Robert Fisk: The Baghdad street of books that refuses to die

Saad Tahr Hussein rushes me through the narrow alleyway towards Mutanabbi Street, where the concrete wall in front of the central bank hems in the pedestrians. About a thousand Iraqis briefly see – or don't notice – the sly shade of a Brit as he stumbles down the alley. Then, in the square where the statue of old Marouf al-Rasafi, poet and history-debunker under British colonial rule, glares at the crowds, we turn left into the street of books.

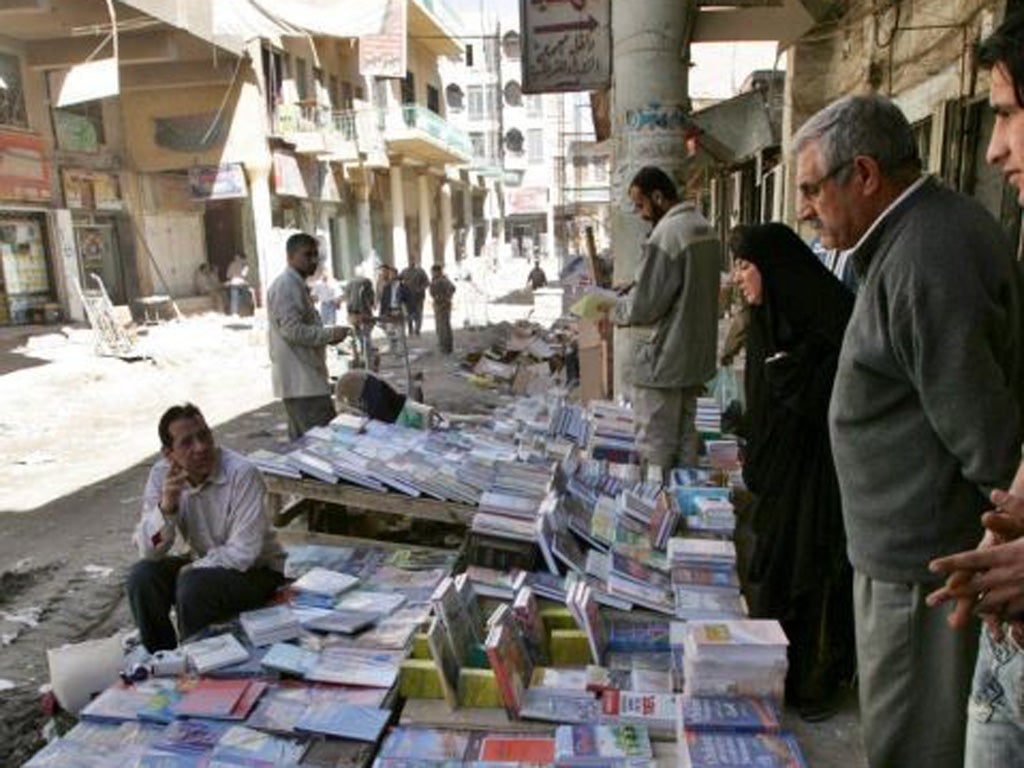

Everyone goes to Mutanabbi Street, its new statue of the Abbasid poet and king-praiser towering at the Tigris end. Here you get a feeling of what is going on in the mind of an educated Baghdadi, who still walks a road that you could get killed on five years ago.

There are chadored ladies and bare-headed girls and a bearded sayed with a black turban and a glorious green sash draped over his shoulders. There are pictures aplenty of Ali and Hussein – Iraq is, after all, a Shia country – and texts of religious jurisprudence and newly-bound Korans and, a reflection of the old Iraq, a mass of history books on Arab nationalism. They are all second-hand, laid out on cardboard on the pavement.

Last time I came here, there were no bare-headed girls, precious few divines. It's middle-aged men, secular, who bend over the history books. A young Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, confidant of Nasser, the doyen of Egyptian journalists (upon my word still alive, since he offered me a cigar in Cairo a year ago), smiles from a front cover. Many booksellers are communists.

A dour Edward Said (alas, all too dead) is printed across the Arabic edition of his essays on Palestinians. There is, unfortunately, that vicious old fake, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, on one pavement, a picture of Hitler and – very oddly – Rommel on the front. Several copies of Saddam's War, an unflattering portrait of the man who took his country to ruin in three massive conflicts, lay untouched on the ground. I point this out to Saad. "You have to know, Robert, that, yes, we hated him and the people of Samarra hated him for what he did to them and his city of Tikrit was just north of Samarra. But when the Americans came and the resistance began, the people of Samarra would shout Saddam's name – because he was the only nationalist figure left to them."

We arrive at the corner where the wall of the old Ottoman kulshah (roughly "cabinet") still stands, delicate stone insulted by a row of evil-smelling iron trash trolleys, the seat of the later royal cabinet as well, of the kingdom set up by Winston Churchill. Across the laneway, blessed in a fine, hot dust, is the crumbling wooden doorway of Dr Mohamed Abu Amjad's bookshop. Ashteroot books, medical, scientific, English literature, language, computers, history and arts, it says above the door. Mohamed, the bookseller who never closed during the years of darkness, rummages through his shelves. I immediately buy a rare first edition of General Muhammed Naguib's biography, the guy who overthrew King Farouk of Egypt and who was later outwitted by Nasser. I sit on a pile of books and prowl through its pages.

And I come across his description of British troops marching through the streets of Cairo during the Second World War. "Their troops marched through the streets of Cairo singing obscene songs about our king, a man whom few of us admired, but who, nevertheless, was as much of a national symbol as our flag. Farouk was never so popular as when he was being insulted in public by British troops, for we knew, as they knew, that by insulting our unfortunate king they were insulting the Egyptian people as a whole." And of course, I remember what Saad has just told me about the people of Samarra and Saddam.

I snap up a faded copy of Zaki Saleh's Mesopotamia 1600-1914 – published in Baghdad more than 55 years ago. Queen Elizabeth I sent the first Brit to Baghdad and Basra, and there are pages of head-chopping history as the sultans of Baghdad, variously loathed and adored by British consuls, meet their sticky ends. And there is a fascinating chapter on the relationship between British romanticism and financial speculation in Iraq, how the names of Babylon and the Tigris (Dijle in Arabic) bestowed a kind of respectability on Western acquisitiveness.

If ancient monuments showed that this was a rich land, a centre of civilisations, why could it not be a rich land again under Britain's guiding hand? Two Brits, Shepstone and Lee by name, published a monograph in Toronto in 1915 under the title "Future of Mesopotamia, how Bible lands may be restored to their former greatness as a result of the world war". Isn't that what our economic wizards told us in 2003, how Western know-how could restore Iraq's greatness?

We snap up a copy of Washington Irving's 1849 Life of Mahomet and Ilya Ehrenburg's The Fall of Paris, a forgotten 1942 novel of France's own occupation which at times reads weirdly like Irène Némirovsky's Suite Française. Then we speed away and, near the Tigris, Saad sees a street ad for the Gypsy singer Sajida Obeid and starts to bawl one of her more risqué chants. "Screwed are the men who drink only one kind of beer". They sing it at weddings. "Only one beer and you're not man enough," Saad explains. Funny what you learn on the way back from the street of books.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies