be fair, the group has since done more than most big rag-traders both to compensate bereaved families in Dhaka and to scrutinise its supply chain.

Yet if I wished to purchase even the pokiest, tiniest flat above a shop on the High Road, I would see no change from £400,000. On Brondesbury Road, which leads off the main drag, one five-bedroomed house has come to market at £3,950,000. Sky high and rock bottom now co-exist. They don’t make large, handsome houses in that location any more. As a “positional good”, their potential value knows no upper limit so long as buyers abound. Whereas the £2.50 cotton T-shirt in Primark (and I’ve bought a few of those of late) might tomorrow come from a distant source with even lower labour costs.

Meanwhile, insecurity drives the universal pursuit of a keen bargain. With median real incomes down by 8 per cent between 2007 and 2012, and modern afflictions such as zero-hours contracts now commonplace, a mist of uncertainty blankets the medium-term horizon for millions. The proletarianisation of many professional and so-called “creative” jobs means that the abyss lurks not far beneath even fashionable feet. For countless other families, the spectre of in-work poverty sits down at the table. In its latest report, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation found that 6.7 million out of 13 million people in Britain living in poverty come from working families – 4.5 million of those without dependent children. The queues at Aldi and Poundland will not shorten any time soon.

Just off Kilburn High Road, at a local church, the Trussell Trust runs one of its 350-plus food banks. Between April and December 2013, the trust’s banks delivered three-day emergency supplies to 613,960 people (221,468 of them children) in Britain, up from 129,670 in 2011-12. Although delays in benefit payments ranked as the largest reported cause of a request for help (31 per cent), the second most common motive for a referral was simply “low income” (19 per cent). Chris Mould, the trust’s executive chairman, tells me that “a significant number of people who come to food banks are in work”; that proportion “has risen quite steeply over the past three years”. Although sudden shocks, homelessness and benefit stoppages do still account for many visits, “there are many more people needing food banks because their income is inadequate”. And the nature of the trust’s referral system – via vouchers given by front-line professionals – may mean that its statistics underestimate the true scale of need. “There are more people out there in trouble than we see.”

On a sunny spring morning, Kilburn’s carnival of shopping still smacks more of hope than dread. But, you feel, it will always be a close-run thing. Here La Dolce Vita (a café) stands a couple of doors away from the Kilburn Pawnbrokers. The late Tony Benn once said that “people in debt become hopeless, and hopeless people don’t vote”. Pleasure and panic alike drives the thriving cult of rock-bottom retail. “Cheap and cheerful”? More like “cheap and fearful”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks