Andreas Whittam Smith: Capitalism does not have to be this greedy

The two important control mechanisms are active shareholders and perceptive regulators

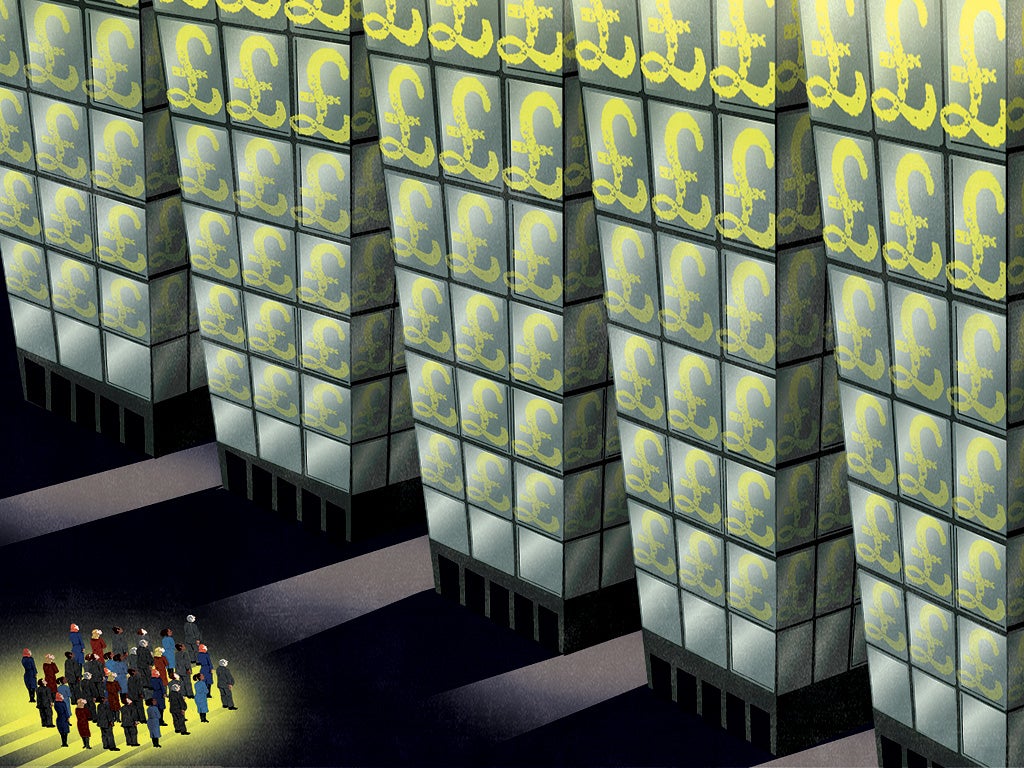

Capitalism is crisis" states one of the banners held aloft by protesters outside St Paul's Cathedral in London. This is correct. For capitalism will always go off the rails unless certain control mechanisms are in place. More threateningly, another banner warns: "Something better change". Yes, start the countdown. We really cannot go on like this. There is now an urgent need to rediscover and implement the checks and balances that allow the system to operate safely.

While "crisis" refers to the banking difficulties of two to three years ago, to the abrupt recession that has followed and to the present severe strains on Europe's single currency, there is more to it. The big underlying problem is the growing disparity between the income and capital of the top 10 per cent of people compared with the bottom 10 per cent. It is that, rather than the state of the economy, that is going to cause the most trouble.

It is a worldwide phenomenon. Some figures just published in the US reveal that between 1979 and 2007, the top fifth of the population saw a 10 percentage point increase in their share of after-tax income, that most of that growth went to the top 1 per cent of the population and that all other groups saw their shares decline by 2 to 3 percentage points. And in the UK last week, a report on directors' pay caused a clatter. For it showed that last year, directors of big companies enjoyed an incredible 49 per cent increase in their average pay that in turn gave them a colossal total reward of £2,697,664 per annum.

What interests me is whether the capitalist system can now start the process of self-correction. A beginning has been made in the sense that the problem is at last recognised. Commenting on the latest figures for directors' pay, David Cameron called for more boardroom responsibility. Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg called it a "slap in the face" for millions who were struggling. Moreover, the other day, at a round- table discussion, I asked a group of people managing very large sums of money for endowments, life assurance companies and pension funds, whether growing inequality mattered or not.

Remember that these executives, through their significant shareholdings in big companies, have the power to curb directors' pay. At all events, they unanimously agreed that wide income disparities mattered very much because they put the whole system in doubt. Perhaps a tipping point was approaching, said one. I wasn't expecting this unanimous expression of concern.

The two important control mechanisms that have been missing are active shareholders and perceptive regulators. The deficiencies of the regulators have, of course, been widely discussed; much less so the failings of shareholders.

In the 30 years from 1970 to 2000, large shareholders became passive. Few of them bothered to vote at company meetings, even fewer bothered to turn up in person. At best, a junior official would be sent. Directors of companies managed as they saw fit and paid themselves as much as they liked. However small were their own shareholdings, they began to act as if they were owners. Then around 10 years ago, this situation began to change. Institutional investors started to vote on the motions put before them.

Because of long years of disuse, their weapons had lost their cutting edge. In the case of directors' remuneration, for instance, where shareholders may express their opinion in an advisory capacity but have no legal right to insist, their impact has been small. And while shareholders must approve board appointments by casting their votes for the relevant proposal, they have nonetheless failed to secure men and women of genuinely independent minds to sit as non-executive members.

Shareholders' willingness to exercise their powers is extremely relevant to the discussion paper on executive remuneration that Vincent Cable, the Secretary of State for Business, published last month. This in turn is likely to lead to fresh legislation. There are two sorts of reform put up for consideration, soft and hard.

The soft options involve enhanced disclosure. The fact is, for instance, that exactly what individual directors are paid isn't crystal clear. The total remuneration of each director should be shown as a single cumulative figure. Moreover, companies make no disclosure of the pay bands of senior staff whose salaries may also be at stratospheric levels. In addition, the link between directors' pay and performance is often obscure and should be made clear.

Unfortunately one is entitled to doubt whether any amount of enhanced disclosure will make much difference in practice. This is the "living in a bubble" problem. In Lucy Prebble's play, Enron, one of the characters, referring to stock market bubbles, described it very well: "There's a strange thing goes on inside a bubble. It's hard to describe. People who are in it can't see outside of it, don't believe there is an outside." In other words, you cannot shame directors who pay themselves far too much by making them disclose all the gory details. Instead you have to put more power into the hands of shareholders.

Above all, you want measures that improve corporate governance. In this light, the much-discussed notion of levying a tax on all financial transactions, the so-called Tobin tax, is shown for what it is – a revenue raising device that won't change behaviour one jot. Another caveat is that strictly speaking, shareholders already possess a lot of power, even if they rarely choose to use it. In theory, for instance, they can call an extraordinary general meeting at any time and vote every director off the board and install new management.

However, there is one additional power that is worth considering. That is raising the status of the vote on directors' pay at annual general meetings from advisory to binding. At first glance, this additional power would be awkward to use. If a pay deal were voted down, what then? Wait a whole year until the next annual general meeting? No, this is not how matters would evolve. Directors would almost certainly get into the habit of negotiating with shareholders before making their proposals public. Both sides would have to up their game.

Of course the remedy for the widening gap between rich and poor isn't going to be found in a series of small measures like the above. Above all, it requires the powerful players to perform at the height of their responsibilities. Shareholders should be active, governments should be vigilant and the highly paid should break out of their bubbles and consider what damage their greed can cause. I can't say we are getting there, but perhaps we are making a start.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks